Poincaré's medical leave delayed the necessity of deciding on his future at Interpol. The damage to his hand had been considerable and the surgery, extensive. His main business at the farmhouse was to heal and, for a few months, forget about algorithms and the Soldiers of Rapture—who, in their disappointment, had stopped murdering innocents just as the profilers had predicted. Even they, with their tortured logic, allowed that murder had not hastened His arrival. For the most part talk of the End Times receded and, with it, the appearance of robed prophets calling on sinners to get right with the Lord. As if a switch had flipped, the psychopaths who set bombs for Christ found other outlets for their demons. Gradually, a more predictable mayhem took hold.

Summer yielded to autumn rains that prepared the fields for another year's bounty, and Poincaré tended his wife with patience and a gentle hand. He fed and bathed her. He smoothed her hair and, daily, invited her return. And though Claire continued to say nothing and for many more weeks closed her eyes to him, she did return.

It happened this way.

Poincaré's finances were in ruins. Etienne and his family were well enough to resume their lives in Paris, but the hospital bills generated by their prolonged care in a private clinic and the continuing fees of consulting physicians had wiped clean Poincaré's savings and virtually all his equity in the farm. On a Tuesday in mid-October, he traveled to Lyon to visit with his banker and renegotiate the mortgage, again.

"You have no case to make," said the woman reviewing the papers.

"I have my good name," he answered.

"Monsieur, we're looking for more tangible collateral."

"Of course. How about this?" He had taken up Serge's habit of spinning that monstrosity of a silver ring in times of stress. The lung cancer had finally claimed Laurent, who got his wish and died in one piece—albeit a considerably diminished piece—buried beside his first wife on a hillside in Bordeaux. He willed Poincaré the ring along with a considerable wine cellar as a grand, final joke. In honor of Serge, Poincaré met the banker head-on. "Reduce the loan-to-equity ratio to three percent," he said. "You'll own ninety-seven percent of a prosperous vineyard. You know, the almanacs are predicting an excellent vintage next year. And apparently, having let my crop rot on the vine this season prepares the soil for an excellent harvest in the future."

"We deal in present value, Monsieur Poincaré. We don't want your wine."

Doesn't anyone?

he wondered. "Alright, then. Let's refinance to five percent, and I'll figure something out."

There was not much to figure. He had only his salary left from a job he might quit. The bank president, a former neighbor in Lyon, asked that he step into his office: "Henri," he said, "we can refinance a final time—to six percent equity at market rates for forty years. But if you default again, we'll sell the property. You're a good soul and your difficulties have been, well, epic. But there are limits to—"

"I appreciate your position," he said, rising to excuse himself. "Please draw up the papers."

After a long and uncomfortable return trip to Fonroque, his arm still in a sling, he turned up the gravel drive to the farmhouse and saw smoke rising from the chimney. A car was parked in the drive, and he did not recognize the plates. He walked to the front door, ajar slightly—which annoyed him because heating costs had soared of late, and he had made a point of conserving. But then, through the open door, he heard a sound that lifted him just as surely as Ludovici's bullet in Dam Square had laid him down. Laughter. He nudged the door open and saw Georges and Émile dodging before a blindfolded Claire. Georges ran and spun, and while Poincaré could plainly see the child wore a prosthetic leg, it did not seem to slow him or otherwise reduce his pleasure at grazing Claire's skirts and pushing his brother forward.

"You go this time," he said to Émile.

"No! It's y

our

turn." At both ears, Émile wore hearing aids.

So Georges edged toward his grandmother, blindfolded as in their old game, and Poincaré watched as she extended her fingers to feel the child's face. She pulled him onto her lap and kissed his cheeks and then inhaled the scent of him. "Ah," she said. "You are delicious, Monsieur Strawberry! I require two hugs and a kiss on the tip of my nose."

Georges squealed: "I'm your

cream

, Mamie! Émile's your straw- berries!"

Claire removed her blindfold and pulled the children close. Notwithstanding their months in the hospital, the boys had grown. Both angled onto a lap that was now too small to accommodate a pair of healthy seven-year-olds. Poincaré pushed the door further ajar, and when she noticed the movement and saw him across the room, actually saw her husband for the first time in a half-year, Poincaré prayed she would accept the penitent standing before her. No words passed between them. The clock on the mantle ticked. Ticked. Ticked. To the children she said: "Émile, Georges. I feel a draft. Please close the door."

They turned and they were on him.

"My hand, watch my hand!" he cried as the young life tumbled over Poincaré to shouts of P

api

! P

api!

Stipo Banović, convicted of crimes against humanity, managed to hang himself in his cell the morning after his verdict was read, despite a suicide watch. Felix Robinson called with the news. "Finally, this business with Banović is over, Henri." And so it was. If Poincaré faced threats again in his life, they would not come from this man who, so brutalized, had himself turned brute. When Poincaré heard what had happened, he turned in silence to his own family, occupied with the little motions that constitute a life: Claire was finishing

Les

Miserables

; Etienne, who had approached him one day and said I'

ll

try . . . if you help

, was building a moon colony with the boys, using every pot in the kitchen; Lucille was practicing her viola. Peaceful days passed. Late one afternoon, he was sorting mail and opened a letter postmarked Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Henri,

I hope this finds you well. I have received new correspondence from Madeleine Rainier—who, I am relieved to learn, is no longer a fugitive from justice. Miss Rainier has come into some money, quite a lot. She has opened an unrestricted account in your name at the Bank of Geneva with 12 million euros. French taxes have been paid on the original amount of 19 million, so the money is yours

in

toto

. She asked that I send along the paperwork and relay the following message: "One buffalo nickel, redeemed in full. Thank you, MR—and, by the way, my father sends his regards."

I look forward to our correspondence, Henri.

Yours sincerely,

Peter Roy

Life

, thought Poincaré,

is so very strange

. He neither jumped for joy nor called Claire into the room to pronounce their money troubles over. She knew nothing of them in any event, having only just returned from a fearful journey. Poincaré reread the letter and walked to the terrace, where he looked across the vineyards to the hills winking in the sunset. He thought of Banović and of a ravine in Bosnia; he thought of Eduardo Quito and of a man who drank whiskey for breakfast, mourning a wife dead and a daughter lost; he thought of these rolling hills, of grape arbors and trees in winter and of the cold, cobalt sky; and he thought of Claire, when she finally spoke his name. Each its own, each a facet of the jewel James Fenster had discovered but kept, with good reason, from an undeserving world. It was enough for Poincaré to acknowledge that at every instant he no less than the mighty oak on this terrace was branching and reaching. He returned to the house, to his desk, and wrote two letters, the first to a physician in Boston:

My dear Dr. Beck,

After careful consideration, I have elected not to have the surgery you recommended. My heart, such as it is, will have to do. Thank you for wise counsel just the same.

Yours,

Henri Poincaré

The second letter he addressed to Peter Roy.

My friend,

You have delivered extraordinary news. There is much to discuss, and perhaps we'll do so soon, in person. But foremost in my mind is this: I ask that you establish and become administrator of a Trust account for the benefit of a certain widow and her two children. I enclose their present address in The Hague and ask that my name never be associated with their care. The widow is to receive a monthly stipend of 8,000 euros for her family's maintenance. All expenses for the education of her children through to university are to be paid directly by the Trust, with application made to you or to your agent in The Hague. Payment of her monthly stipend is to continue throughout her life. Thank you in advance for discretion.

Yours,

HP

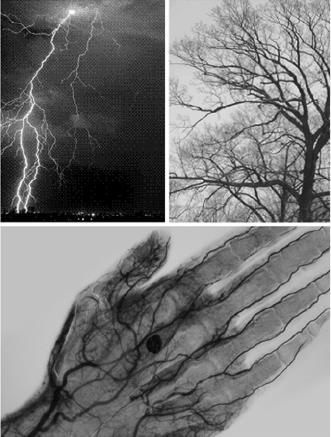

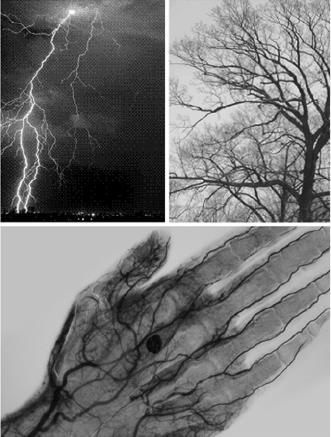

He sealed the envelopes and set them on the corner of the table. Hearing a first call to dinner, he squared the blotter on his desk and dusted a picture frame, which held three images: two, from Fenster's apartment, via the collection Jorge Silva had managed to save; one that his doctor had presented after surgery.

Poincaré would have preferred straight lines. He would have chosen love without loss and goodness without pain. But then no one asked for his opinion when the foundations of the earth were laid. What Jules Henri had glimpsed and Fenster proved settled everything and nothing in ways that moved him to tremble at the sweep of wind through tall grass and the cry of a child in the night for his sister. For he, too, had seen the Aurora, both above and below; and he, too, had named the dance from which this world springs into being at every instant. He once thought retirement would bring an end to the words

why

and

who

and

where

—words that had served him well over a long career. But this could never be. Indeed, his investigations had just begun.

Henri Poincaré rose and adjusted his sling. His hand ached, and he knew that the strength he was regaining would not restore the strength he once had. He thought of Chloe and choked back a sob. From the kitchen, laughter rose like music through a house of mourning, breaking a spell that had settled for too, too long.

Etienne leaned into the room. "Papa, dinner."

"Yes," said the father to his boy.

Poincaré closed his eyes; when he opened them, Etienne was still there.

CREDITS

TEXT

Opening epigraph. Rami Shapiro, translation of Psalm 29. Used by

permission.

Parts I–IV epigraphs. Job 38: 17, 19, 25, 36. NIV. Matthew 24:24,

Revelation 14: 6–11, Isaiah 65: 21–24: Scripture taken from the

HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, as presented

on biblegateway.com. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 Biblica. Used

by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved. The "NIV" and "New

International Version" trademarks are registered in the United States

Patent and Trademark Office by Biblica.

Afterword epigraph. W. H. Auden, Preface to "The Sea and the Mirror." In

Collected Poems. New York: Modern Library-Random House, 2007. 403. Mark 13: 24–27. Scripture taken from the NEW AMERICAN

STANDARD BIBLE®, as presented on biblegateway.com. Copyright

© 1960,1962,1963,1968,1971,1972,1973,1975,1977,1995 by The

Lockman Foundation. Used by permission.

1 Corinthians 15: 51–53, Acts 2:38, John 15:7, John 8:31. Scripture

taken from the New King James Version, Bible, as presented on

biblegateway.com. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Hotel Paris (Las Vegas). "A convergence of elegance and energy . . ." Online

ad copy.

Jules Henri Poincaré. "Mathematics is the art . . ." The Future of

Mathematics.

Text on ammonium perchlorate and explosives. By Graham Orr. Used by

permission.

Thornton Wilder. "Money is like manure . . ." The Matchmaker: A Farce in

Four Acts.

IMAGES

Lightning, negative image. © Stasys Eidiejus - Fotolia.com

Epitaxial growth. Image courtesy of F. Gutheim, H. Müller-Krumbhaar,

E. Brener; IFF, Forschungszentrum Jülich, Germany.

Christchurch, New Zealand. NASA. "Image of the Day Gallery."

http://www.nasa.gov/multimedia/imagegallery/image_feature_678.html Bacterial growth, Petri dish. Fig 1(d) in the paper "Cooperative strategies in

formation of complex bacterial patterns," by E. Ben-Jacob, O. Shochet,

I. Cohen, A. Tenenbaum, A. Cziruk, and T. Vicsek, in the journal

Fractals, 3 (1995), 849–868.