All the King's Cooks (20 page)

Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

When the King had entered the Presence Chamber, attended by the Lord Chamberlain, and taken his seat at his table beneath the ‘canopy of estate’, everyone not directly involved in serving the meal, including the Lord Chamberlain, would leave the room.

16

Now the carver began his highly accomplished work. He had to know the particular way of carving each dish, how to cut it into pieces and place it on the King’s trencher, and how to serve it with the appropriate sauces or other accompaniments. Using a carving set such as the ‘case of lether with thre karvvnge knives and a forke and viii meate knives thaftes [the hafts] white and grene garnished with metalle guilte’ – one of thirty such sets owned by Henry VIII – the carver would take a knife, holding it between the thumb and first two fingers of his right hand. Then, being careful to use the correct terms and procedures when tackling each dish, he would carry out the specific operations, some of which are listed here:

17

Meat | Carving term | Action and sauce |

Brawn | leche | Slice, lay on a trencher, serve with mustard. |

Venison | break | Slice, 12 cuts across with edge of knife, put in frumenty. |

Pheasant | alay | Lift with left hand, remove wings, mince the meat into a syrup. |

Goose | rear | Cut off legs, then wings, put legs at each side of separate platter, carve meat from the carcase, put it between legs and wings in the platter. |

Hen | spoil | Cut off legs, then wings, mince wings, sprinkle with wine or ale ‘for the sovereign’. |

Hot pies | Remove lid. | |

Cold pies | Cut off crust from half-way up the sides. | |

Salmon | chyne | Slice into a dish, serve with mustard. |

Haddock and cod | side | Cut down the back, remove bones, clean inside. |

Baked herrings | Serve whole with salt and wine. | |

Salt fish | Remove bones and skin, serve with mustard. | |

Custard | Cut into 1 inch (2.5cm) squares. |

The carver also undertook a little cooking at the table, using chafing dishes of silver gilt. Partridges, for example, had their legs and wings cut off and the flesh warmed with wine, ginger and salt in a dish set over glowing charcoal.

18

Other chafing dishes were ‘gilt with hooles to roste Egges in, thandles and Feete of brasil, the chafingdishe foure squared having at everie corner a gilt pillor poiz [weighing] with the Brasil LXVII oz (1.9kg).

19

Served in this way, all the King’s food appeared at his trencher ready for eating with the thumb and forefingers of his right hand, or, if soft or semi-liquid, his spoon. At his side he would find a manchet cut into fingers for eating with the other foods.

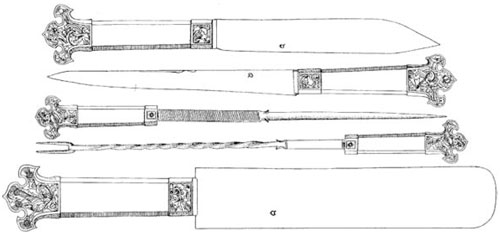

39.

A Carving Set

Henry VIII owned numerous carving sets, most of them housed in black leather cases. They may have resembled this German set of the late fifteenth century, which includes (top to bottom): a broad and a narrow carving knife, a sharpening steel, a serving fork, and a broad-bladed knife used either for serving or to scrape up crumbs from the tablecloth when ‘voiding’, or both.

As for drink, the sergeant of the cellar, with his yeoman of the King’s mouth, served wine and ale to the King’s ‘cupboard’ after it had been brought up by the groom of the cellar to the King’s mouth.

20

The cupboard – literally a ‘cup-board’ or table – looked very impressive with its display of vessels beautifully worked in gold, silver gilt and other precious materials. Wine would be placed here in matching pairs of flagons like those – ‘well-chased, their bailes [handles] being Dolphyns fastened to the backes of a man and a woman, sitting upon the Baile a man holding in his hande a Cluster of grapes weying togethers DLXIIII oz [15 kg]’.

21

Here too were the cups made of gold, silver gilt, mother of pearl, ostrich eggs or porcelain; some were made for specific purposes, such as the gold malmsey cups, the beer cups of alabaster, serpentine or silver and gilt, and the assay cups used by the officers

of the chamber to taste samples of water for washing or drink for the King’s table before it was served by the cupbearers.

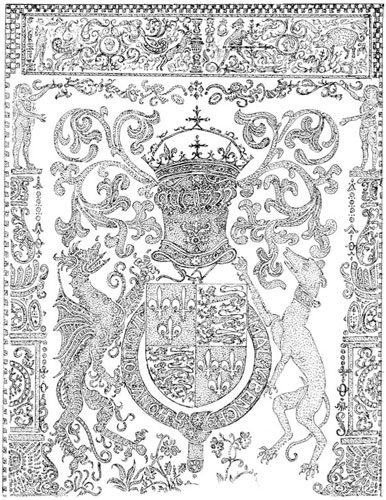

40.

A Tudor napkin

The arms woven in the damask of this fine linen napkin are those used by both Henry VII and Henry VIII. The combined hunting- and food-based themes of the top panels, which show a huntsman blowing his horn, a hound and a deer, and a hunter with his spear approaching a boar, would certainly have appealed to Henry VIII.

Once the main courses had been served, any food or drink remaining on the table after the King had finished was ‘saved and gathered by the officers of the almonry, and from day to day to be given to poore people at the utter court gate, by oversight of the under almoner, without diminishing, embesselling, or purloyning any part thereof, and neither in the chamber, nor other place where allowance of meate is had, the meate to be given away by anny sitting or wayting there’.

22

Tempting as they were, all these dishes from the King’s table were to be given to the poor, the staff of the privy and presence chambers being provided with their own separate meals after the King had dined. One of the King’s alms dishes, presumably for table service, was made of 314 ounces (8.9kg) of silver gilt, ‘like a shippe, having two plain plates uppon the sides wherein the kinges armes is set’.

23

For state occasions it was borne by the Great Almoner, Dr Nicholas Heath, Bishop of Rochester, but at other times by John Batt, the under-almoner. Along with all the other food left over from the Council and Great Watching Chambers and the Great Hall, it would be carried down to the almonry (no. 55), close to the hall-place dresser, ready for distribution. Towards the end of the meal, probably after the second course, digestive dishes such as roast apples with caraway comfits, or cheese, were served, and then the remaining bread, napkins and tableware cleared away with due ceremonies. The carver next gathered together the crumbs and any scraps left on the cloth, using a broad-bladed ‘voiding knife’ and a shallow narrow-rimmed dish called a voider.

24

Now the King would stand up, an usher kneeling before him to clean any crumbs form the skirts of his coat. It was at this point that the ‘void’ was served with the wafers brought here from the wafery, the hippocras prepared in the privy cellar, and all the spice dishes laden with comfits and dry and wet suckets prepared in the confectionary. It was for the latter that the King would use a fork, an implement used solely for eating ginger and similar preserves in syrup; it was not until the following century that the fork began to replace the fingers for eating meat and other foods. Henry VIII’s inventory of 1547 lists both ginger forks

and combined implements with ‘one spone with suckett forke at thende of silver and gilt poiz one oz iii quarters [45g]’.

25

A sewer and a gentleman usher now brought a linen surnap and a towel from the ewery table, these having been carefully folded together in the form of a rectangular concertina. The surnap, as the name suggests, was designed to cover the napery, and was simply a long white linen cloth; the towel was another long piece of linen damask, worked with lovers’ knots or fleur-de-lis and measuring some twenty-seven inches (68.5cm) wide.

26

Placing these on the table end to the King’s right, the usher would put his rod inside the surnap and towel and walk down the front of the table, drawing them out across the tablecloth and reverencing the King when he was directly before him; then he would proceed a few feet beyond the far end of the table and kneel there, while supporting his end of the surnap and towel. Back at his end of the table, the sewer now knelt and firmly gripped his end of the surnap and towel, so that the usher could stretch them taut and fold the overhanging end up on to the table. Then he would rise, walk before the King to his right side, and slip his rod beneath the surnap and towel to form a single loose pleat called an estate. Passing before the King with a further reverence, he made a similar estate to the King’s left before returning to his end of the table, kneeling and straightening the towel once more. Having completed these duties, he again carried his rod before the King, reverenced him, and returned to his place. Now the nobles bearing the ewer and basin approached, so that the King could wash his hands and dry them on the towel. To complete this whole ceremony, the usher slipped his rod into the folded towel and surnap at his end and pulled them along towards the King, while the sewer brought up his end at the same time so that towel and surnap were gathered together for the sewer to take back to the ewery table.

27

Finally, the dining table itself was dismantled and taken away, leaving the King standing beneath his canopy of estate ready to resume his activities.

This sketch of Henry VIII at table – which would apply to the Queen too – lacks many details, especially when compared with late fifteenth and early sixteenth century descriptions of noble and archbishoply dining ceremonies that set out every movement of

the servants and tableware, but it does give some impression of the formality and magnificence of Tudor royal dining habits.

Even when the King dined away from the Presence Chamber his table there was still served with the King’s service, but it was now the Lord Chamberlain who ate there, with lords spiritual and temporal above the level of baron – barons were admitted only if insufficient numbers of higher nobility were present at court.

28

Dining in Chamber and Hall

Etiquette and Ritual

The Lord Great Master, with a number of other lords, dined in the King’s Council Chamber, where they were attended by two of his gentlemen, a gentleman usher, a sewer, the hamperman, and grooms and pages of the chamber, with one yeoman usher to guard his door and another to bring up the food from the Lord’s-side dressers. All these servants ate the food left after the nobles had dined at 10 a.m. and taken their supper four hours later.

1

The Lord Chamberlain, meanwhile – unless dining in the Presence Chamber – took his meals in the Great Watching Chamber with other lords and ladies, the Vice-Chamberlain and the Captain of the Guard, as well as the King’s cupbearers, carvers and sewers, esquires for the body, gentleman ushers and sewers of the chamber who were not on duty that day. Here they were served by a gentleman usher, a sewer, a groom and pages of the chamber, a yeoman of the chamber to bring up the food from the Lord’s-side dresser, and an usher to guard the door. All of these later dined on the food left after the senior officers had departed.

2

In the Great Watching Chamber and the other, smaller, chambers where specified officers such as the Master of the Horse, the Captain of the Gentlemen Pensioners, the Secretaries and the servants of the King’s and Queen’s Privy Chambers took their meals, there would be far less ceremony. Serving and eating habits here

were probably just like those to be found every day in any noble dining chamber. Good table manners would be

de rigueur

, especially since everyone dining here would have been sent away from home when quite young to be a servant in a household of equal or superior status to his own, in order to gain those polite accomplishments which would elevate him from the lower orders for the rest of his days.

When meals were to be served in the Great Watching Chamber, the tables would be set up by the pages, who may have stored them in their adjacent pages’ chamber when not in use.