All the King's Cooks (15 page)

Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

At Hampton Court and at the other royal residences three different qualities and ranges of food had to be prepared for three different groups of people, and so the kitchens were divided into three separate units. The hall-place kitchen cooked for the minor courtiers and household servants who dined in the main body of the Great Hall; the Lord's-side kitchen cooked for the nobles and senior household servants who dined on the dais in the Great Hall, in the Council Chamber, in the Great Watching Chamber or in their own offices; and the Privy Kitchen cooked for the King and Queen. This arrangement ensured the maximum efficiency, enabling the clerk of the kitchen to allocate food from the larders to the appropriate kitchen, where the sergeant, yeoman and groom cooks, the scullions and turn-broaches, could develop their distinctive recipes and expertise.

The hall-place kitchen (no. 39), the first kitchen you come to at the end of the Paved Passage, occupies part of the site of Wolsey's hall-place

kitchen-workhouse â its eastern end and the eastern half of the south wall survive from this building. The remainder was demolished and rebuilt in a greatly extended form for Henry VIII in 1529â31, to create a massive rectangular kitchen measuring almost fifty feet (15m) by thirty feet (9m), with walls twenty-three feet (7m) high to the eaves. This room was certainly not designed for delicate cookery; it was, in essence, a great boiling and roasting kitchen, ideally suited for mass catering on the largest scale. Its huge capacity is clearly demonstrated by the size of the great fireplaces. There are three of them, each some eighteen feet (5.5m) wide, six feet (1.8m) deep, and seven feet (2.1m) high. Their broad Tudor arches, cut from great blocks of stone, are quite narrow from front to back so as to help prevent the escape of smoke, but the brickwork above is considerably thicker and incorporates relieving arches which transfer the great weight of the chimney-stacks away from the masonry arches down to the sturdy side walls. Unlike most Georgian and later kitchen fireplaces â which, since they were designed to produce mainly radiant heat for roasting, were much shallower â those at Hampton Court are very deep. Their six-foot (1.8m) depth was necessary to create the very large working hearth area, in total some 324 square feet (30 square metres) in this kitchen alone, on which a number of separate fires and cooking processes could be in operation simultaneously. Quite different from later cooking methods, it was none the less a very flexible and practical system.

All the fireplaces burned wood in the form of large logs or talshides. Manoeuvring tons of this heavy, bulky material in through the Back Gate, through the Boiling House and along the Paved Passage would have been an extremely awkward business, bringing unwelcome dirt, labourers and congestion into an already bustling environment. For this reason, a wide archway had been built in the orchard wall at the north side of the Back Gate, and similar ones in the eastern end of the north wall and in the centre of the west well of the adjacent Lord's-side kitchen, so as to provide a convenient direct route to the fireplaces from the woodyard in the Outer Court. These archways also served another important purpose. Fires need both fuel and a good supply of fresh air, if they are to burn efficiently. Once the brick-

work of the huge chimney-stacks had warmed up, they drew up vast quantities of hot air and smoke from the logs flaming on the hearths below, thoroughly ventilating the kitchen with their strong draught. In summertime this greatly improved the working conditions. But in winter, when the kitchens were almost permanently in the shadow of the Great Hall, it turned these rooms into the iciest of wind-tunnels. Frost and dustings of snow would remain unmelted for days on the window-ledges and pointing of their north façade, and inside, despite the roaring fires, the cooks may well have worked for days at a time in subzero temperatures. This was vividly brought home to me over Christmas and New Year of 1996â7, when the weather was so cold that the Thames froze over. While I was working here one clear, cloudless day, flurries of snow began to fall across the kitchen tables and floor. But these had not been blown in through the roof, which is completely weathertight â they were formed when the water vapour rising from the cooking pots simmering on the stoves froze in the chill air of the roofspace above and then descended as snowflakes!

To carry out cooking operations within the Hampton Court kitchen fireplaces, the cooks must have had access to a substantial

batterie de cuisine

. No contemporary descriptions survive, but it is probable that the original pieces of equipment, along with various replacements, were included in the parliamentary survey of the kitchen undertaken in 1659. Copper and brass cooking pots can enjoy a very long working life; some pieces acquired by certain country houses in the 1820s were still in use up to the 1940s, for example, while one down-hearth frying pan removed from the kitchens of Cowdray House in Sussex in 1793 was apparently used by a local family before being returned, still in good condition, some 150 years later. The 1659 inventory includes:

For boiling | 1 copper to boil meat in, covered with lead (this would be the built-in copper in the Lord's-side kitchen boiling house) 6 very large copper pots, tinned 2 smaller ones, tinned 5 brass kettles with iron feet, tinned |

( | 2 great copper cans to boil fish in |

1 large long copper with a false bottom to | |

boil fish in | |

5 large brass pieces with holes in them to | |

take fish out of the pans | |

( | 4 pudding pans |

( | 6 storing pans of copper, tinned |

( | 3 iron trivets |

3 brass scummers and a brass ladle | |

For roasting | 9 spits |

1 pair of large iron racks (presumably those still there) | |

4 large iron dripping pans | |

For broiling | 2 very large gridirons |

For frying | 3 great frying pans |

Miscellaneous | 11 flat brass dishes, tinned over |

18 wooden trays | |

5 cleavers or chopping knives |

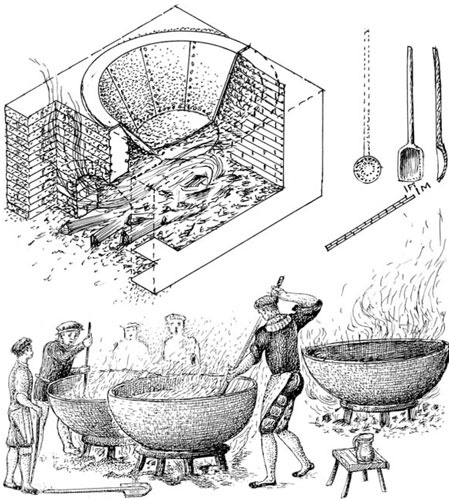

Some of these items would have been used in the hall-place kitchen, where a fairly limited range of foods was cooked â mainly boiled, probably â beef, mutton, lamb, veal, coney and goose on meat days, and ling, plaice, whiting and other âsea-fish' on fish days. From contemporary illustrations and excavated examples we can gain a good impression of the appearance and construction of the tinned copper pots: their bases raised from thick sheet metal, their sides extended with riveted plates, and their rims wire-edged around thick wrought-iron hoops, with stout suspension rings at each side. They would have been filled with meat, water and seasonings, and then placed on iron trivets in the fireplaces. A full boiling pot might easily have weighed a half of a ton (500kg) or even considerably more. Those recovered from Henry VIII's flagship the

Mary Rose

had capacities of 140 and 80 gallons, capable of cooking some 1300lb (590kg) and 900lb (410kg) of food respectively. A number of similar vessels in Hampton Court's kitchen would have enabled the cooks to simmer the meat and fish, and boil the vegetables required to serve all those dining in the Great Hall.

26.

â

Cauldrons

Tudor cauldrons as found on the Mary Rose (top) and as seen in the painting of

The Field of the Cloth of Gold

(bottom)

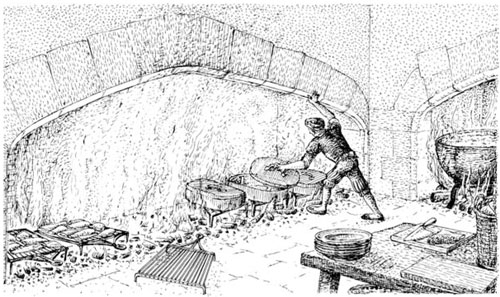

The other large-scale method of cooking fish was to broil it, placing it on a very large gridiron supported a few inches above a level mass of glowing embers. Gridirons of this type are to be seen hanging against the wall in A. Pugin's early-nineteenth-century view of the kitchens of Christ Church, Oxford: each gridiron being some three feet (90cm) square, with parallel rows of iron bars on which to place the fish. The same view shows a huge square gridiron mounted on low wheels on which meat and fish could be grilled over a bed of embers. Most fish, except salmon or eel, were also fried in unsalted or clarified butter, or olive oil, after being dipped into milk and then floured (or just floured), before being placed into the hot fat. Fresh parsley was fried in the

same pan immediately after the fish had been removed, and then laid over it ready for serving.

9

Roasting was primarily a method reserved for cooking the more tender joints of meat, along with poultry and game. Today the word âroast' is almost always used to mean baked. It might seem unnecessary to differentiate between these two words, but they are in fact distinct methods of cookery, and produce quite different results. When a joint is âroasted' in the modern sense in an oven, it is enclosed within a small volume of static, or virtually static air, and sits in a tin of boiling fat and juices which frequently scorch to blackness around the sides. The whole atmosphere inside the oven becomes heavy and fat-laden, carrying the odour of the overcooked fats, which may then permeate the meat, giving it a fairly heavy flavour. Real roasting, in contrast, relies solely on a fierce radiant heat: the meat is mounted on a spit where it remains constantly suspended in a stream of fresh air that carries off all unwanted smells and leaves any excess fats free to drop away, thus rendering the meat light and flavoursome.

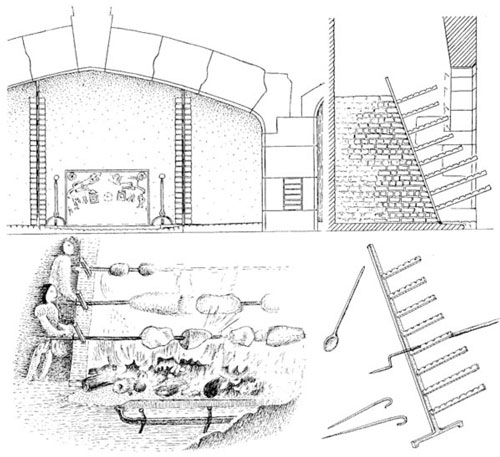

27.

â

Cooking fish

Most of the fish required for dinners and suppers every Friday and Saturday was broiled over glowing embers on large gridirons, or simmered in herb-flavoured stock in fish kettles.

28.

â

Roasting

The great racks or cob-irons in the Lord's-side kitchen fireplace probably date from around 1530; they were set up exactly as shown in the painting of

The Field of the Cloth of Gold

, and were also recorded at Hampton Court in the seventeenth century. Note the dripping pan which caught the juices, the skewers used for trussing and the spoon for basting the meat.