All the King's Cooks (6 page)

Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

Using money advanced to them by the clerk for the coming month, the Hampton Court purveyors would purchase their poultry as required. In the case of shortages, they could compulsorily requisition supplies from members of the Poulterers’ Company of London, paying the agreed prices. The Company was also obliged to buy back at the same rates any supplies that the palace purveyors found they didn’t need. In return for these impositions, it was agreed that the purveyors would not take any poultry from within seven miles of London, and that they would not purchase any birds offered to them by nobles or gentlemen.

20

Most of the poultry was probably unloaded in the poultry yard so as to be ready for preparation before five in the morning.

21

The sergeant then checked it for quality and quantity.

22

If it contained any bad stuff, he rejected it and reported the purveyor to the clerks of the greencloth for punishment, while if it was of overall poor quality he could call in the clerks comptroller, who would reduce the price accordingly. As soon as it was accepted, the poultry was carried into the scalding house, where great pans of water would already be boiling over the fires. If the birds were dipped in for half a minute, the feathers could easily be plucked out by pulling them against the grain.

23

Since this process heated the carcases, it could make them go off within a day. Long experience

had made this common knowledge, so the birds were plucked immediately before being cooked; those for late-morning dinner were delivered fresh to the larder by 8 a.m., and those for early-evening supper by 3 p.m. They were probably delivered drawn, but with their heads and feet in place to make it easier to tie them on to the spit, and with their major organs still inside for use by the cooks in specific recipes.

To the east of the Poultry, in the centre of the outer offices, lay the bakehouse.

24

At Hampton Court at this time the sergeant of the bakehouse was John Heath. He it was who had provided all the ‘hard tack’ biscuits for the King’s siege of Boulogne in July 1544, and personally served there as a standard-bearer in the army, for which he earned an additional two shillings a day. Assisted by his clerk, he supervised the provision of all the bread required for the court.

25

The supplies of wheat were either purchased from outside or brought in from the royal estates by two yeomen purveyors, each load being delivered by cart or by barge and then measured by the bushel (64 pints, 36 litres); the sergeant or his clerk would always ensure that all of it was sweet and good for baking.

26

Some of the six ‘conducts’ (labourers) would carry it up the two broad staircases from the yard into the granaries, where the yeoman garnetor cleaned it and turned it, as necessary, to prevent it being spoiled by mildew or pests. This officer was also responsible for sending the wheat to be ground at the mills; he would make sure to check that the same weight that went out as grain returned as meal, for the King never surrendered a percentage of the meal as toll, but paid for the miller’s services in cash.

On its return, the meal was boulted, or sieved, by the labourers. A coarse sieve first removed the bran, which the sergeant sold to the avener for feeding the King’s horses. The remaining meal was either used to make ‘cheat’, or wheatmeal bread, or put through a very fine sieve to produce an almost white ‘mayne’ flour for making small loaves of the highest quality, called manchets. For general use the yeoman fernour (a baker in charge of the ovens or furnaces) would season the flour, prepare the leaven or yeast, make sure the dough was not too wet, check its

weight in his balance both before and after baking, and heat the ovens in the great bakehouse. John Wynkell, the yeoman baker for the King’s mouth, made the ‘mayne, chete and payne de [bread of] mayne’ for the royal table quite separately in the privy bakehouse. In 1546 the King had granted him the additional office of bailiff and collector of revenues for the lands of dissolved Leicester Abbey, in both Leicestershire and Derbyshire.

27

The bulk of the Bakehouse’s production was the cheat bread, the wholemeal loaves that in 1472 are recorded as weighing about 1lb 9oz (725g) each.

28

Around 200 or more messes of cheat were required every day to serve with meals, along with a minimum of 150 additional loaves to provide the breakfast, afternoon and supper-time snacks for those who had bouche of court. Similarly, over 700 manchets were required for the upper household’s meals, and further supplies for bouche-of-court staff.

To make the cheat bread, the wholewheat flour was tipped into a deep wooden dough trough, and a hole scooped in the middle. Into this was poured a solution of old sourdough mixed with lukewarm water; next, it was mixed until it thickened enough to resemble pancake batter, as Gervase Markham tells us in his

The English Hus-wife

of 1615.

29

The batter was then covered with more meal and left to ferment overnight to form a spongy mass. In the morning, the remaining meal was kneaded in with a little warm water, yeast and salt to form a dough. Kneading by hand was far too laborious and slow for operations of this scale, and so it would either have been worked beneath a ‘brake’, a long beam secured to a bench by means of a strong iron shackle, or folded into a large clean cloth and trodden under foot. It is possible that the canvas ‘couch cloths’ (table cloths) purchased for the Bakehouse in the 1540s were used for this purpose.

30

Having been left to rise for a while the dough was then divided into individual loaves, which were weighed, worked or moulded into shape, and left to rise once more, ready for baking in the ovens.

To make manchet bread, fine boulted white flour would be similarly tipped into the dough trough and have a hollow scooped out of it, but instead of sourdough, a barm or liquid aleyeast would be poured in – the sergeant purchasing this as required.

31

Having been mixed with salt and warm water, it was kneaded up on the brake or under foot, allowed to rise, then

kneaded once more and divided up into individual loaves or rolls. Once each loaf had been weighed and shaped into a smooth ball, it was lightly rotated with the left hand while a knife in the right would slash it all the way round. A stick or a finger was then used to poke a dimple into it from top to bottom. This preparation gave the manchets their characteristic shape and quality. With the sides of the loaf slashed, the dough was free to rise upwards, giving a lighter, taller end product, much better for table use and also occupying less of the valuable oven space. The dimple, meanwhile, prevented the fermentation gases from forming unwelcome bubbles under the upper crust.

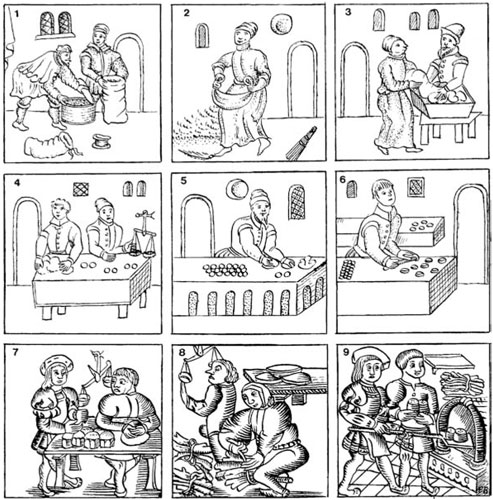

4.

Tudor breadmaking

These drawings based on the 1596 ordinances of the York Bakers’ Company and on a mid sixteenth century assize of bread (bottom row) show the processes which the bakers and their labourers would have carried out here:

1.

Measuring the wheat on its arrival, using a bushel measure and a ‘strike’ to level its surface.

2.

Boulting the ground meal through a piece of canvas to remove the bran. Note the goose-wing and the brush for sweeping up the flour.

3.

Mixing the dough in a trough.

4.

Weighing manchet dough.

5.

Moulding manchet loaves.

6.

Cutting the manchets around the sides with a knife.

7.

Moulding cheat loaves.

8.

Tying up faggots for the oven. This labourer is wearing a linen coif, a close-fitting cap tied beneath the chin, to keep his head clean and warm.

9.

Setting the bread into the oven.

The ovens used both in the bakehouses and in the main kitchens were of the traditional wood-fired kind. To house each oven, tons of insulating sand and rubble were encased within the brick walls of the bakehouses. Inside this mass, the large, flat circular floor of each brick-built oven was surrounded by a low wall, which supported a shallow dome of tiles set edge to edge to form a fireproof chamber. The only entrance was by a doorway at one side – the lintel of which was often pierced by a flue to carry away the smoke and steam from inside, but for the largest ovens in the palace kitchens this was replaced by a huge smoke-hood. To heat the oven, bundles of light branches were used, dry hawthorn being particularly good for this purpose because when ‘bound into faggots … and burnt in ovens and in furnaces … they be soon kindled in the fire, and give a strong light, and sparkleth, and cracketh, and maketh much noise, and soon after they be brought all to nought’.

32

This kind of fuel, in the quantities needed by the palaces, cost £40 a year in the 1540s.

33

Having been set alight, probably by being held over an open fire at the end of a long iron oven-fork, the flaming faggots would be either placed to one side or scattered over the oven floor and allowed to burn out, their flames licking the roof of the oven as they reached towards the open door. Once the brick structure had absorbed sufficient heat, sparks would fly at the mere rubbing of a twig across its dome; a little flour sprinkled on its floor would quickly turn dark brown, but not burst into flame. The bakers may then have taken a long iron bar with an L-shaped end, called a rooker, to rake out most of the ashes, and they would certainly have used a hoe, a semi-circular blade on the end of a long handle, to remove most of the remaining ashes and loose dust. They would then have dipped a long mop called a mawkin into a tub of water and swabbed out the final ashes, thereby introducing a degree of moisture into the oven before inserting the bread.

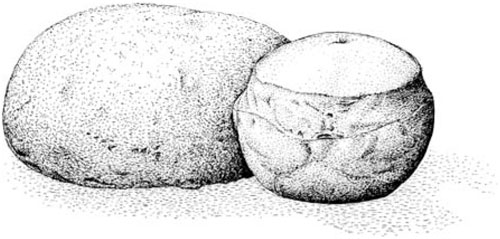

5.

Tudor bread

A cheat loaf of coarse wheatmeal flour, and a manchet of fine unbleached white flour, showing its characteristic dimple on the top and encircling slash.

The fully risen loaves, probably arranged on broad planks or work-boards, were then brought to the oven; each one would be scooped up on to the spade-shaped blade of an oven peel and skilfully set in place within the oven’s dark interior. Now the oven door, probably made of sheet iron, was propped in place and its edges cemented with thick mud or clay, thus totally sealing the new batch until it had finished cooking. Only then was the door removed and the loaves taken out with the peel to cool, finally to be placed in the bread room for storage. Freshly baked bread was con sidered very unhealthy, all those who enjoyed its fine taste and texture fully expecting soon to be suffering from painful heartburn. As Dr Andrew Boorde advised:

Hote breade is unholsom for any man, for it doth lye in the stomacke lyke a sponge, haustyng undecoct humours [causing indigestion]; yet the smell of newe breade is comfortable to the heade and to the harte. [Bread must be] a daye & a nyght olde, nor it is not good when it is past 4 or 5 dayes olde, except the loves [loaves] be great … Olde bread or stale bread doth drye

up the blode or naturall moyster of man, & it doth engender evyll humours, and it is evyll and tarde of dygectyon [slowly digested].

34