All the King's Cooks (7 page)

Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

From the bread store, the clerk of the bakery recorded its distribution to the various offices that would use it. Most went to the Pantry, for the direct use of the household, while smaller quantities went to the Wafery and the Saucery to be used as ingredients in their products. Each day 102 loaves were also sold to the officers of the leash for a farthing each, for feeding the King’s greyhounds.

35

The third part of the outer offices, nearest to the palace, was occupied by the Woodyard.

36

This came under the responsibility of John Gwyllim, the sergeant of the woodyard. In addition to his wages, Gwyllim enjoyed a considerable income from grants made to him by the King. These included the lease of prize wines, and the collection of custom duties as well as the subsidy of taxes and duties from the port and town of Bristol, and the lease of four former Whitefriar’s tenements near St Dunstan’s in Fleet Street, London. He also undertook the unlikely role of purveyor, buying hops and stockfish worth some £335 for Calais and Boulogne in 1545.

37

He and his clerk supervised the delivery of wood and rushes for the court, following the same accounting procedures as those described for the Bakehouse. In the 1540s they were supplying:

38

in Wood for fewell, over and above Bouche of Court | £440 | ||

in Rushes and straw, by estimacion | £60 | ||

in necessaries, as Planks, Boords, quarter | £10 | ||

th’expences of Purveyors and other officers | £6 | 13 | 4d |

£516 | 13 | 4d |

The fuel listed here, used to heat all the public rooms in the palace as well as to maintain all the fires in the kitchens, consisted of

faggots, which were made from the smaller branches so burned fairly quickly, and talshides, timbers of a more substantial size that could maintain the fires throughout the day. Because trees and branches do not come in standard sizes, a quick and efficient method of measuring them had to be developed so that they could be fairly distributed according to the ordinances. Each log appears to have been about four feet (1.2m) in length and classified by its cross-section, as determined by measuring its girth according to a system which was later formalised by Queen Elizabeth.

39

The smallest size – for example a number one talshide, could either be a complete log of about sixteen inches’ (40cm) girth and about five inches’ (13cm) diameter, or of nineteen inches’ (48cm) girth when split down the middle lengthways from a seven-and-a-half-inch (18.5cm) diameter log, or eighteen and a half inches’ (47cm) girth when quarter-split from a ten-inch (25cm) diameter log. There was then a sliding scale extending up to a size seven; the first four sizes would be:

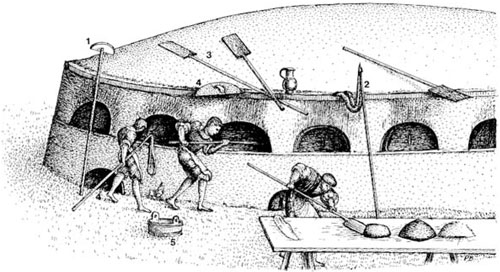

6.

Bread and pastry ovens

This detail based on the painting of

The Field of the Cloth of Gold

(c. 1545) shows Henry VIII’s bakehouse or pastry staff operating a bank of ovens using (1) a hoe to scrape the ashes out of the ovens, (2) mawkins to mop them out, (3) peels for putting the food in the ovens and taking it out, (4) iron oven doors and (5) a tub, probably to hold the clay for sealing the doors.

Size | Complete log | Half-split | Quarter-split |

1 | 16in (40cm) | 19in (48cm) | 18½in (47cm) |

2 | 23in (58cm) | 27in (68.5cm) | 26in (66cm) |

3 | 28in (71cm) | 33in (84cm) | 32in (81cm) |

4 | 33m (84cm) | 39in (99cm) | 38in (96.5cm) |

In this way the volume and burning capacity of each log could be readily measured for purchasing and accounting purposes, and also for meeting the needs of the particular users. In addition, faggots and talshides were supplied to all those who had bouche of court: dukes were allowed eight faggots and ten talshides per day; bishops, senior nobles, the Lords Chamberlain and Privy Seal, the Queen’s maids and the Counting House, six faggots and eight talshides each; knights and senior members of the household staff, four of each; the Wardrobe and household officers, two of each; and the sergeants and gentlemen officers, one of each. Altogether, at least 400 faggots and a similar number of talshides would have been distributed around the palace on each winter’s day.

40

The numerous smoking chimneys must have looked very impressive – the placing of the King’s own apartments and gardens to the south-east of the palace, though, ensured that the prevailing south-west winds would keep them largely smoke-free.

As for the rushes, they would most probably have been the common rush,

Juncus

, whose clumps of tapering tubular green stems grow two feet (61cm) or more in height in most wet heaths and fields in this country. Their main use then was as a floor-covering. Even though many rooms in the palace were fitted with mats made of bulrushes – plaited into four-inch (10cm) strips, then stitched together to make them up to the required size, John Cradocke having obtained a lifetime monopoly in 1539 for supplying them to all the royal palaces within twenty miles of London – loose rushes continued to be strewn.

41

Writing to Wolsey’s physician, Erasmus had described English floors as having accumulations of up to twenty years’ rushes, stinking with the vilest mass of filth and rotting vegetable matter, but neither archaeology nor any contemporary evidence can confirm this.

42

Nicolo di Favri of the Venetian embassy more accurately observed: ‘In England, over the floors they strew weeds called “rushes” which resemble reeds … Every

eight or ten days they put down a fresh layer; the cost of each layer being half a Venetian livre, more or less, according to the size of the house.’

43

To keep the rushes clean, the three grooms who were responsible for strewing them in Edward VI’s Privy Chamber each morning had to sweep away all those that were matted, while the description of Queen Elizabeth’s presence chamber strewn with rushes (which he mistook for straw) given by Paul Hentzner of Brandenburg, travelling tutor to a Silesian noble, and Ben Jonson’s of ‘ladies and gallants languishing upon the Rushes’ show them to have been a clean and relatively high-status floor-covering.

44

Certainly, a monarch as fastidious as Henry VIII would never have allowed masses of stinking rushes to lie about his palace. In practice, the

Juncus

type of rushes provide a warm insulating layer, quiet to walk upon, and give any room a delightfully moist and piquant scent, as anyone knows who has attended the rush-bearing service in St Oswald’s Church at Grasmere in the Lake District.

45

In addition, they help to contain the dust, grit, grease and small litter, leaving the floor quite clean when they are swept up with a broom, and so making them the ideal covering for rooms such as the Great Hall at Hampton Court.

Rushes were also used for other purposes. If their outer layer was peeled off, leaving only a narrow strip to support the fine spongy pith, they could be used as wicks for pricket candles or oil lamps. Henry’s Privy Purse expenses included payments ‘for a potell of salet [salad] oyle 2s 6d; for a bottell and for Rushes to brenne [burn] wt. the saied oyle 3d’; and if dipped in tallow, they formed rush lights and tapers.

46

Dry rushes could be used to light fires or lanterns, or even to make pallets or mattresses for servants.

47

A number of junior officers, such as the under-clerk comptroller, were provided with ‘lytter and rushes for [their] paylette’, while Henry VII’s household regulations include instructions for shaking up a layer of litter – suggesting the manner in which the rushes may have been prepared for the purpose – and laying it between two layers of canvas to form a base for his feather bed.

Running parallel to the river, at the back of the Woodyard, were the stables where the purveyors of the Poultry, the

Bakehouse and the Woodyard could keep their horses. By the 1880s these stables had fallen into ruin and over the course of the following decades, along with every other building in this block, they were demolished and the whole area grassed over, leaving no visual evidence that a major domestic building had ever occupied the site.

The Greencloth Yard

Jewel House, Spicery, Chandlery

Virtually everyone concerned with the domestic management of Hampton Court, along with every item of its food, drink and fuel, had to enter the main palace buildings from the Outer Court by way of the Back Gate (no. 3). As they approached, they would be directly observed by the administrative staff working in the counting house up on the first floor of the gatehouse. At the gateway itself, once the great oak doors had been swung back, they would be challenged by one of the porters. This man was responsible to William Knevet, the sergeant porter who had served as a captain at the siege of Boulogne, and his job was to prevent

any Vagabonds, Rascalls, or Boyes [entering] in at the Gate at any time; and that one of [the porters] shall three or four times in the day make due search through the House, in case that negligently at any time, any Boyes or Rascalls have escaped by them … and put them out again … the said Portes shall have vigilant eyes to the Gate, that they doe not permitt any kind of Victualls, Waxe-lights, Leather Potts, Vessels Silver or Pewter, Wood or Coales, passe out of the Gates, upon paine of losse of three dayes Wages to every of them as often as they offend therein.

1

To enforce their authority, the porters carried their traditional porter’s staff, and also had the use of a pair of small stocks, which were transported from palace to palace in the Greencloths’ carriage.

2

They were probably based in the small room to the right of the Gate, beneath the staircase there (no. 4). From their doorway, not only could they check every person and vehicle entering and leaving the palace, but they could also watch the door of the jewel house only a few feet away, and by scanning the courtyards see anyone entering the boiling house door to gain access to the main kitchens.

The four ground-floor rooms to the left of the gate were occupied by the Jewel House (no. 6). Considering the fabulous value of Henry VIII’s gold, silver and bejewelled artefacts as well as his superb gemstones, this would appear to be a ludicrously insecure and exposed location. But in fact, all those really valuable items were kept in a far safer ‘secret’ jewel house in the King’s apartments, deep in the heart of the palace. This jewel house by the gate was used only to store the less valuable domestic pieces of gold, silver, coinage and so on. Although physically within the household offices, the Jewel House was administered quite independently, the master of the jewels being directly responsible to the King for all items placed in his care; he would issue and receive many whole and broken silver vessels as instructed by the Treasurer of the King’s household, presumably including those intended for the use of the courtiers in the Great Chamber and other rooms of states.

3