Allende’s Chile and the Inter-American Cold War (41 page)

Read Allende’s Chile and the Inter-American Cold War Online

Authors: Tanya Harmer

Even so, as Kelly’s trip to Brasilia demonstrates, international considerations and relationships with foreign actors

did

play a decisive part in the way Chileans themselves made their choices and conceptualized their goals, their options, and their actions. Allende had reportedly been “enraged” when he heard that the Soviets had sold arms to Chile’s traditional rival, not knowing that Peru’s strength had been a key concern for the coup leaders that threatened to depose him. To him, Moscow’s decision—made at the same time as Allende had been exploring the possibility of purchasing its own T-55 tanks from the Soviet Union in early 1973—put Chile in a vulnerable position and was yet one more example of Moscow’s lack of support for La Vía Chilena.

5

While Allende held out for an agreement with the United States, he also thus turned to the Cubans to help him prepare for withstanding a coup, even if he was still unwilling to accept all of their suggestions. Meanwhile, coup plotters looked abroad for reassurance and inspiration while fantastically warning of a forthcoming battle with “15,000 foreign-armed extremists” allied with the Chilean Left.

6

The Cubans were obviously perceived to be the biggest threat in this regard. And, pivotally, it was because of the coup leaders’ fear of the Cubans that they waged a battle against the Cuban Embassy on the day of the coup—without prior U.S. knowledge—and then chased the 120 Cubans stationed in Santiago out of Chile as quickly as they could.

7

Although Chile’s military leaders therefore greatly exaggerated the number of Cubans in Chile and the extent to which the Cubans could undermine

the coup’s success at this stage, their fears reflected the impact that non-Chileans and international concerns had on the escalating struggle within the country. At its heart, the coup was an explicit repudiation of socialism and revolution. And as the country had become a theater of an inter-American struggle over these ideas, an array of hemispheric actors had joined in the struggle for and against revolutionary change. Partly this was because Chileans of different political persuasions had asked them to, but it was also because their own ambitions had drawn them into the conflict. The question of where Chile fit in the world was also of key importance in the battle to define what Chile was going to be: a socialist democracy, a bourgeois democracy, a dictatorship of the proletariat, or a military dictatorship patterned on Brazil.

One of the junta’s priorities, after overthrowing Allende, was consequently to seize control of Chile’s international policy and radically reorient it. Henceforth, the dictatorship abandoned Allende’s embrace of Cuba and the Third World, together with Allende’s aspiration to become a worldwide beacon of peaceful socialist transformation, and instantly drew close to Washington and Brasilia. In its first declaration on the morning of the coup, Chile’s military junta also claimed to be fulfilling a “patriotic” act to “recover

chilenidad

,” proclaiming a month later that “Chile is now Chile again.”

8

Of course, Allende had also come to power promising to recover “Chile for Chileans,” to redefine Chile’s place in the world and radically transform the international political and economic environment. He had also sought U.S. acquiescence and assistance for this project, and, in this respect, the government that took over did the same, albeit with vastly greater success. However, the Chileans whom they purported to be representing and the way they went about doing so were the key differences between the pre- and post-coup regimes. Assuming a different place in the world as a willing member of the United States’ backyard, an implacable foe of international communism, an aspirant of capitalist prosperity, and an internationally condemned dictatorship, the Chile that emerged could hardly have been more different in terms of its foreign relations. As Chilean historian Joaquin Fermandois has noted, the “modern utopia” that some outsiders saw in Allende’s Chile transformed itself into a celebrated “anti-utopia.”

9

Before examining this transformation, we must first turn back to the months preceding the coup. Right up until 11 September, Chile had remained something of a cause célèbre in the Third World even if it had lost much of its initial allure in the Soviet Union, Eastern and Western

Europe, and Latin America. On the eve of a meeting of Non-Aligned Movement leaders in Algiers at the beginning of September, Algeria’s president had pleaded with Allende to attend, if only for twenty-four hours. Chilean diplomats were elected to chair the movement’s Economic Council, and its Council of Ministers sent a strong message of support to Allende on the third anniversary of his election as president of Chile. Yet, on account of domestic tensions, the Chilean president stayed in Santiago, merely responding that this support showed “the growing unity of our countries in a common struggle against imperialism … dependency and underdevelopment.”

10

As events turned out, his letter to Algeria’s president was one of the last in a long line of hopeful statements of this kind. In mid-1973, one Chilean diplomat had also optimistically referred to “an irresistible avalanche” of Latin American and Third World demands that appeared ready to transform international affairs.

11

The stage was indeed set for an avalanche, but it was one that would have ominous implications for the Third World, would destroy Chilean democracy for two decades, and would demolish the chances of socialist revolution in the Southern Cone.

After Chile’s congressional elections in March 1973, preparations for an impending showdown by the Left and Right had become more urgent. As Ambassador Davis wrote in mid-May, “While Chilean politics is still by and large played under the old rules these rules are under new challenge.”

12

Even so, U.S. policy makers were cautious not to pin too many hopes on news of accelerated coup plotting in Chile. The problem was that despite the Nixon administration’s obvious sympathy for military intervention against Allende, it was unimpressed by its progress and therefore hesitant to get involved. Instead, in the months leading up to September, U.S. decision makers debated and disagreed on the issue of bankrolling the Chilean private sector’s strikes to provoke a coup. As before, what concerned those who resisted more involvement was not only the consequences of exposure that could occur for the administration’s domestic and international standing but also the prospect that failure would undermine its three-year campaign to bring Allende’s government down.

In early May 1973 the CIA had reported that plotting was “probably” occurring in “all three branches of the services,” with the air force and navy ready to “follow any Army move.”

13

However, at this stage, analysts accurately acknowledged that the military was divided between constitutionalists

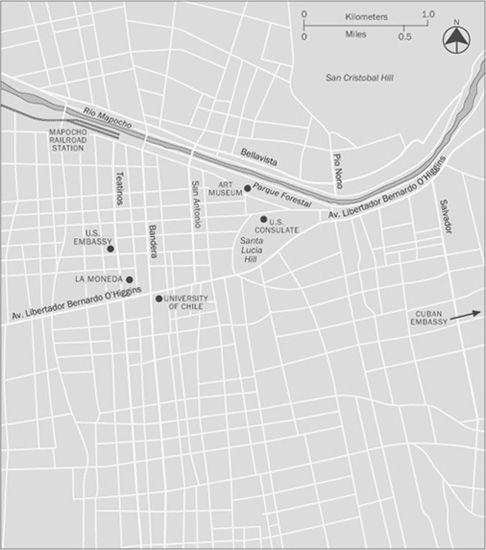

Downtown Santiago

and

golpistas

and that, as a member of the former group, Chile’s commander in chief of the army, General Carlos Prats, would block a coup. Given these circumstances, the director of central intelligence instructed the CIA’s Santiago station on 1 May to “defer” action “designed to stimulate military intervention.”

14

Indeed, despite avid protest from the CIA’s station chief Ray Warren, the director of central intelligence categorically rejected

pleas to reverse his instructions, insisting that Washington needed “more solid evidence” that the military would move and that it had political support before acting.

15

Back in Washington, government agencies—including the Pentagon—did not rate a coup’s chances highly. When CIA and State Department officials discussed covert operations in early June, Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs Jack Kubisch concluded that “a military coup seemed to be a non-starter” owing to the lack of determination among plotters and a general Chilean predilection for “compromise.” A CIA representative at the meeting concurred and those present also agreed that spiraling U.S. domestic criticism of the administration’s covert operations enhanced the risks of greater involvement. Certainly, Harry Shlaudeman, recently appointed as deputy assistant secretary for Latin American affairs after being deputy chief of mission at the U.S. Embassy in Santiago, was recorded as arguing that “the Chileans were fighting Allende on their own initiative, the decisions were theirs. The little edge that we were giving them with our financial assistance was critical,” but as Shlaudeman put it, the United States was “not and must not get into the position of saving them.”

16

The Nixon administration’s fears of failed military intervention in Chile subsequently soared when, on 29 June, an attempted coup against Allende did not succeed in overthrowing the Chilean government. During this Tanquetazo, as it later became known, Chile’s Second Armored Regiment advanced on Santiago’s city center only to be confronted and overpowered by General Prats leading loyal sectors of Chile’s armed forces and Chilean left-wing resistance.

17

To the Left’s delight, and the Right’s dismay, left-wing parties had also succeeded in distributing arms, silencing the opposition’s radio stations, and maintaining communication between themselves and the population throughout the event.

18

However, by proving themselves capable and defiant, Chilean left-wing parties also gave away their evolving tactics for resisting military intervention.

19

Certainly, anti-Allende plotters analyzed their actions closely, and there is evidence to suggest that UP parties and the president’s bodyguard, the GAP, were successfully infiltrated by the military after this failed coup.

20

Meanwhile, U.S. analysts deliberated the future rather slowly. In a memorandum to the CIA’s Western Hemisphere Division chief after the Tanquetazo entitled “What now?” one intelligence officer admitted it was hard to predict what would happen in the immediate future.

21

The Defense

Intelligence Agency (DIA) also reported that in spite of a Chilean governmental crisis, serious plotting had not “gone beyond the planning stage.”

22

By contrast, U.S. intelligence operatives warned that left-wing parties were arming and that, if continued “for any length of time,” the situation would favor the UP.

23

Over a month later, the situation remained unresolved. One CIA informant returning from Santiago explained that “none of our people has a clear solution to the Allende problem…. All feel a sense of frustration.”

24

To be sure, the CIA already had contact with the group of plotters that would launch Chile’s September coup, but U.S. intelligence agencies continued to fear that it would hesitate for too long or that its members would eventually compromise.

25

As Washington tried to find a “solution,” it avoided the UP’s desperate pleas for financial respite and kept up international economic pressures against Allende.

26

In his new position as Chile’s foreign minister, Orlando Letelier implored the United States to resolve financial disputes “rather than wait for … [a] hypothetical successor government.”

27

Even the Chilean Christian Democrat Party’s ex-presidential candidate, Radomiro Tomic, urged Davis to “come forward with some spectacular gesture” to put an end to Chile’s political and economic crisis (he suggested tires or two thousand trucks for strikers).

28

When the World Bank considered issuing a loan to help Allende in July and August, however, the State Department launched a quick diplomatic campaign—providing “extra ammunition” where necessary—to block it.

29

And although Washington failed to convince all Paris Club members to back its obstruction of the loan, Chile’s creditors refused to stand up for Chile, which meant that the World Bank ultimately deferred its decision.

30

Crucially, for Chile’s international position, European creditors were also losing patience with Chile’s inability to meet even rescheduled debt repayments.

31

At a Paris Club meeting in mid-July 1973, only Sweden (an observer to the talks) had defended Chile’s request to defer 95 percent of repayments.

32

Whether economic assistance at this stage would have significantly improved Allende’s chances of saving his presidency is doubtful. As Allende faced crippling strikes and successive cabinet resignations at home, domestic observers and foreign commentators focused more and more on the political and military balance of power within Chile. Wary of backing action that did not have clear public support, the DIA still reported in early August that approximately 40 percent of the army and Chile’s armed police service, the Carabineros, remained loyal to Allende, thus pointing to the prospect of a civil war if the other 60 percent took action.

33

Moreover,

David Atlee Philips, chief of the CIA’s Western Hemisphere Division, noted that the “key piece in the puzzle” was the army, the branch of the armed forces that was least likely to act against Allende and in which the United States had the least influence.

34