America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (16 page)

Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

Luckily for Andrew Jackson, the War of 1812 was that unique exception. Less than a year after his victory in the Battle of Horseshoe Creek, Andrew Jackson led his forces into a more important battle at the Battle of New Orleans. The British hoped to grab as much of the land on the western frontier as they could, especially New Orleans, which had a prominent position on the Mississippi River for trading. With more than 8,000 soldiers aboard a British fleet sailing in from Jamaica in early January 1815, the attack on New Orleans promised to be a significant one, while Jackson’s men defended New Orleans with about half that number. This went on despite the fact that the two sides had signed the Treaty of Ghent on Christmas Eve 1814, which was supposed to end the war. The inability of news to travel fast ensured that the battle would take place nonetheless.

At the beginning of the battle, Jackson and his forces were aided by the weather, with the first fighting taking place in heavy fog. When the fog lifted as morning began, the British found themselves exposed to American artillery. On top of that, Jackson’s men held out under an intense artillery bombardment and two frontal assaults on different wings of the battle, before Jackson led a counterattack. By the end of the battle, the Americans had scored a stunning victory. Jackson’s men killed nearly 300 British, including their Major General Pakenham and his two lead subordinates. More importantly, nearly 1500 additional British were captured or injured, and the Americans suffered fewer than 500 casualties.

The British army had not been fatally wounded, but what the men thought was the first battle in the Louisiana campaign was costly. The British thus decided that the continued campaign – which intended to conquer all of the Louisiana Purchase Jefferson had made just a few years earlier – would be too costly, and would end in defeat. On February 5

th

, 1815, the British retreated by sea, right around the time news was reaching the west that the war had ended.

Though it was an enormous victory for Jackson and the Americans – the most important of the entire war – it proved to be a completely unnecessary one. The Treaty of Ghent had officially ended the war by keeping the status quo ante bellum. This essentially meant that both sides agreed to offer nothing, keeping things as they were before the war. The Battle of New Orleans came in February, when the war was already over, and had the results been different, the British would have been compelled to hand the important port back over.

Regardless, the nation much appreciated Jackson's skills and the Battle of New Orleans was forever christened as one of the greatest in American history. Jackson was honored with a “Thanks from Congress,” which was then the nation's highest military honor. Despite the huge failures of the War of 1812 – the Americans lost almost every battle except New Orleans, and Washington D.C. was destroyed – the nation now had something to celebrate. Andrew Jackson was celebrated as a hero from the West, marking the first time a “Westerner” held a position of national prominence in the United States.

Chapter 4: More Military Glory and a Return to Politics, 1815-1824

Florida and the Seminole War

Though he couldn’t have realized it at the time, Jackson's battles with the Creek Indians were not finished after the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. In 1817, new President James Monroe tapped Jackson to lead an assault on Creek Indians and the Seminoles in Georgia. Meanwhile, after the Treaty of Fort Jackson had paved the way for Americans to move into Alabama and Georgia, many of the Creek Indians had escaped to Florida after the Treaty of Fort Jackson, and Jackson was also ordered to engage them there.

Native Americans weren’t the government’s only concern in the South. One of Jackson’s assignment objectives was to ensure that Florida did not become a holding station for runaway slaves, which was becoming an increasing problem throughout the South, especially with growing political tension with the North. At the same time, Monroe needed Jackson to tread lightly, because the territory was controlled predominantly by Spain, meaning the Creek Indians were launching attacks on Georgia from foreign land.

Jackson's mission was to solve all of these problems, which would require a difficult balancing test. Partly for that reason, President Monroe gave deliberately vague orders, leaving much of the strategy to Jackson. If Jackson decided to engage Spanish or British troops stationed on the peninsula, President Monroe could diplomatically deny that he endorsed the attacked. With that, Jackson had no intention of treading lightly. Having been given so much discretion for his mission, Jackson took the mission into his own hands and decided to act boldly. From the beginning, Jackson made it his mission to annex Florida, going much farther than Monroe anticipated.

From a military standpoint, Jackson’s campaign was an easy one. The Seminoles and Creek Indians were incapable of putting up much of a fight, and Jackson treated them brutally, burning their homes and crops and massacring them.

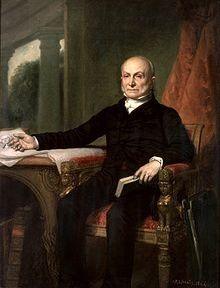

A more subtle problem occurred when Jackson and his men began to fight with Spanish troops and conquered Pensacola, the Spanish-held capitol of Florida. The United States had not declared war on Spain, so Jackson’s move on Pensacola ignited an international dispute. The Spanish were outraged, vehemently asserting that Jackson's invasion was unjust and unwarranted, and even within the Monroe Administration many called for Jackson's removal and censure. One important figure, however, defended Jackson: Secretary of State John Quincy Adams. Quincy Adams believed the Spanish had poorly defended territory that was vulnerable, and Jackson had offered evidence that both the Spanish and the British had supplied the Indians with arms for fighting the Americans.

The Secretary of State thus brought these charges with him to negotiations with the Spanish. Out of this came a favorable result for the United States: the Adams-Onís Treaty, which sold Florida to the United States for $5 million. Jackson was now something of a conquistador, having conquered territory to add to the rapidly expanding country. He was hailed as the country's greatest military leader, and was awarded with the position of Military Governor of the Territory of Florida, a post he held in 1821.

U.S. Senate and Election of 1824

In 1822, the Tennessee Legislature sent Jackson back to the Senate after a 24-year hiatus, which at first glance seems like an odd choice given how much Jackson had detested politics so many years earlier. But things were far different in the 1820s than they had been in the 1790s. This time, when Jackson arrived in the U.S. Senate, he met an Administration that he much preferred to the one he had encountered in 1798. President Monroe was a Democratic-Republican, and was much more favorable to Jackson than Federalist President Adams had been.

Moreover, Jackson’s first stints in politics came when he was a virtual unknown located on the frontier far away from traditional political power bases. This had changed dramatically by the 1820s, as the frontier had pushed even further west and Jackson was the nation’s biggest military hero.

But not everything had changed. When he became Senator, Jackson was once again keeping his eye on another office. Given his credentials, it now made logical sense that he seek the Presidency, and in 1822 he seemed to have a viable chance of winning after Monroe’s second term.

Since the War of 1812, the United States had devolved into a one-party state with the collapse of the Federalists. Thomas Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party was the only national political party, and it dominated the House, Senate and the Presidency for nearly two decades. In 1820, President Monroe ran unopposed for reelection, the only time in American history that an incumbent went unchallenged. Thus, if Jackson could secure the nomination of the Party in 1824, it seemed certain he would be elected President.

The Election of 1824, however, proved to be a watershed in American political history, opening the doors to the present-day two party system. Jackson initially had trouble securing the nomination of the Democratic-Republicans, because the Congressional Caucus nominated William Crawford, the sitting Secretary of the Treasury. Jackson may have been a military hero who was popular with the country, but the nomination process did not involve citizens voting yet, and Jackson now faced an entrenched politician.

Luckily for Jackson, many within the party thought that that method of selection was undemocratic, and that Crawford's nomination was illegitimate. Other candidates thus jumped in the race, believing Crawford stood no chance of winning. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams threw his hat into the race, as did the “Great Compromiser” Henry Clay of Kentucky and, briefly, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, who dropped out after deciding he wanted to be Vice President instead. And finally, Andrew Jackson also decided to run for the White House. Jackson was now running against several Cabinet members and one of the Lions of the Senate.

All of the candidates were members of the Democratic-Republican Party, though John Quincy Adams appealed to the former Federalists in New England thanks to his famous father. On Election Day, Andrew Jackson won a plurality of the electoral votes, but not the needed majority. Quincy Adams solidly won the Northeast, Clay won some of the modern-day Midwest, Crawford won a few Southern States, and Jackson won all of the remaining states. He had earned 99 electoral votes to Quincy Adams' 84, but 131 were needed to win the election.

For the first time since 1800, the election of the President was sent to the House of Representatives. There, Clay endorsed Quincy Adams, giving his electors to him. Quincy Adams thus won the Presidency and immediately appointed Clay Secretary of State, which appeared to be the most basic quid-pro-quo. Andrew Jackson was dismayed, and he and his supporters labeled the deal a “corrupt bargain” indicative of insider politics and not populism. Jackson and his supporters vowed there would be a rematch in 1828.

Quincy Adams

Chapter 5: Jackson’s Presidency, 1828-1837

Election of 1828

In some sense, Jackson's defeat in 1824 only emboldened his case for the Presidency. As Quincy Adams went on to increase the role of the federal government in the economy, Jackson contended that he governed like a Federalist. To Jackson, Quincy Adams' Presidency symbolized the transfer of tax wealth from the common people to the elites. Besides, Jackson could also make the argument that Quincy Adams’s presidency was the result of an unjust bargain of power among D.C. elites anyway. Jackson hoped to represent the common people in the White House, and with that he ran for the Presidency again in 1828.

In 1825, the Tennessee Legislature quickly re-nominated Jackson for President just months after his defeat, setting the stages for a rematch in three years. But in order to smooth the process for Jackson’s candidacy, Jackson and his supporters side-stepped the national Democratic-Republican Party and created their own political organization: the Democrats. The Tennessee Senator and national military hero made an odd choice for his running mate, selecting sitting Vice President John C. Calhoun. No nominating caucus was held for John Quincy Adams, though he did run for reelection as a “National Republican.” In essence, the one party that had ruled the country for nearly 30 years destroyed itself picking a president in 1824, bringing back a national two-party system.

Having resigned from the Senate after the Election of 1824, Jackson spent most of Quincy Adams' Presidency on the campaign trail. With the help of powerful American politicians, including Martin Van Buren, Andrew Jackson essentially remodeled the old Democratic-Republican Party and reassembled much of its coalition under the Democratic Party. Meanwhile, Quincy Adams found himself limited to the constituency that his father attracted, the old Federalists of New England. To fight back, Quincy Adams supporters labeled Jackson a “jackass,” but Jackson liked the term, accepted it, and gave his new political party a mascot that lasts to this day.

On Election Day, the results mirrored those of the days when the Federalist Party was in its last throes. Jackson won handily, carrying all states except those in New England and some in the mid-Atlantic. He won 178 electoral votes to Quincy Adams' 83, ensuring there would be no need for backroom deals to pick a president.

Jackson had just reached the pinnacle of power, but his election was not all fun and excitement. As the “jackass” label suggested, the Election of 1828 included some bitter politicking, and the two sides attacked from every possible angle. During the race, supporters of Quincy Adams seized on the fact Jackson and his wife had gotten married before her divorce from her previous marriage was finalized. Rachel was attacked as a promiscuous woman who believed in bigamy by newspapers supportive of Quincy Adams during the race. When Rachel died of bronchial problems and heart trouble just five days after he was elected, Jackson accused his opponents of causing her undue stress and a premature death.