America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (14 page)

Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

Although Jackson’s education took place in fits and starts, when he was in school he received a fairly comprehensive curriculum. In school Jackson learned some Latin and Greek, though the classical languages seem to have had little effect on him. By the time he reached a school age, Jackson’s temper was already growing more aggressive and hostile, and it frequently manifested itself during his education. Thought he was pious as a young child, Jackson became more and more vicious as he aged, quickly leading his mother to the unfortunate realization that Presbyterian minister was an increasingly unlikely career path for her youngest son. Instead, as the once devout Jackson grew into young adulthood, he infrequently attended church services and began to casually dismiss organized religion altogether. Jackson may have remained a believer throughout his life, but he was done being a very active one.

Jackson also grew tired of education, no doubt due in large measure to his legendarily short attention span. As a teenager, Jackson preferred being wild and frolicsome to contemplative and studious. As fate would have it, Jackson was growing up at the perfect time for the athletic and aggressive teenager who was so fond of adventure. During Jackson’s childhood, political tensions between the American colonies and Great Britain erupted into the American Revolution, and war spread throughout the colonies. This gave the young Jackson – only nine years old when the Declaration of Independence was signed – the chance to find his true passion in the militia.

The Revolutionary War

Jackson would come to be known for his service in the War of 1812, particularly at the Battle of New Orleans, but he was fighting more than 30 years before that. Despite his young age, Jackson managed to serve during the Revolution, fighting as a 13 year old when the British shifted their strategy and began campaigning in earnest in the southern colonies near the end of the war. That may sound foolhardy, but Jackson wasn’t alone in his ambitions. In fact, his mother encouraged the idea; she had put aside her ambitions for a Presbyterian minister son long ago, and Elizabeth bitterly hated the British dating back to her time in Northern Ireland. Mrs. Jackson fervently desired to see the Patriot cause succeed, and having her sons help in the effort would make her proud. Thus, she ensured that her children were ardent Patriots, sealing the deal by telling them stories of British oppression in Northern Ireland with the hopes of inspiring them.

Elizabeth’s wishes would be fulfilled threefold. Andrew and his brothers Hugh and Robert enlisted with a local militia in the final years of the American Revolution, just as the brunt of the fighting moved southward into the Carolinas. Jackson did see some combat, though his age naturally limited his ability to fight. Jackson’s older brother, Hugh, died during a small skirmish known as the Battle of Stono Ferry near Charleston. One evening, the remaining Jackson boys were assigned to guard the home of Captain Land against Tory invasion. In attempting to defend the home, a small troop invaded, and the Jacksons were unable to defend. They escaped through the surrounding marsh and managed to arrive back home in Waxhaw.

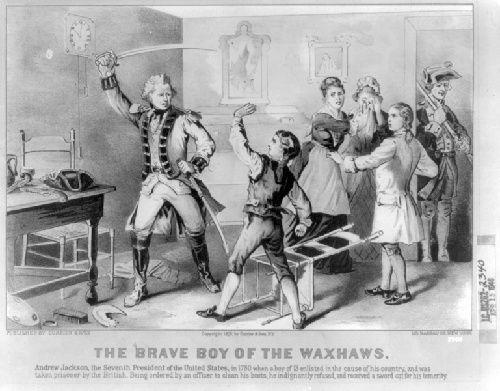

There, however, a British search ensued. Quickly, the British found the Jackson boys and took them as prisoners, destroying the Crawford house in the process. Not surprisingly, the feisty Jacksons did not make for ideal prisoners, and both boys were staunchly disobedient. They did not follow commands from British guards, and Jackson was slashed by a sword for his actions. Jackson, who would later carry a bullet in his body from dueling, was left with scars on his face and left arm for the rest of his life. However, the British imprisonment of American captives became known for poor conditions, and eventually their imprisonment wore the Jacksons down. Robert contracted smallpox and became horribly ill, while Andrew's spirit was eventually broken.

The memorialization of Jackson refusing to clean Major Coffin’s boots

Eventually, with both boys nearly starved to death, Elizabeth attempted to come to the rescue, successfully negotiating for the release of her young sons. Unfortunately, it was too late for Robert, who was so sick by the time of his release that he died within days of being granted a release. While Andrew was still healthy enough to make a recovery, his mother, who had been a volunteer nurse for colonial forces, contracted cholera and died shortly after getting her sons released from prison.

At only 14, Andrew Jackson was now an orphan who had lost both parents and both brothers, his entire immediate family. It was a great tragedy that nobody of any age could fully cope with, and it left Andrew eternally bitter at the British, who he blamed for his personal hardships. As fate would have it, his hatred of the British left him all too eager to take vengeance 30 years later.

Chapter 2: Law and Politics, 1787-1811

Jackson’s Law Career

Once the Revolution over, 14 year old Andrew Jackson was literally starting over with nothing, but he was reaching an age at which he needed to choose a career. He had mixed his formal education with odd jobs, including working for a saddle-maker, but now Jackson chose to establish himself in Salisbury, North Carolina, where he studied under eminent lawyers in the area. Jackson was certainly not the type who could stomach law school, but he came of age in an era where lawyers could still pass the bar by apprenticing.

At the age of 17, Andrew did most of his studying under a lawyer named Spruce McCay. Much of his studying involved copying papers and running errands, but Jackson enjoyed himself nonetheless. Still, the work and errands of a law office were far from able to truly exhaust Jackson's vibrant energy. To compensate, he became a leader of a group of hooligans, wreaking havoc throughout the small town of Salisbury. This was an ironic position for a soon-to-be lawyer, but clearly Jackson, whose childhood innocence was forever lost during the Revolution, was not above acting like a kid.

Nevertheless, Jackson’s work paid off. Jackson was 9 years old when the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776, and on September 26

th

, 1787, just nine days after the United States Constitution was agreed to at the Constitutional Convention, he was admitted to the bar of the state of North Carolina. Less than a year later, Jackson was appointed to be the Solicitor for North Carolina's Western District. Together with a small group of friends, Jackson trekked westward, arriving in an area around modern-day Nashville. There they found political resistance to the government of North Carolina. The western region of the state wanted to secede and form its own state, which would eventually culminate in the state of Tennessee.

In the meantime, however, Jackson remained solicitor for the western region. Because the area was so lightly populated, much of Jackson's work was mundane. Decades before Abraham Lincoln would make the use of the phrase “prairie lawyer” commonplace, it was Andrew Jackson working as a county lawyer on the frontier.

Marriage and Tennessee Constitution

In 1788, Jackson met Rachel Donelson Robards in Nashville, whose family was said to have been some of the first settlers of modern-day Tennessee. Unfortunately for Jackson, Rachel was already married, though her marriage to Lewis Robards was an unhappy one. The two had married in Kentucky, and Rachel had left her husband for Tennessee, but she was still technically married when she met Jackson.

Rachel and her husband agreed to divorce in 1790, and Rachel and Andrew married a year later, in 1791. There was one major problem, however: though Rachel thought her divorce was complete, it wasn't. As it turned out, one of Robards’s friends had planted a fake story in the paper suggesting the divorce was finalized, leading Andrew and Rachel to marry when her marriage to Robards was still valid. Their real marriage was thus delayed for a few years, while Rachel waited for Kentucky to legitimize her divorce to Robards. In 1794, she and Andrew remarried.

Rachel Jackson

Though Andrew and Rachel remained happily married until her death, the controversial nature of their marriage and remarriage was utilized by Jackson’s opponents, even as early as 1806. Insinuations and attacks on his marriage greatly frustrated Jackson and ate at him, and as a man with a short fuse, he felt the need to defend his and his wife’s honor, often resorting to duels. Despite being nearly 40, Jackson became known as a hothead in his community, and he engaged in so many duels that it was only half-jokingly said he “rattled like a bag of marbles” due to all the bullets lodged in his body.

While that quote was made mostly in jest, Jackson did in fact carry a bullet in his body for much of his adult life. In 1806, Jackson dueled Charles Dickinson after Dickinson had attacked him in the local paper. By the 19

th

century, many states were outlawing duels, and historically duels had been viewed as a way to satisfy honor, not take vengeance. Before Alexander Hamilton was killed by Burr in the most famous duel in American history, he had participated in 10 duels without actually shooting an opponent.

This time, though, Dickinson and Jackson were out for blood. In their duel, Jackson allowed Dickinson to fire first, even though Dickinson was known as a crack shot. Dickinson fired first and hit Jackson square in the ribs, with the bullet lodging permanently near his heart. Dickinson was then forced to stand there as Jackson staggered back up to shoot him. Jackson’s shot hit Dickinson right in the chest, killing the man. Though that duel has become part of Jackson’s legend, his contemporaries were not the least bit amused. In fact, Tennessee had outlawed dueling, so the two men had taken their fight to Kentucky. Jackson would also eventually learn that he could not duel with everyone who attacked his marriage.

Shortly after their marriage, Tennessee became a state of its own, the first to be created out of U.S. federal territory. Part of the incentive for statehood was Tennessee's “Indian Problem,” a topic that fascinated Jackson. To help create the new state, he was elected as a delegate to the Tennessee Constitutional Convention.

Jackson's time at the convention was active, though his role was not terribly important. On suffrage, Jackson supported broad rights applied to all residents of the state and supported keeping slavery legal in the state. He also spoke out loudly in favor of fighting and eliminating Native Americans from living in Tennessee.

Early Political Career

Jackson's political career began in earnest with Tennessee's admission to the Union on January 1, 1796. That same year, he was elected as one of the state's first two members of the U.S. House of Representatives. As a Southerner with an agrarian background and a hatred of the British, he was a natural fit for Thomas Jefferson’s nascent political party, which came to be known as the Democratic-Republicans.

Andrew Jackson arrived in Philadelphia in 1796 to serve in the nation's Fourth Congress, which provided a culture shock for the 29 year old. The city was very different from the rugged and unsettled regions Jackson had lived in; unlike the rural Carolinas and Tennessee, Philadelphia was a bustling and elegant place.

When Jackson joined Congress, George Washington had just finished his second term and was retiring, replaced by his Vice President, John Adams. While Washington had attempted to stay above the fray and remain nonpartisan, his Cabinet members, particularly Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, had engaged in sometimes bitter political quarrels, and their opposing ideologies helped bring about the first incarnation of America’s two-party political system: Hamilton’s Federalists vs. Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans.