Among the Bohemians (22 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

Before they were married, Rosalind Thornycroft and Godwin Baynes kept house together with a group of friends in Bethnal Green.

Both were great music lovers and had followed the Ballets Russes since their first arrival in London.

Under their influence, Rosalind took charge of converting the shabby East End house into an oriental bower.

She turned all the beds into divans, and flung over them rich coloured shawls and cushions, which she had picked up as bargains in street markets.

The Caledonian Market was a happy hunting ground for colourful pieces of junk crockery with which she enlivened their drab rooms.

You could live like Schéhérazade for very little.

After the First World War another season of Ballets Russes continued to inspire a new generation of art students, like Robert Medley, who decorated his Belsize Park bedroom in orange, black, lemon-yellow and white in

homage to Benois and Picasso.

Unfortunately the ineradicable green linoleum on the floor rather spoilt the effect.

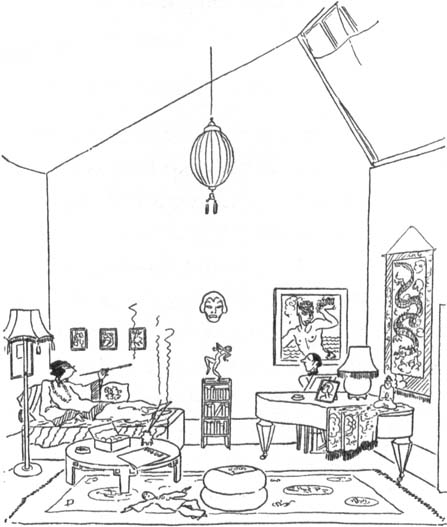

‘First Russian Ballet Period’ from

Homes Sweet Homes

by Osbert Lancaster.

Medley’s friend the writer Mary Butts played out the seraglio scenario for all it was worth.

When Quentin Bell visited this notorious red-headed femme fatale in the rue Montessuy in Paris he was awestruck by the exoticism of her Bohemian pad.

Every surface was strewn with lighted candles, except the floor, which was strewn with underclothes.

Mary, naked except for a bedspread, lounged on the spacious bed, which Quentin inevitably compared to ‘the divan of Sardanapalus as Delacroix painted it’.

It so happened that my father was accompanied on this occasion by a rather proper girlfriend of his called Monica.

The conversation grew stickier by the minute, as Mary first produced a drug peddler wanted by the police from the wardrobe, and then launched into an account of her father’s part in the Crimean War, which involved the use of some highly scatological language.

When Mary discovered bed bugs under the sheets it was the last straw.

Quentin and Monica fled.

Douglas Goldring’s description of Mary’s flat corroborates Quentin’s.

There is the enormous divan again – ‘piled high with purple cushions’ – but he evokes it with the keen interest of someone aware that he is presenting a

museum exhibit of the future.

Every detail tells us not only about the owner of this attic (fourth floor, no lift), but is a component of the time capsule labelled ‘Bohemian sitting-room, circa 1925’:

[There were] three or four rickety chairs, a bright green piece of sculpture by Ossip Zadkine, two flower-pieces by Cedric Morris, a water-colour by Kit Wood and a clever portrait-drawing of Mary by Jean Cocteau.

One wall of the room was taken up by bookshelves which stretched from floor to ceiling and were crammed with all the literature in vogue.

Sex, sociology, Loeb translations, Abramelin, Lévy’s

History of Magic, The Golden Bough

, the

Chansons de Maldoror

, T.

S.

Eliot, Virginia Woolf’s latest, Aldous Huxley, Jean Cocteau, Radiguet’s

Bal de Conte Orgel

– in short, all the ‘period exhibits’ of the future.

On the divan, on top of the purple cushions, lay the sky-blue bulk of

Ulysses

…

Not, perhaps, the ‘readable and entertaining volumes of prose and poetry’ Lady Colin Campbell had in mind to while away the awkward gap before dinner.

Art, arcana, erotica, and clashing colour combinations set the scene for a quintessential Bohemian gathering.

Then Mary gets out the absinthe, and it is the start of a night of intoxication and abandon.

Gwen Otter was another Bohemian of reduced means who had played hostess to the

Jin-de-siède

Chelsea art world but continued in faded glory through the twenties, a little deaf but still capable of a mordant anecdote, a memorial to the passing of aestheticism.

The younger generation were susceptible to her inexhaustible hospitality and happily attended her salon, where they would be sure to meet some lesser celebrity of the art world or, on a good day, some acclaimed star of the Chelsea or Bloomsbury firmament.

Evelyn Waugh was a regular, and recalled the black walls of her drawing room, its gold ceiling, and the piles of’tasselled cushions in the style of the earlier Russian ballet’.

Ethel Mannin went too, and left a detailed description of her hostess’s home:

One passes into a room vaguely like a studio, with a deep blue ceiling, canvas coloured curtains tied up with deep blue glass beads, over the mantelpiece a Venetian mirror, and on the mantelpiece itself a photograph of Epstein’s Tomb of Oscar Wilde, a restaurant-gala-night ‘novelty,’ and a beautiful little alabaster idol with a cheap bead serpent twined ludicrously about its neck… There is a very low divan piled with shabby cushions, in a recess a grand piano thick with dust, an entire wall of the room given over to books, the eighteen-nineties rubbing covers with the very latest of the nineteen-twenties…

Downstairs there is a dining-room designed by Mrs E.

V.

Lucas, canvas-coloured walls with reddish-orange paint-work, striped orange linen curtains, and on the wall opposite the fireplace a John lithograph of Alister [

sic

] Crowley…

The company ate at a table decorated with a single shell in a yellow bowl…

*

Alabaster idols and exotic curiosities had been run-of-the-mill in Bohemia for a century.

The great dandy poet Baudelaire was alleged to have adorned his room with stuffed crocodiles, while the writer and journalist Alphonse Karr hung skulls on the black walls of his attic bedroom.

A taste for the weird and gaudy was nothing new, but this penchant for exotica also displayed a growing admiration for the real qualities of ethnic art that was particularly marked in Bohemia.

The Victorian age was largely blind to the qualities of art outside the Greco-Roman tradition; not so Roger Fry.

In 1910 he made a special visit to Munich to review the Mohammedan exhibition held there, and was one of the first to extol the virtues of the art of the South African bushmen.

Gauguin, Gaudier-Brzeska, Picasso, Braque and Epstein were immeasurably influenced by ethnographic art from Polynesia and Papua New Guinea, with its primitive, elemental forms, and soon aboriginal fetishes began to make their appearance on the tops of Bohemian bookshelves.

The Epsteins were both tireless collectors of exotica.

Jacob amassed such a quantity of rare ethnic sculpture that it was all but impossible to enter the house.

Every room jostled with Easter Island or Benin trophies; shelves and mantelpieces were crowded with priceless objects from ancient Assyria, India, and Africa.

Above his bed towered a pair of six-foot-high figures from Dutch New Guinea.

There was no floor space left, and one could only reach the door to the bathroom by a narrow pathway between the pieces of sculpture.

Henry Moore wondered how he got into bed without knocking something over.

Margaret was just as obsessive, filling her own private ‘treasure chest’ with oddments picked up from visits to auction rooms, costume jewellery, Spanish mantillas, mink coats, embroidered saris.

Number 18 Hyde Park Gate was fast becoming a warehouse for the Epsteins’ collections.

The early decades of the twentieth century were a time when artists found it expedient to travel, for the Continent was much cheaper than England.

In Italy, France and Spain their eyes were opened to inexpensive peasant pottery, brightly woven textiles, woodcarvings, picture frames, cheap colourful glass, kitsch, kitchenware, kites, toys, cushions, and gewgaws of

every kind.

Like pirates returning from a successful foray, artistic tourists came home laden with treasures pillaged from faraway lands, and proceeded to decorate themselves and their environment with memories of their travels.

Take Charleston, admired by historians of decorative art for the boldness of its painted interior, but in some ways equally noteworthy for the profusion of ethnic and Mediterranean odds and ends scattered around the house.

A Chinese Buddha sits in the front hall, a naive Italian fairground figure hangs in the studio; there are Moroccan vases on window ledges, a Benin head in Duncan Grant’s bedroom, a Turkish textile from Broussa over Vanessa’s bed, Spanish plates ranged along the dining-room mantelpiece, Provencal cottons reappearing as lightshades and cushion covers, Venetian chairs.

Charleston is more than a testament to the talented artists who used blank walls and deal tables as carte blanche for their decorative schemes.

It is equally a memorial to travels and holidays, to sunny days fingering the fabric stall in an Arlésien market or a stroll through the souk in Fez.

My environment

reflects the life I’ve led, the places I’ve visited and the people I’ve loved.

Vanessa suffered from a lifelong addiction to pottery shops, for which she was mercilessly teased by her family.

In Ravenna an attractive display of ceramic merchandise tempted her away from her avowed intention to go and appreciate yet more twelfth-century mosaics:

We saw we were undone as soon as we got well inside.

The owner of the shop is a most charming and friendly man whose chief joy and interest in life consists in breeding canaries.

He had them at all ages, in the egg, in the nest, and on the wing, and we had to look at all.

But also he was most sympathetic over pottery and in the end, reckless of consequences, we found ourselves possessed of several large jugs, flasks, bowls, etc.

They are really lovely, a very nice glaze, good colours and shapes, and some very odd and unusual in colour.

But I quite realize our folly and foresee the mockery awaiting our arrival in London…

That wasn’t quite the end of the story however, for the canary man informed Vanessa and Duncan, always in pursuit of the ultimate pot, that all his stock was made in a remote village.

So they set out, and spent a day tracking down the potter.

When they eventually found him he demonstrated his artistry with great aplomb, and the pair had a happy few hours admiring the finished products and buying a great deal more.

Vanessa was able to laugh at herself for her hopeless pot fixation, but her love of strong shapes and unusual colours was deeply rooted, and in her heart she was quite unapologetic.

She could be fiercely condemning of other people’s taste when it fell into what she saw as the fatal traps of prettiness

and refinement.

Staying with her lady artist friends Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson in Oxfordshire she found herself repelled by the contrived and excessive care that had gone into their choice of décor – everything matched, merged and chimed; she found it dispiriting.

It reminded her perhaps of the dull, tasteful gloom of the recent past, the Hyde Park Gate years of her youth with its gloomy colours that wouldn’t show the dirt.

Vanessa’s newly discovered Post-Impressionist aesthetic made her as impatient with elegance and propriety in furnishing as in painting.

*

I’m not afraid of being thought tasteless, because I make my own taste.

For people like Vanessa Bell, Mrs Jennings’s grammatical rules were made to be broken, for if Bohemia stood beyond the portals of mainstream society, then who cared whether the doorstep was white, or green or crimson, or any colour under the sun?

Now your home could be a portrait of your own personality, instead of a reverent reflection of respectability.

Cecil Beaton exactly summarized the Bohemian point of view:

Only the individual taste, in the end, can truly create style or fashion, since it is not concerned with following in the wake of others.

Hence, whatever an individual taste may choose, be it a stepladder or a wicker basket, it must always be based on a deep personal choice, a spiritual need that truly assesses and gives value to that particular ladder or basket.

The beauty of these things is somehow transmitted through the personality of the one who chooses.

It is in our selection, after all, that we betray our deepest selves, and the individualist can make us see the objects of his choice with new eyes, with

his

eyes.

The joy of this position was that it was suddenly no longer necessary to spend large sums of money on Louis Quinze daybeds or festooned cretonne curtains in order to create the right impression.

The vulgar implications of violet notepaper or mixed flower arrangements were irrelevant to these social outsiders.

If you were inwardly beautiful then your room became beautiful as an extension of your personality.

With the new emphasis at the beginning of the twentieth century on the formal qualities of art as opposed to its content, it was now becoming theoretically possible to approach a room as one might a canvas, to enter it and ‘read’ its contents not as expressive of social aspirations, ‘elegant refinement’ and ‘reverent taste’, but with the liberated sensibility of the aesthete.

The true Bohemian simply asked the question, ‘Is this beautiful?’ It was an immensely liberating position.

All beauty needed was a paintbrush, some glue and an experimental spirit.

Harold Acton remembered his college friend Evelyn Waugh settling into domesticity in unfashionable Islington, where he first painted the walls, and then proceeded with William Morris-like zeal to apply his own skills to humble household items: