Among the Bohemians (48 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

*

The dancing went on for the next decade.

Possessed as if by demons, in celebration and forgetfulness, thrashing, vibrating, breathless, the twenties still reverberate to the sound ofjazz bands.

Even before the war, Mrs Grundy had been mustering opposition to the fearsome new ragtime dances with their indecent sexual closeness – the Tango, Turkey Trot and Bunny Hug – that were reaching London’s

thés dansants

from the New World.

Jazz was the latest assailant; its jungle rhythms seemed deeply shocking in an English ballroom.

‘Disgusting… improper… the dance of low niggers in America… the morals of the pig-sty’ – but protests were fruitless.

The dances were unstoppable: the Toddle, the Jog Trot, the Ki-ki-kari, the Missouri Walk, the infamous Shimmy, and worst of all, the Charleston.

Ezra Pound’s floor show exemplified the fatal American influence:

[He] was a supreme dancer [remembered his friend Sisley Huddleston]: whoever has not seen Ezra Pound, ignoring all the rules of tango and fox-trot, kicking up fantastic heels in a highly personal Charleston, closing his eyes as his toes nimbly scattered right and left, has missed one of the spectacles which reconcile us to life.

The barriers were down and the puritans could only wring their hands and write letters to

The Times,

as the beat went on and on.

*

‘Oh, Nina, what a lot of parties.’

(… Masked parties, Savage parties, Victorian parties, Greek parties, Wild West parties, Russian parties, Circus parties, parties where one had to dress as somebody

else, almost naked parties in St John’s Wood, parties in flats and studios and houses and ships and hotels and night clubs, in windmills and swimming-baths, tea-parties at school where one drank brown sherry and smoked Turkish cigarettes, dull dances in London and comic dances in Scotland and disgusting dances in Paris – all that succession and repetition of massed humanity… Those vile bodies…)

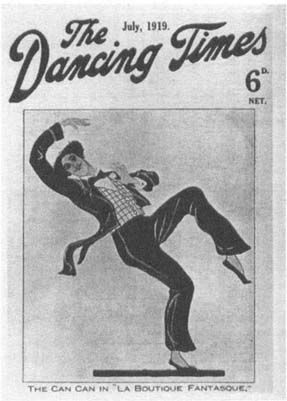

Bohemia’s musical accompanist Ethelbert

White captures the spirit of 1919 for

The

Dancing Times.

Vile Bodies

(1930) by Evelyn Waugh is an insider’s evocation of the 1920s.

Waugh and his contemporaries were deaf to disapproval, bent on pleasure.

They were heady days – of dance and drink, of music and fancy dress, of feasting, flirting and philosophising.

A series of glimpses from some other insiders will give a flavour:

November 1920: John Hope-Jo tinstone invites Carrington and Ralph Partridge to his studio party.

At 10.30 p.m.

Carrington is ready, in silk pyjamas, ‘a frock affaire’ and a shawl.

‘How it brought back another world!

These familiar Bohemian figures.’ The guests are an assorted crew from the café R oyal and a gang of impoverished Fiterovians, with music provided by artists playing guitars and pipes.

They include Lord Berners, ‘Chile’ Guevara, Lilian Shelley, Sylvia Gough, the occasional head-turning Adonis, but most are dingy and drunk – a fevered throng of B-list Bohemians,

singing and reciting poetry, yet somehow depressing, and, Carrington suspected, riddled with disease.

Nevertheless, ‘we danced all the time, and quite enjoyed it’.

The inebriated figure of Augustus John lurched among them all ‘like a cossack in Petruschka, from woman to woman’, while Dorelia sat like a deity in a corner smiling mysteriously, remote, benign and beautiful.

Christmas 1921: the Johns have invited their friends for festivities at Alderney.

The house is full with the home party of Augustus, Dorelia, Edie and eight children.

The guests are Roy Campbell and Mary Garman, Viva King, Trelawney Dayrell Reed, Sophie Fedorovitch, Francis Macnamara and Fanny Fletcher.

Sixteen-year-old Romillyjohn falls in love with Viva at first sight; his state of nervous excitement is almost overwhelming.

On Christmas Eve ‘the revelry went on long and late; we danced and danced’.

At three in the morning a few early birds head for bed.

The stayers toast sprats over the embers of the fire, and finally retire.

On Christmas Day, after much feasting, Trelawney declares that it is time Roy and Mary were married.

With great aplomb he affects an ecclesiastical air and convulses everyone by performing a mock marriage on the drunk and disorderly pair.

There are kisses all round.

March 1923: it is Bunny Garnett’s thirty-first birthday party in Duncan Grant’s studio at 8 Fitzroy Street.

There are twenty-five guests, some old Bloomsbury, some new, some American.

A huge birthday cake is decorated with a design representing Bunny’s fictional creation, ‘Lady into Fox’.

Duncan has talked Bunny into affording Vouvray and still champagne.

The studio fills up.

Carrington is there; she’s bewitched by the beautiful American Henrietta Bingham, who as the evening ends captivates the company by singing Negro spirituals ‘in her soft, faintly husky Southern voice’.

Then Lydia Lopokova arrives from Covent Garden, in time to provide them with a grand finale: ‘She was not too tired to dance for us again.’

Hammersmith, 1928: The poet and painter Norman Cameron has his friends round for an informal evening.

Each new arrival is greeted with a friendly slap round the face with a banana skin, and a glass of gin-and-bitters.

Then there is dancing.

Robert Graves takes the floor, shrieking and rolling about.

Norman makes toast.

‘After this they sat round the stove and meditated, and became quite Russian.’ The intense atmosphere is interrupted by crashes of broken glass, which turns out to be a break-in in the next street.

Even more dramatic entertainment is supplied by a nearby premises catching fire, and everyone rushes outside to see the fun.

This is apparently a typical Hammersmith evening.

April 1929: Brian Howard invites his extensive circle of’haut’ Bohemians

and well-born dilettanti to ‘The Great Urban Dionysia’, at I Marylebone Lane.

The large invitation, 16 inches high, exhorts the recipient to come attired as a definite character in Greek mythology, and recommends that they copy their dresses from the Greek vases in the British Museum.

Viva King goes as Sappho.

A select gathering of kindred souls is guaranteed since, down the borders of the invitation, the host designates all his likes and dislikes.

This was a party with attitude:

J’ACCUSE | J’ADORE |

Ladies and Gentlemen Public Schools Débutantes Sadist devotees of blood-sports ‘Eligible bachelors’ Missionaries People who say they can’t meet so-and-so because ‘they’ve got such a bad reputation, MY DEAR’ Belloc The sort of young men one meets at great, boring, sprawling tea-parties in stuck-up moronic country houses, who say, whenever anyone else says, at last, anything worth saying: ‘Well, I prefer Jorrocks’ and snort into their dung-coloured plus-drawers. | Men and Women Nietzsche Picasso Kokoschka Duncan Grant Jazz Acrobats Russian Films The Mediterranean D. H. Lawrence Stravinsky Diaghilev Havelock Ellis The sort of people who enjoy life just as much, if not more, after they have realised that they have not got immortal souls, who are proud and not distressed to feel that they are of the earth earthy, who do not regard their body as mortal coils, and who are not anticipating, after death, any rubbishy reunion, apotheosis, fulfilment, or ANY THING. |

*

The candle was burning at both ends, its extravagant glow illuminating gatherings of the art world across the city.

Wealth and Bohemia frequently mixed, for this was still an age of patronage.

The cultural aristocracy felt it incumbent on them to provide a milieu where artists could meet each other and cross-fertilise, while reflecting glory on them in the process.

Ottoline Morrell deliberately restricted her invitations to artists, aesthetes and Bohemians, finding that the disapproval of the ‘fashionable’ world inhibited their stimulating gaiety.

She was nevertheless exhaustively conscientious about making introductions, separating bores, and mixing the ingredients of friendship, wit, erudition and beauty.

‘My desire for other people to know each other and be friends is an instinctive, unreasoning passion with me.’ Juliette Huxley never forgot one of her Garsington house parties.

The guests at dinner that night included Clive Bell and Mary Hutchinson, Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, Lytton Strachey, Carrington, Bertie Russell, Brett and Mark Gertler, and the atmosphere was intoxicating:

After dinner coffee was served in the Red Room… and then Philip sat at the pianola and with his usual panache began to play Tchaikovsky and the Hungarian dances… The music floated, powerful and alluring, through the open windows, its rhythm pulsating; one after the other, the guests obeyed the compulsion, threw themselves into Russian ballet stances… outer clothes were stripped off for action, shawls became wings, smoking jackets and ties abandoned to a strange frenzy of leaps and dances by the light of the moon.

The other country outposts of Bohemia often overflowed with guests; at Alderney Manor the children squashed up at the end of the table and the extras slept in gypsy caravans or under the stars.

At Charleston guests were distributed around the attics; the younger generation sometimes sat up all night.

One guest at Charleston remembered, ‘My main memory is of incessant talk.

On one occasion it went on till a winter dawn; why should one ever stop?’

Talk itself was an art form, an ephemeral one, but, for gourmets like Cyril Connolly, delectable in its capacity to add savour to everyday life:

Good talk: the delicious pleasure of explaining modern tendencies to a very great lady: conversation, the only thing worth living for – or so a few of us thought – that bright impermanent flower of the mind…

Now, in the homes of Ottoline Morrell, Ada Leverson, Gwen Otter, the Sitwells, the Epsteins, Violet Hunt, and of course Bloomsbury, meaningless

drawing-room prattle (though not intrigue) was banished, to be replaced by sex, Cezanne, Mallarmé, Ibsen, Vorticism, the Russian ballet, Madame Blavatsky, Truth and Civilization itself as topics of conversation.

Stars of the spoken word like Desmond MacCarthy attracted enthralled listeners.

Bunny Garnett remembered the evenings at which Stephen Tomlin and Oliver Strachey would become locked into some fascinating intellectual argument, or Aldous Huxley held a group of listeners spellbound as he elucidated the history of sexual tastes over the last thousand years.

Many Bohemian parties were memorable for their originality, their inventiveness, the sense of inspiration that pervaded them.

Informality was the common denominator, and Bunny Garnett enjoyed them all – admittedly, the orgiastic parties where lusts were requited among the hats and coats in a downstairs room being for him a particular favourite.

But all tastes were catered for, in a dreamlike succession of entertainments.

There were homosexual parties where the painters Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines entertained their friends by performing the Charleston and Frederick Ashton provided camp cabarets; baroque parties lasting three weeks given by the decadent hanger-on Rudolph Vesey – ‘Heliogabalian and Sardanapalian in the magnitude and lavishness of his hospitality’; Chelsea Arts Balls where the revellers went as Byzantine empresses, Rajput princes, or the back legs of horses; upper-class parties where the Bohemian contingent disgraced themselves by getting drunk; breakfast parties with bacon and eggs and bowls of coffee served in the French way; Hampstead salons full of poetesses in Burne-Jones drapery; midday champagne parties; ‘No More War’ parties; Boat Race parties thronging with beards and fantastic clothes; affected parties full of pouting would-be artists’ models, garish and lipsticked, and clumsy poseurs reading aloud from Swinburne; and mornings-after-the-parties, red-eyed and ravaged, blotched and exhausted.

‘Oh, Nina, what a lot of parties.’

*

And yet it is just possible to characterise this crazy circus.

These parties had in common an identity which amounted to more than just groups of people drinking and dancing, and that identity was both new and of its time.

For a start, a large proportion of them occurred spontaneously.

Kathleen Hale remembered how ‘… one just sprang a party – a certain number of people collected, and some of them could play the guitar and we just started dancing – everything was fluid, and just developed on the spot… Everyone would bring a bottle; it depended what you could afford – sometimes it was just a

bottle of ale; somebody else might take a bottle of sherry, somebody else a bottle of gin – we’d pool the lot, you know.’