An Afghanistan Picture Show: Or, How I Saved the World (16 page)

Read An Afghanistan Picture Show: Or, How I Saved the World Online

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Military, #Afghan War (2001-), #Literary

And yet there is something despicable about it, too.

The do-gooder wanted to do good; he wanted exotic distress to remedy, so he had a sinking feeling on discovering less of that than he had anticipated. To his uneducated eye, it was not always so easy

to tell the difference in condition between refugees and locals:

neither

had what he had! (Whereas those refugee camps in Thailand really had barbed wire; the Young Man saw it on TV.)

The stories—yes, those were sad, but although he thought he believed them, he didn’t; that took a few years of bad dreams. The Afghans could go freely in and out of their camps, and while malnutrition was widespread, starvation seemed nonexistent. The men retained their weapons and frequently slipped back across the border to take part in the jihad. To his eye the camps did not seem to be cesspools of misery at all, but rather festive and “ethnic” like one of those big Fords decorated by Pathan truckers until it was more gorgeous than any Karachi bus, the way its pennant pointed grandly down, bearing in its blackness the many-colored wheel-circle, and its paintings of mosques in blue and gold, captioned by Pushtu cursive like white snakes or breakers, ranged all around the top of the cab, framed by golden waves, and sun and dust had bleached these colors to a milky delicacy so that the truck had become a tea-tin from some dream-Persia, and clusters of bright streamers grew down across the windshield and the son and father leaned against the hood squinting at the Young Man; the tiny daughter, already wearing the long strip of flower-patterned cloth over her hair, gaped at the Young Man in pure frankness, clutching at her throat with one hand, holding a ricepot in the other, and the horizon was nothing but a dusty ridge—so too in the camps with the young girls in their bright-patterned garments, the mud houses graced by sunflowers, the extraordinary strength and handsomeness of the people, the sun and the cloudless sky. —Here for once I do not judge the Young Man so harshly. What if Saint George had come all the way across the Mountains of Doom and found no dragon to slay? Of course he’d be happy that everyone was still alive—

wouldn’t

he?

Dr. Levi Roque, who headed the International Rescue Committee’s field team in Pakistan, pointed out that conditions in Afghanistan were now such that vast increases in the refugee population could well occur. (They have.) —Oh, good, said the Young Man to himself; things will get worse, then. (They have.) He settled into the interview with real enjoyment.

“No amount of medicine can cure them,” Levi said. “We have to educate them. But how? That remains to be seen; it will take a long, long time. That is why we are starting on this wash-your-hands, cut-your-fingernails business. Why is it important that you wash your hands and cut your fingernails? These are the things that they have to learn right now. We are trying our best to do it.”

“How often would you say that refugees ask for medicines that they don’t need?”

“They don’t ask for things they don’t need,” said Levi wryly. “They just ask for

everything

, whether they need it or not. ‘Give me the white pill. Give me this yellow.’ Give me this, give me that. —Oh, I’ll give you an example. We’re doing family planning. We have these contraceptive pills. So. One of these men got hold of our contraceptive pill, because it comes in pink color. And he’s

taking

it, because he loves the color!” —He laughed. —“I hope he don’t get pregnant.”

The Young Man remembered something that Levi had told him earlier. “Do any of them still hold your medical teams at gunpoint?”

“Well, not anymore,” Levi said. “But they always say, ‘All of this medicine belong to us anyway; give us all this!’ But when we give them proper explanation, they say okay. They are stubborn, but they listen … In here, well, the Afghans are lazy. They do not want to help themselves. The Indochinese refugees, they work very hard for themselves. Here,” Levi chuckled, “they don’t help you. You

pay

them, they help you.”

“What do you think the best thing the Americans could do for the refugees would be?”

“I really don’t know,” Levi said. “Well, the Americans are giving a lot of food, and I think they should keep it up.

†

Why? Well, now we are facing so many Afghans already in Pakistan. If we can keep them healthy, that’s a very good sign; that’s very good. We have to anticipate that those Afghans in Afghanistan, in which, in the long run, there might—who knows?—be an emergency, they will cross Afghanistan like the Kampucheans and be dying of hunger. Then we face only one problem—that one, because we keep the refugees here healthy. So that is why, I hope, a lot of people will give more.”

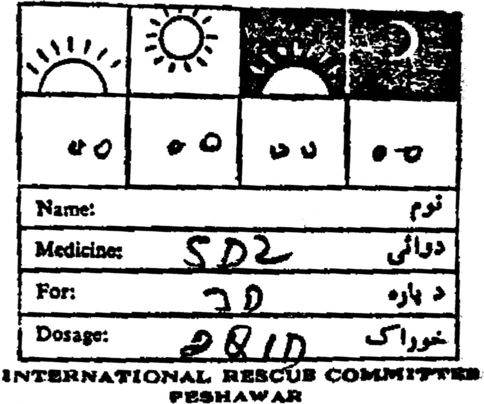

Prescription form for illiterate refugees, the dosage and timing being indicated by the number of pill-symbols blackened and the sun positions

.

Levi was the sort of person that the Young Man had always wanted to be, and never would be. He was quick, brave, effective. During the first outbreak of that disease called Khmer Rouge, he had gone regularly into Cambodia to bring the refugees out. (You knew when you had crossed the border, he said, because suddenly in the jungle you began

to see the bodies.) Sometimes he treated the wounded on the spot. He had flown in and out of Phnom Penh under fire. If

anyone

helped people, Levi did. He gave the Young Man medicines for his dysentery, dark beer and prime cut for his homesickness, and even paperback romances in English for the worst of the hot Peshawar afternoons. (“Dirty books!” said the General.) Everyone got on with Levi, from the pretty girls at the American Embassy to the refugees themselves. And he seemed to run the I.R.C.’s field operation very capably, which meant that he had no illusions about anything.

One morning at around seven they were passing through a bazaar on the way to a checkup of Hangu Camp. It was quite hot already, and they saw a soft-drink stand. —“Pull over there, Hassan,” Levi said. “You two want what to drink? Sprite? Coca-Cola?” —The Young Man and Hassan settled on Sprite. Levi got out to buy the drinks. The Young Man stepped out, too. At once he was required to decline a shoeshine, a hat and a live chicken. Then a kid came up to ask Levi for money. He was a skinny, runty-looking little boy, with his hair cut almost bald in the pragmatic Pakistani fashion. He was a Pathan; he might have been either Pakistani or Afghan. He looked like one of the black-and-white magazine pictures of hungry children whom relief organizations invite you to sponsor. —“I

—no

mother,” he said. “Please, rupees, please.” —Levi laughed, dropping a straw in his drink. —“You don’t have a mother? You’re very lucky. You do what you want; nobody give you a hard time!” And presently they had all finished their sodas, and Hassan started the engine.

Once the Young Man had worked on a ranch in California with a fellow named Mike. Mike was very idealistic. He even believed in Jerry Rubin. Their truck stalled on them one day six miles from the ranch, so they started the walk back to get another vehicle. After they had taken a few steps, Mike saw a beer can. He picked it up. A few steps later he saw another can. He picked it up. The Young Man looked along the

shoulder of the highway where they were walking. As far as he could see there were cans. He pointed this out to Mike. Mike said nothing. Soon his arms were so full of cans that he could not carry any more. They came to the next can. Mike set the cans down and crushed them with his boot; then he gathered them up again. The two of them walked on, Mike always picking up cans, until at last his arms were so full of crushed beer cans that he could not carry any more. The Young Man, who had been anticipating this for some time, waited to see what Mike would do. Mike stopped for a moment, thinking. Then he put his cans down in a neat stack at the side of the road, walked on, and picked up the next can. When they finally reached the ranch, Mike had left little caches of cans behind them for six miles. The ranch manager bawled them out for taking so long to get back. That Saturday, Mike borrowed a truck, collected all his cans with it, and took them to the dump. For a few days, six miles of one side of the highway was pristine.

Thinking about Mike and the beer cans, the Brigadier and the toads, the Afghans and the Russians, the relief groups and the refugees, the Young Man shrugged a little. He supposed that the boy with no mother was one of those cans on the other side of the road. —Then Levi laughed again. —“You know,” he said, “last time I was there, he told me he had no father. I ask him, ‘All right, you have no father; where’s your mother?’ He pointed up the hill and said, ‘Up there.’ Now he’s learning. He’s a very bright boy.”

The refugees kept coming and coming. Year after year, the ants fled the toads. “They have probably killed a hundred thousand Afghans altogether now,” an ex-professor told me in 1984. “Government officials are not killed on the spot; they are given a just trial and sent to jail, but villagers—villagers and freedom fighters—are killed on the spot. This is done regardless of age. If a village is bombed and someone is found alive, even a woman who does not know how to use a machine gun, she is killed on the spot, because her crime is that she helped the

Mujahideen. A child is killed on the spot, a child! Even animals like horses are killed so that freedom fighters cannot use them.”

At some of the camps they sat in the sun for hours in front of the signs:

MALARIA DISPENSARY, TUBERCULOSIS CHECK

. There were not enough doctors.

In the I.R.C. camps near Kohat he very often saw the malnourished infants, tightly swaddled in the heat, too weak to disturb the flies that crawled across their faces.

Then for his Afghanistan Picture Show a young boy whose face was spattered with fine birthmarks like a buttermilk pancake stepped forward smiling with mouth and greenish-black eyes and his friend set a watermelon upon his head!

The old ones sat still. They must know that they would die in Pakistan. The little girls tilted their heads at him and ran away coyly, as little girls seem to do almost everywhere. The men took him inside their mud houses and showed him photographs of the martyred ones—large, grainy black-and-white posters on the walls. They showed him their guns and told him that their sons, their uncles, their brothers were in Afghanistan right now killing Russians, and when the others returned they themselves would go. They smiled.

At Kohat the houses were sometimes grass-roofed castles whose ramparts were molded of mud and gravel. These had baked hard in the sun; they were very hot to the touch. Blankets and bedding lay stretched out on them to dry.

At the little soft-drink stands, fruit stands, cigarette stands, sat vendors indistinguishable from those about Peshawar. It was hot in the camps, though, and often there was no ice for the Fantas and orange sodas. —As for the Young Man, he sat in town, drinking his ten Sprites a day.

In the camps people were polite to him. They never asked him for anything.

Levi’s van pulled up by a dispensary tent. It was only about nine in the morning, so it was not too hot yet; and they were up in the hills anyhow. Then tents and mud houses of the camp were widely spaced, but they went on and on. You could walk up the ridge and across the rolling plateau and up the next ridge and along the hill and up the ridge again and still see no end to it.

The dispensary was crowded. A baby cried. Women in chadors—red or green or black—waited silently. They drew back when the Young Man was brought in. Dr. Tariq had stopped his examinations for the moment in Levi’s and the Young Man’s honor, and his assistant brought them both cups of green

chi

. The baby cried and cried.

“How many people a day do you treat?” said the Young Man, switching on his tape recorder. The Afghans watched in fascination.

“Per day is about three hundred, four hundred patients,” said Dr. Tariq.

“What’s your greatest need here?”

“Well, we would like funds for the X-rays, because most of the people are having tuberculosis. We would like to screen the patient’s immediate family. I mean, like about ten chaps are living in one tent, so when the mother’s got it, I think frankly the children must be having it also. They’re very crowded.

‡

And another immediate requirement, I

should say, is caused by the fact that these people are from a cold climate. They’re not used to the Pakistani climate. It’s very hot here. And especially for the ladies with this thick garment of theirs.” —He pointed to a patient in a chador. —“You see this clothes that she’s wearing? It’s very thick, and they wear it day and night. We’ve been having cases of bleeding from the nose.”

“Too much heat can do that?”