An Appetite for Violets (39 page)

Read An Appetite for Violets Online

Authors: Martine Bailey

Our English guests, those stocky, red-faced travellers, still demanded meat and pudding, beer and tea. Yet even our stout Britons had seen many wonders since first they boarded the Dover packet, so why should they not let their tongues follow?

‘Honeysuckle iced petals,’ scoffed one John Bull, spying my

menu.

‘I should as soon eat a bouquet of flowers. You must serve me solid belly timber, madame, nothing else.’ Yet in one week I had tempted the old duffer with a restoring quintessence of veal. Then at dessert I caught him licking his spoon like a schoolboy as he scooped up a flower of my own exquisite honeysuckle ice.

* * *

After the hotel’s first hey-go-mad season I fell to breeding and all slowed down. I had to loose my satin stays, and Renzo treated me like I was made of crystal. The first task of my empty hours was to write to my mother and Charity, enclosing a handful of gold coins. No reply has ever come back, but I send the money every year and pray it reaches them safely. The writing of that letter started up a right restless hankering to also write to Mrs Garland, for wouldn’t she just burst to know of my being married and the hotel and all? So upstairs in our apartment, with all the racketing of our business carrying on below, I got to writing at last. I rooted about and found my old receipts stuffed into the pages of

The Cook’s Jewel.

And I found Mrs Garland’s best receipt for taffety tart, the very one I’d copied from her box, saucy article that I had been once. It was all in tatters, with butter blots and scabs of ancient pastry ground into the paper.

So it happened that instead of writing a letter, I scribed that receipt in my best hand and started up this journal. Receipt by receipt I conjured those dishes again. And I got to understanding that a Cook Book feeds the fancy like a dish of dreams. As I thought all this stuff, I scribbled my journal, for a letter could never contain all the news I had to tell. So I wrote of all my discoverings and adventures, and how it had all turned out in the end just like the perfect dish.

Then my time of danger came and I was delivered of a strong baby boy, named Giacomo after Renzo’s father. He has Renzo’s dark curls and stubborn cherry mouth, comically mixed with the mulishness of his mother. It is a delight too, to see Evelina dandle her little brother on her knee, for she is the fondest of creatures. Fond and simple, I should say, for though it pains me to write it, her wits are of the dullest. She is a lovely and a happy child, but forever slow and will never master her letters. But I would never change her, for she calls little Jack her own darling brother, and Renzo calls her his own daughter, too.

* * *

Yet each time I thought my journal near finished, some other surprise would arrive. One day as I dandled little Jack in one arm and read the Leghorn newspaper with the other, I started at a familiar name:

At the court of sessions at Leghorn on 2nd July 1776 Mr William Dodsley was indicted for a Felony in taking to Wife Amelia Jane Jesmire on the first of September 1773, his first Wife Dorcas Bertram being then alive and living in London, England. Reverent Emanuel Trouvaine deposed that upon visiting the Mission in Leghorn he did recognise the prisoner drinking punch at the Regatta …

I ran down to the kitchen and cried to Renzo, ‘Goodness, listen to this for a tale.’

And I told him all the import, that this braggart Dodsley had pretended to be a retired sea captain of 400 guineas a year, and claimed to Jesmire that his hired lodgings were his rightful property worth £2,000.

‘Ah, here is word of Jesmire’s situation now,’ I said:

… soon after their marriage he came to Amelia in want of money, which he demanded in Gold, for his Pockets disdained both Silver and Copper. Amelia, who is a lady of more than fifty years, told the court that she had lost a most genteel position to take up with Dodsley, and losing her most excellent connections in Italy had now no other way forward but to seek a domestic position; such of Dodsley’s creditors having already claimed his goods against his debts. His first Marriage being fully proved by papers sent from London, the Jury found him Guilty and he was burnt in the hand with the brand of Bigamy and imprisoned for five years.

‘So that woman who scorned you has had her just reward,’ Renzo said, snatching it from me and smearing it at once with veal stock. ‘The world is just.’

‘I am sorry for her,’ I said. ‘No, truly I am,’ I protested, for he rolled his eyes. ‘For she was one of us that left England five years past. And here am I, married to you and the happiest woman in the world,’ and at that he looked as proud as punch, ‘while she, the silly old trot – has been taught a sorry lesson.’

Yet always there was one of that band from whom I would never have news. How could I not remember him, when the cargoes from Batavia were unloaded at the market, drenching the air with the scent of cloves?

When I first came here I enquired which boats came from the islands, and did any come from Lamahona? None could help me, though one jug-eared old sailor told me the Eastern Indies were made of five thousand islands and no map or chart could ever name them all. Five thousand. It is like searching for a grain of sugar in a pail of salt. Each nutmeg I grate reminds me of Keraf’s island of plenty, heavy with fruits to be lifted and eaten from the branch. As I mix sweet spices I wonder where my friend is now, and whether reunited with Bulan and his son. I fancy he perches on his

prahu

boat out on the ocean, bathed in sunshine, hunting whales and rays and flying fish. I pray so, with all my heart.

* * *

Then I set down my journal and forgot it for one whole year. I was blessed with the safe delivery of a second son whom we named Renzo. He has a mop of hair with a copper glow, and was born with his first tooth cut.

Then an acquaintance arrived in Florence, and I found that my tale was not quite ended. I had pieced together my story from all the broken accounts and receipts, but like a squeeze of lemon in a rich sauce, one last sour note was missing.

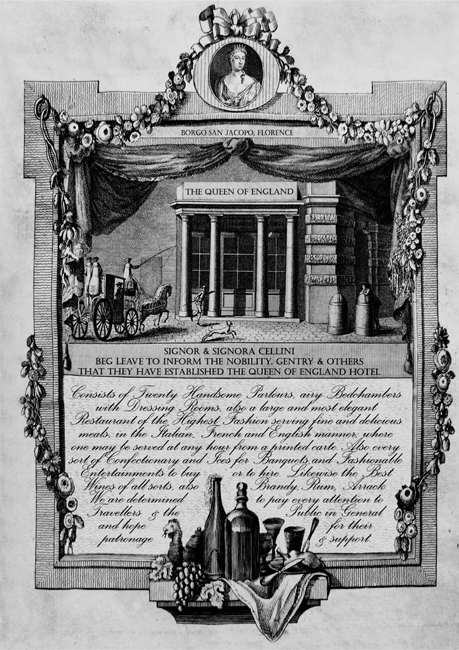

The Queen of England, Florence

Being Advent to Christmastide, 1777

Signora Bibiana Cellini, her journal

It began last year when the Earl of Mulreay and his mistress came back to lodge with us. The old fellow had just arrived in the city from the waters at Spa, his wrinkles powdered to the colour of decay, the outmoded patch stuck to his rouged cheeks.

‘My dearest Mrs Cellini.’ His touch was as dry as old hair papers as he lifted my hand to his puckered lips. At times he reminds me of old Count Carlo, but the earl would no more eat a viper than an oyster out of season. I had heard Count Carlo had snared some other heiress, poor creature.

‘My Lord, have you seen our new

menu?

’

As we discussed each new dish I noticed the pretty

aventuressa

at his side appraising my costume. That was also new from Paris, a Polonaise gown in broad blue stripes, the skirts hitched up in milkmaid fashion.

‘We have a Tiber sturgeon just fresh from the boat. Or a white Tuscan peacock. Or of course, if you care for something more homely, I have a taffety tart of quince and apples just baked.’

His grin showed the toffee-coloured stumps of the dedicated epicure. ‘A taffety tart?’ Clapping the silk-breeched spindle of his leg he smiled like an orphan promised a sugarplum. ‘Bring us what you surmise your best, Mrs Cellini. And the taffety tart with – custard if you have it.’

I was standing half-hid behind a marble pillar watching my serving maid clear the earl’s plates, when I heard him speak a name that knocked the breath from me like a cudgel. Without waiting to consider, I bustled over to the earl’s table.

‘Pray forgive me My Lord,’ I said with my sweetest smile, ‘but the name Tyrone just floated across the air to me. I know the man. Indeed, I owe him a debt of favour. I wonder, perhaps, if it is the same fellow?’

I donned a mask of simplicity as the earl told his tale. The English Braggadocio had arrived in Florence and reckoned himself a first-rate calculator at the gaming tables – but the local nobles had bled him dry. All I heard confirmed that this dupe was Kitt Tyrone.

‘Yet to think of what I owe that gentleman,’ I said, as plaintively as if I trod the boards of Drury Lane. ‘Do you know how I might find him?’

A liver-spotted hand patted my arm. ‘He lodges near the Coco Theatre. God will allow you to perform your good deed, only let the gambling fever abate, Mrs Cellini. He is a sick man. A little ready cash now would only agitate his brain.’

* * *

I retreated to my dressing chamber, but could not sit still. Kitt himself, and here in Florence. Unhappily, I recounted that he had followed his sister to Italy, and even more remorsefully, that his failure to discover her fate was my own doing. Yet why did the fool linger here? Oh Kitt, I beseeched out loud, catching sight of my vexed face in the looking glass. Damn him, I knew he was foolish and weak. God alone knew why, but I had to see him.

I gave myself no time to alter my course, only fretted that such an errand would enrage my husband. He might try to prevent me, might even suspect I was meeting a lover. So I will go in secret, I decided, for silence is best. Next I set on the idea of wearing an ugly black veil such as the local

donne

wear. The very next day while Renzo was out in the city I crept quickly out of a small gate at the back of the Hotel. In a black gown that matched my veil and plain leather slippers, I flattered myself I would pass for any modest Florentine lady.

The alley by the theatre was a dripping tunnel, stinking of ordure. I had to ask the whereabouts of the

Inglese

gentleman, of course. Finally, an old woman pointed a bony finger up a set of stone stairs. I knocked at the door, got no answer, and slowly pushed it open.

Even through the lace mist of my veil I could see the room was of the poorest sort: a stained pallet flung on the cold floor, a window patched with paper. Then I saw empty bottles of raw spirit. And in their midst, as drunk as a tinker, lay the twisted body of Kitt Tyrone.

Pressing my veil to my nose I sank down on a crooked stool beside him and touched his arm. ‘Signore,’ I murmured. ‘Wake up, Signor Tyrone.’

His eyelids rolled and finally opened.

‘Who are you?’ he croaked. I feared I must look like the angel of death in my pall of black lace.

‘A friend,’ I said, in a muffled tone.

He would not look at me, but seemed to be in a delirium, seeking points on the ceiling and walls. Then pulling the stained sheet over his shoulder, he rolled onto his side and blinked at the wall.

‘I am a friend,’ I urged. ‘An English woman who wishes to help you.’

Still he faced the wall, where the marks of vanquished bedbugs made a grim design.

‘Leave me be,’ he groaned.

I sat awhile, confounded. Beneath the sweet fumes of liquor he smelled of sickness, the rotten stink of a truly ailing man. I decided I must take command.

‘Signor Tyrone,’ I said severely. ‘You must come with me to a clean house and be nursed.’

Still he did not lift his eyes from his stupor. Vexed, I decided to surprise him by showing my face. If he knew me, I told myself, he would come to his senses. I threw back my veil, and for a moment was choked by the unwholesome air. Then I stood above him, my countenance open to his gaze.

But it was I who was destined to see how things truly were. His face was as pallid as wax in a tangle of wild hair, yet it was still Kitt’s face that I knew so well. Beneath the startings of a rough beard were his cupid’s lips, and though much sunk, the bones of his face still seemed handsome to me.

Then my vision shifted. It was his eyes that terrified me. I leaned over him, my face as clear as day, that face he had once called pretty. But his eyes still rolled and blinked without a sign of knowing me at all. Poor Kitt, for all my black disguise, was blind.

* * *

It was a terrible task to tell my husband about Kitt. When he returned that night from a banquet he had overseen, it was two hours past midnight. As Renzo undressed I told him of the tragic fall of my mistress’s brother, and his mouth hardened into obstinate silence. Finally, he splashed his weary face with water and sat heavily on the edge of our bed.

‘Are you trying to shame me?’ he asked with a fast hiss of anger. ‘A Florentine wife would never go to a man’s house alone.’

It is true that Italian women do carry a heavy yoke of old-fangled rules. So I made myself very sorry indeed, pleading ignorance, and swearing I was merely trying to do good.

‘It was an act of charity,’ I urged. ‘He is a stranger in the city, attacked by sharpers and somehow grown blind.’

Renzo sighed. ‘It is wood alcohol that has blinded him. He should have known better.’ But when I reached to throw my arms about his neck he jerked away out of reach. ‘As should you,’ he whispered, bitter with hurt. Suddenly I no longer knew where to place my hands. For so long they had found welcome peace around Renzo’s broad shoulders.