An Education

Authors: Nick Hornby

Table of Contents

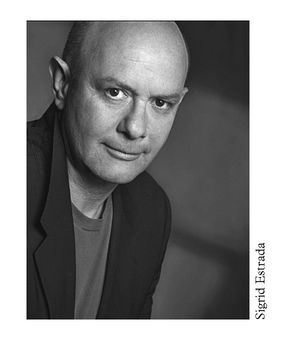

Nick Hornby

is the author of the bestselling novels

Juliet, Naked, Slam, A Long Way Down, How to Be Good,

is the author of the bestselling novels

Juliet, Naked, Slam, A Long Way Down, How to Be Good,

High Fidelity,

and

About a Boy,

and the memoir

Fever Pitch

. He is also the author of

Songbook,

a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award,

Shakespeare Wrote for Money, Housekeeping vs. the Dirt,

and

The Polysyllabic Spree,

and editor of the short story collection

Speaking with the Angel

. A recipient of the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ E. M. Forster Award, and the Orange Word International Writers’ London Award, 2003, Hornby lives in North London.

and

About a Boy,

and the memoir

Fever Pitch

. He is also the author of

Songbook,

a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award,

Shakespeare Wrote for Money, Housekeeping vs. the Dirt,

and

The Polysyllabic Spree,

and editor of the short story collection

Speaking with the Angel

. A recipient of the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ E. M. Forster Award, and the Orange Word International Writers’ London Award, 2003, Hornby lives in North London.

Also by Nick Hornby

FICTION

HIGH FIDELITY ABOUT A BOY HOW TO BE GOOD

A LONG WAY DOWN SLAM

JULIET, NAKED

NONFICTION

FEVER PITCH

SONGBOOK

THE POLYSYLLABIC SPREE HOUSEKEEPING VS. THE DIRT SHAKESPEARE WROTE FOR MONEY

ANTHOLOGY

SPEAKING WITH THE ANGEL

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.)

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi—110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

AN EDUCATION: THE SCREENPLAY

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

RIVERHEAD is a registered trademark of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

The RIVERHEAD logo is a trademark of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First Riverhead trade paperback edition: October 2009

eISBN : 978-1-101-14868-6

INTRODUCTION

The First DraftI knew the moment I’d finished Lynn Barber’s wonderful autobiographical essay in

Granta

, about her affair with a shady older man at the beginning of the 1960s, that it had all the ingredients for a film. There were memorable characters, a vivid sense of time and place - an England right on the cusp of profound change - an unusual mix of high comedy and deep sadness, and interesting, fresh things to say about class, ambition and the relationship between children and parents. My wife, Amanda, is an independent film producer, so I made her read it, too, and she and her colleague Finola Dwyer went off to option it. It was only when they began to talk about possible writers for the project that I began to want to do it myself - a desire which took me by surprise, and which wasn’t entirely welcome. Like just about every novelist I know, I have a complicated, usually unsatisfactory relationship with film writing: ever since my first book,

Fever Pitch

, was published, I have had some kind of script on the go. I adapted

Fever Pitch

for the screen myself, and the film was eventually made. But since then there have been at least three other projects - a couple of originals, and an adaptation of somebody else’s work - which ended in failure, or at least in no end product, which is the same thing.

Granta

, about her affair with a shady older man at the beginning of the 1960s, that it had all the ingredients for a film. There were memorable characters, a vivid sense of time and place - an England right on the cusp of profound change - an unusual mix of high comedy and deep sadness, and interesting, fresh things to say about class, ambition and the relationship between children and parents. My wife, Amanda, is an independent film producer, so I made her read it, too, and she and her colleague Finola Dwyer went off to option it. It was only when they began to talk about possible writers for the project that I began to want to do it myself - a desire which took me by surprise, and which wasn’t entirely welcome. Like just about every novelist I know, I have a complicated, usually unsatisfactory relationship with film writing: ever since my first book,

Fever Pitch

, was published, I have had some kind of script on the go. I adapted

Fever Pitch

for the screen myself, and the film was eventually made. But since then there have been at least three other projects - a couple of originals, and an adaptation of somebody else’s work - which ended in failure, or at least in no end product, which is the same thing.

The chief problem with scriptwriting is that, most of the time, it seems utterly pointless, especially when compared with the relatively straightforward business of book publishing: the odds against a film, any film, ever being made are simply too great. Once you have established yourself as a novelist, then people seem quite amenable to the idea of publishing your books: your editor will make suggestions as to how they can be improved, of course, but the general idea is that, sooner or later, they will be in a bookshop, available for purchase. Film, however, doesn’t work that way, not least because even the lower-budget films often cost millions of pounds to make, and as a consequence there is no screenwriter alive, however established in the profession, who writes in the secure knowledge that his work will be filmed. Plenty of people make a decent living from writing screenplays, but that’s not quite the same thing: as a rule of thumb, I’d estimate that there is a 10 per cent chance of any movie actually being put into production, especially if one is working outside the studio system, as every writer in Britain does and must. I know, through my relationship with Amanda and Finola and other friends who work in the business, that London is awash with optioned books, unmade scripts, treatments awaiting development money that will never arrive.

So why bother? Why spend three, four, five years rewriting and rewriting a script that is unlikely ever to become a film? For me, the first reason to walk back into this world of pain, rejection and disappointment was the desire to collaborate: I spend much of my working day on my own, and I’m not naturally unsociable. Signing up for

An Education

initially gave me the chance to sit in a room with Amanda and Finola and Lynn and talk about the project as if it might actually happen one day, and later on I had similar conversations with directors and actors and the people from BBC Films. A novelist’s life is devoid of meetings, and yet people with proper jobs get to go to them all the time. I suspect that part of the appeal of film for me is not only the opportunity for collaboration it provides, but the illusion it gives of real work, with colleagues and appointments and coffee cups with saucers and biscuits that I haven’t bought myself. And there’s one more big attraction: if it does come off, then it’s proper fun, lively and glamorous and exciting in a way that poor old books can never be, however hard they try. Even before this film’s release, we have taken it to the Sundance Festival in Utah, and Berlin. And I have befriended several of the cast, who, by definition, are better-looking than the rest of us . . . What has literature got, by comparison?

An Education

initially gave me the chance to sit in a room with Amanda and Finola and Lynn and talk about the project as if it might actually happen one day, and later on I had similar conversations with directors and actors and the people from BBC Films. A novelist’s life is devoid of meetings, and yet people with proper jobs get to go to them all the time. I suspect that part of the appeal of film for me is not only the opportunity for collaboration it provides, but the illusion it gives of real work, with colleagues and appointments and coffee cups with saucers and biscuits that I haven’t bought myself. And there’s one more big attraction: if it does come off, then it’s proper fun, lively and glamorous and exciting in a way that poor old books can never be, however hard they try. Even before this film’s release, we have taken it to the Sundance Festival in Utah, and Berlin. And I have befriended several of the cast, who, by definition, are better-looking than the rest of us . . . What has literature got, by comparison?

I wrote the first draft of

An Education

on spec, sometime in 2004, and while doing so, I began to see some of the problems that would have to be solved if the original essay were ever to make it to the screen. There were no problems with the essay itself, of course, which did everything a piece of memoir should do; but by its very nature, memoir presents a challenge, consisting as it does of an adult mustering all the wisdom he or she can manage to look back at an earlier time in life. Almost all of us become wiser as we get older, so we can see pattern and meaning in an episode of autobiography - pattern and meaning that we would not have been able to see at the time. Memoirists know it all, but the people they are writing about know next to nothing.

An Education

on spec, sometime in 2004, and while doing so, I began to see some of the problems that would have to be solved if the original essay were ever to make it to the screen. There were no problems with the essay itself, of course, which did everything a piece of memoir should do; but by its very nature, memoir presents a challenge, consisting as it does of an adult mustering all the wisdom he or she can manage to look back at an earlier time in life. Almost all of us become wiser as we get older, so we can see pattern and meaning in an episode of autobiography - pattern and meaning that we would not have been able to see at the time. Memoirists know it all, but the people they are writing about know next to nothing.

We become other things, too, as well as wise: more articulate, more cynical, less naïve, more or less forgiving, depending on how things have turned out for us. The Lynn Barber who wrote the memoir - a celebrated journalist, known for her perspicacious, funny, occasionally devastating profiles of celebrities - shouldn’t be audible in the voice of the central character in our film, not least because, as Lynn says in her essay, it was the very experiences that she was describing that formed the woman we know. In other words, there was no ‘Lynn Barber’ until she had received the eponymous education. Oh, this sounds obvious to the point of banality: a sixteen-year-old girl should sound different from her sixty-year-old self. What is less obvious, perhaps, is the way the sixty-year-old self seeps into every brush-stroke of the self-portrait in a memoir. Sometimes even the dialogue that Lynn provided for her younger version - perfectly plausible on the page - sounded too hard-bitten, when I thought about a living, breathing young actress saying the words. I had been here before, in a way, with the adaptation of

Fever Pitch

. In a memoir, one tries to be as smart as one can about one’s younger self - that’s sort of what the genre is, and that’s what Lynn had done. In a screenplay, however, one has to deny the subject that insight, otherwise there’s no drama, just a character understanding herself and avoiding mistakes.

Fever Pitch

. In a memoir, one tries to be as smart as one can about one’s younger self - that’s sort of what the genre is, and that’s what Lynn had done. In a screenplay, however, one has to deny the subject that insight, otherwise there’s no drama, just a character understanding herself and avoiding mistakes.

The other major problem was the ending. Lynn Barber nearly threw her life away, nearly missed out on the chance to go to university, nearly didn’t sit her exams. And though lots of movie endings derive their power from close shaves, they tend to be a little more enthralling: the bullet just misses the hero, the meteor just misses our planet. It was going to be hard to make people care about whether a young girl got a place at Oxford, no matter how clever she was. Lynn became Jenny after the first draft or two; there were practical reasons for the change, but it helped me to think about the character that I was in the process of creating, rather than the character who existed already, the person who had written the piece of memoir: I could attempt to raise the stakes for Jenny, whereas I would have felt more obliged to stick to the facts if she had remained Lynn.

Some stories mean something, some don’t. It was clear to me that this one did, but I wasn’t sure what, and the things it meant to me weren’t and couldn’t be the same as the things it meant to Lynn: she had found, in this chapter of her life, all sorts of interesting clues to her future, for example, but I couldn’t worry about my character’s future. I had to worry about her present, and how that present might feel compelling to an audience. It would take me several more drafts before I got even halfway there.

BBC FilmsThe first time I had a formal conversation with outsiders in the film industry about

An Education

, it didn’t go well. Somebody who was in a position to fund the film - because Amanda and Finola, as independent producers, do not and cannot do that - had expressed an interest, read my first draft, invited us in to a meeting. His colleague, however, clearly wasn’t convinced that there was any potential in the film at all, and that was that.This reflected a pattern repeated many times over the next few years: there was interest in the script, followed by doubts about whether any investment could ever be recouped. Sometimes it felt as though I was in the middle of writing a little literary novel, and going around town asking for a £4 million advance for it. Our belief in the project, our conviction that it could one day become a beautiful thing, was sweet, and the producers’ passion got us through a few doors, but it didn’t mean that we weren’t going to cost people money. Another problem with the film’s commercial appeal was beginning to become apparent, too: the lead actress would have to be an unknown - no part for Kate or Cate or Angelina here - and no conventional male lead would want to play the part of the predatory, amoral, possibly lonely David, the older man who seduces the young girl. (Peter Sarsgaard, who responded and committed to the script at an early stage, is a proper actor: he didn’t seem to worry much about whether his character would damage his chances of getting the lead in a romantic comedy.)

An Education

, it didn’t go well. Somebody who was in a position to fund the film - because Amanda and Finola, as independent producers, do not and cannot do that - had expressed an interest, read my first draft, invited us in to a meeting. His colleague, however, clearly wasn’t convinced that there was any potential in the film at all, and that was that.This reflected a pattern repeated many times over the next few years: there was interest in the script, followed by doubts about whether any investment could ever be recouped. Sometimes it felt as though I was in the middle of writing a little literary novel, and going around town asking for a £4 million advance for it. Our belief in the project, our conviction that it could one day become a beautiful thing, was sweet, and the producers’ passion got us through a few doors, but it didn’t mean that we weren’t going to cost people money. Another problem with the film’s commercial appeal was beginning to become apparent, too: the lead actress would have to be an unknown - no part for Kate or Cate or Angelina here - and no conventional male lead would want to play the part of the predatory, amoral, possibly lonely David, the older man who seduces the young girl. (Peter Sarsgaard, who responded and committed to the script at an early stage, is a proper actor: he didn’t seem to worry much about whether his character would damage his chances of getting the lead in a romantic comedy.)

Other books

Sunset Mantle by Reiss, Alter S.

The Earl’s Mistletoe Bride by Joanna Maitland

The Unknown Shore by Patrick O'Brian

Worlds Apart by Barbara Elsborg

The Elfbitten Trilogy by Leila Bryce Sin

Delusion Road by Don Aker

Cowgirl Up by Cheyenne Meadows

Blue Skies by Catherine Anderson

Secrets of the Deep by E.G. Foley

Mortal Friends by Jane Stanton Hitchcock