Ancient Aliens on the Moon (5 page)

Read Ancient Aliens on the Moon Online

Authors: Mike Bara

As part of our research for

Dark Mission

, Richard C. Hoagland also discovered that The Brookings Report was the basis for Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick’s seminal film

2001: A Space Odyssey.

In fact, according to a 1968

Playboy

interview, Kubrick could quote from the Brookings Report chapter and verse. In the interview, he quoted the exact passages shown above, and declared that the whole question of covering up the discovery of artifacts to be the central theme of his legendary film.

From early on, Brookings officially affirmed NASA’s expectation that the agency would inevitably fly to nearby planets in the solar system, and would thus be physically capable, for the first time, of confronting “extraterrestrials” right in their own backyard. Obviously, this goes a long way to explaining the sometimes irrational “skepticism” that most mainstream NASA- funded scientists have regarding the whole ET question. It also might go a long way to explaining some of NASA’s later behavior as their exploration of the solar system actually began.

Armed with this new legal and political cover, both NASA and the Soviet space programs were free to begin going to the Moon and beyond. The Russian were the first to try.

The Soviet Luna program began in 1957 and its objective from the beginning was to successfully send an unmanned probe to the Moon and crash it there. While this may seem like a goal of questionable value today, at the time it would have been a major achievement on the scale of Sputnik itself. But when the idea was first conceived, no one knew for certain just how difficult it would turn out to be to actually navigate to the Moon, much less to the Moon and back as would be necessary for a manned mission to our nearest neighbor.

As I extensively documented in

The Choice

, and as Richard C. Hoagland and I covered in the extended edition of

Dark Mission

, it turned out that simply launching a probe into Earth orbit and then aiming it at and actually hitting the Moon was quite a challenge. Flatly, it should not have been. The mathematics involved and the calculations for gravity were well known, even in the late 1950’s. All that should have been required was to get a probe up into space and then fire the rocket to the point the Moon would be in a few days. The Moon, after all, has a diameter of more than 2,160 miles. That’s a pretty big target. But neither the Russians nor the Americans could seem to figure out this seemingly straightforward task.

The Russians were the first to try. Their first three attempts, named Luna-1958A, 1958B and 1958C all failed in the ascent stage of the mission due to problems with the boosters. It wasn’t until Luna 1, actually the 4

th

Luna mission, that the Soviets finally got a Luna probe into orbit (the Russians had a habit of not officially recognizing their unsuccessful missions). Once there, the Russians took aim, fired their 3

rd

stage rocket, and propelled Luna 1 at its intended target – the Moon, some 239,000 miles away.

And they missed. By far more than the proverbial mile. By 3,725 of them to be exact.

Again, not to overemphasize points I have already made in

The Choice

and

Dark Mission

, but that is simply not possible if Newtonian mechanics is correct. To miss the Moon by more than one and a half times its own diameter when you’re already weightless and in Earth orbit is pretty much impossible, unless the laws of physics are somehow far different than we have been led to believe.

Meanwhile, the U.S. didn’t fare much better. In early 1959 a JPL constructed satellite, Pioneer 4, missed the Moon by a whopping 37,000 miles, more than

17 times

the Moon’s diameter! Obviously, there were issues with navigating the space between Earth and our nearest neighbor, issues which were not successfully solved until many years later, when the Ranger 4 spacecraft lost all power shortly after achieving orbit, and subsequently did what no other American probe had yet been able to do – actually

hit

the Moon. Eventually, von Braun and NASA figured out that having active, spinning systems on board the spacecraft added energy to the system, and once they empirically accounted for this the era of modern lunar exploration really began (see

The Choice).

The U.S. programs started with the Ranger series in the early 1960’s. These were designed to fly into the Moon at high velocity, transmitting back television images the entire way to give humans the first close-up views of the lunar surface. As I discussed in

The Choice

, there really wasn’t a fully successful Ranger mission until Ranger 7 in 1964, but the program allowed von Braun and NASA to figure out the hidden physics of interplanetary navigation. Ranger was soon followed by two new and parallel programs, Lunar Orbiter, which was to take reconnaissance photographs and map the entire surface of the Moon, and Surveyor, which was to test the ability to soft land on the lunar surface and study it.

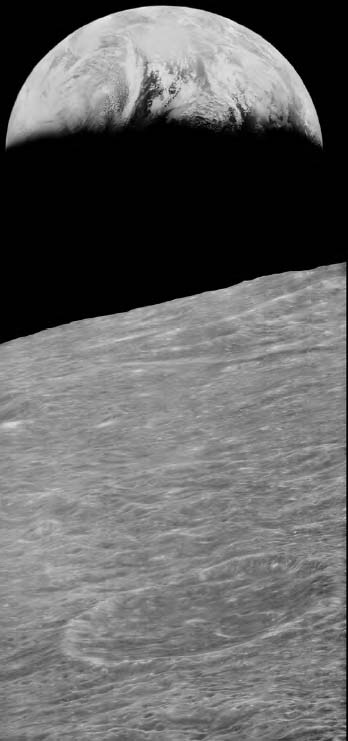

The Lunar Orbiter series was highly successful, with all five missions being completed essentially as planned. Lunar Orbiter 1 was obviously the first in the series, launched in August 1966, and it was to photograph the equatorial section of the Moon’s near side so NASA could scout for possible manned landing sites. From an altitude that varied from 36 to 25 miles above the lunar surface, Lunar Orbiter 1 took some 42 high resolution and 187 medium resolution “frames” of the lunar surface (the camera was a line-by-line scanning system that transmitted images back to Earth as “framelets” that were lined up and reassembled as full images on Earth). The most famous image from Lunar Orbiter 1 was of the first view ever of the Earth from lunar orbit.

Once its mission was complete and its film exhausted, the spacecraft was deliberately crashed into the lunar surface in order to test NASA’s ability to remotely track the vehicle.

Like Lunar Orbiter l, Lunar Orbiter II (November, 1966) was designed as a landing site reconnaissance mission of the Moon’s equatorial region from high altitude (32 miles). It took a total of 609 high resolution and 208 medium resolution frames but because of the altitude, they were of questionable value. Lunar Orbiter II did become famous for an oblique view of the peak of the crater Copernicus which was hailed at the time as one of the great photos of the 20

th

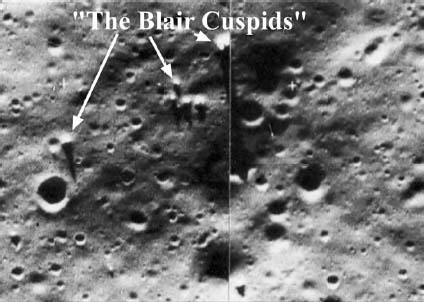

century. But the most interesting photo Lunar Orbiter II took was by far image number LO2-61H3, which showed peaks that came to be known simply as “The Blair Cuspids.”

On November 22, 1966, – three years to the day from the date President Kennedy had been killed — NASA released a Lunar Orbiter II image from the Moon in the vicinity of the crater Cayley B in the Sea of Tranquility. In it, there were objects casting extremely long shadows that seemed to imply that the objects themselves were “towers” of seventy feet or more. Such objects, if they really were present on the lunar surface, would almost by definition be artificial. Eons of meteoric bombardment would have long since blasted any such naturally occurring objects into dust.

The “spires” were first reported on by Thomas O’Toole in the Washington Post the day after they were photographed. A subsequent article in Newsweek magazine added to the intrigue, and William Blair, a Boeing Company anthropologist, was the first to closely scrutinize them. Blair had extensive experience examining aerial survey maps to look for possible prehistoric archeological sites in the Southwest United States. In articles for the

Los Angeles Times

and then the

Boeing News

, Blair noted that the “spires” had a series of contextual, geometric relationships to each other. “If such a complex of structures were photographed on Earth, the archeologist’s first order of business would be to inspect and excavate test trenches and thus validate whether the prospective site has archeological significance,” he was quoted in the L.A. Times.

LO frame 67-H-218

Lunar Orbiter image LO2-61H3 (NASA)

The response from Dr. Richard V. Shorthill of the Boeing Scientific Research Laboratory was swift. “There are many of these rocks on the Moon’s surface. Pick some at random and you eventually will find a group that seems to conform to some kind of pattern.” He went on to claim that the long shadows were caused by the fact that ground was sloping away from relatively short objects, thereby elongating the shadows.

Blair’s rebuttal would later put Shorthill’s arguments in their appropriate context: “If this same axiom were applied to the origin of such surface features on Earth, more than half of the present known Aztec and Mayan architecture would still be under tree- and bush-studded depressions—the result of natural geophysical processes. The science of archeology would have never been developed, and most of the present knowledge of man’s physical evolution would still be a mystery.”

Subsequent analysis seemed to indicate Shorthill was wrong on all counts.

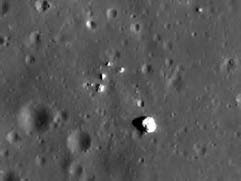

In 2001, Lan Fleming of a group calling itself the Lunascan Project, conducted an analysis of the “Blair Cuspids” as they were now known and concluded that the long shadows were caused by tall, spire-like objects. Later analysis indicated that the objects might not be so exceptional after all, and despite Blair’s “limited and highly speculative analysis of suspect coordinate relationships” that seemed to indicate the objects were distributed according to tetrahedral geometry, the general consensus today is that the “Blair Cuspids” are fairly normal boulders that were photographed under unusual lighting conditions. Current Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter images would seem to support that conclusion.

Lunar Orbiter III was the most prolific of the landing site missions, taking nearly 700 medium and high resolution images of the lunar surface from about 30 miles up. The final two missions,

Lunar Orbiters

IV and V, were high altitude missions designed for overall lunar mapping purposes. All of the Orbiters were subsequently crashed into the lunar surface intentionally to study tracking capabilities and measure the impacts themselves.

Having paved the way for landing site selection, the Lunar Orbiters could be set aside for the far more important Surveyor series. Surveyor, it turned out, was critically important because until one actually landed on the Moon’s surface, no one was quite sure what they would find there. In the 1950’s, Thomas Gold, an Austrian-born astrophysicist and professor of astronomy at Cornell University, speculated that the lunar regolith (the powdery dust that covers the entire lunar surface) might be as much as 10 feet deep in some places, making a safe landing on the surface well-nigh impossible. Gold later revised his assessments, and his revised prediction of the depth of the Moon dust (1-2 inches) turned out to be uncannily accurate. But his studies certainly concerned NASA enough that the Surveyor program was considered a high priority.

The “Blair Cuspids” today? (NASA/LRO)

The Surveyor missions also served other purposes that were equally critical. While the Soviet’s had achieved the first soft landing on the Moon in 1966 with Luna 9, the U.S. had not done so and Surveyor was designed to test the landing radar systems and retro-rocket technology that would be used to land men on the Moon itself. Equipped with a high resolution television camera, Surveyor would be the first U.S. spacecraft to broadcast live images (as still photographs) from the Moon’s surface.