Ancient Iraq (35 page)

CHAPTER 19

The great revolt of 827

B.C

. was not a dynastic crisis in the usual sense of the term; it was an uprising of the rural nobility and of the free citizens of Assyria against the great barons of the kingdom: the rich and insolent provincial governors to whom Ashurnasirpal and his successor had entrusted the lands they had conquered, and the high officials of the court, such as the

turtanu

Daiân-Ashur, who, in the last years of Shalmaneser, had assumed powers out of proportion to the real nature of their duties. What the insurgents wanted was a king who really governed and a more even distribution of authority among his subordinates. They were fighting for a good cause, with the crown prince himself at their head, but a thorough administrative reform at this stage would have shaken the foundations of the still fragile kingdom. Shalmaneser judged that the revolt had to be crushed and no one was better qualified to crush it than his energetic younger son. It took Shamshi-Adad V five years to subdue the twenty-seven cities wherein his brother had ‘brought about sedition, rebellion and wicked plotting’, and the remainder of his reign (823 – 811

B.C

.) to assert his authority over the Babylonians and the vassal rulers of the mountainous north and east, who had taken advantage of the civil war to shake off the Assyrian ‘protection’ and to withhold their tribute.

1

In the end, peace and order were restored, but no drastic changes were made in the central and provincial governments, and the malaise persisted giving rise, in the course of the following years, to other major or minor outbreaks of violence. This permanent instability affecting the infrastructure of the State, combined with other factors such as the lack of youth and slackness of some of Shamshi-Adad's successors and the ever-growing part taken by the rival kingdom of Urartu in

Near Eastern politics, accounts for the temporary weakness of Assyria during the first half of the eighth century

B.C

.

Assyrian Eclipse

Shamshi-Adad's son, Adad-nirâri III (810 – 783

B.C.

), was very young when his father died, and for four years the government of Assyria was in the hands of his mother Sammuramat – the legendary Semiramis. How this queen, whose reign has left hardly a trace in Assyrian records,

2

acquired the reputation of being ‘the most beautiful, most cruel, most powerful and most lustful of Oriental queens’

3

is a most baffling problem. The legend of Semiramis, as told in the first century

B.C.

by Diodorus Siculus

4

– who drew his material from the now lost

Persica

of Ctesias, a Greek author and physician at the court of Artaxerxes II (404 – 359

B.C.

) – is that of a manly woman born of a Syrian goddess, who became queen of Assyria by marrying Ninus, the mythical founder of Nineveh, founded Babylon, built astonishing monuments in Persia, conquered Media, Egypt, Libya and Bactria, conducted an unsuccessful military expedition in India and turned into a dove on her death. This legend contains many ingredients, including a possible confusion with Naqi'a/ Zakûtu (the wife of Sennacherib, who supervised the reconstruction of Babylon destroyed by her husband), as well as reminiscences of the conquests of Darius I, of the Indian war of Alexander the Great, and even of the Achaemenian court with the terrible queen-mother Parysatis. Semiramis also shares some traits with Ishtar as a war goddess who, like her, destroyed her lovers. At first sight, all this has nothing to do with what we know of Adad-nirari's mother. Yet both Herodotus and Berossus,

5

who said very little about Semiramis, have indirectly made it clear that she and Sammuramat were one and the same person. Where, then, is the link between the two women? The whole story has a strong Iranian flavour. Perhaps Sammuramat did something which greatly surprised and impressed the Medes (she might have led a battle against them), and her prowess

was transmitted through generations, distorted and embroidered, by Iranian story-tellers, until they reached the ears of Ctesias. But this, like other hypotheses, cannot be substantiated. Presented in many forms, Diodorus's account of the Semiramis legend has met with an enormous success, notably in Western Europe, until the beginning of this century. And thus, by an ironical trick of fate the memory of the virile Assyrian kings has passed to posterity under the guise of a woman.

As soon as he was of age to perform his royal duties, Adad-nirâri displayed the qualities of a capable and enterprising monarch.

6

In his first year of effective reign (806

B.C.

) he invaded Syria and imposed tax and tribute upon the Neo-Hittites, Phoenicians, Philistines, Israelites and Edomites. Succeeding where his grandfather had failed, he entered Damascus and received from Ben-Hadad III ‘his property and his goods in immeasurable quantity’.

7

Similarly, the Medes and Persians in Iran were, in the emphatic style of his royal inscriptions, ‘brought in submission to his feet’, while ‘the kings of the Kaldû, all of them’ were counted as vassals. But these were mere raids and not conquests. The spasmodic efforts of this true offspring of Shalmaneser III bore no fruit, and his premature death marks the beginning of a long period of Assyrian decline.

Adad-nirâri had four sons who reigned in succession. Of the first, Shalmaneser IV (782 – 773

B.C

.), very little is known, but his authority seems to have been singularly limited, for his commander-in-chief, Shamshi-ilu, in an inscription found at Til-Barsip (Tell Ahmar) boasts of his victories over the Urartians without even mentioning the name of his master, the king – a fact unprecedented in Assyrian records.

8

The reign of the second son, Ashur-dân III (772 – 755

B.C

.), was marked by unsuccessful campaigns in central Syria and Babylonia, an epidemic of plague and revolts in Assur, Arrapha (Kirkuk) and Guzana (Tell Halaf) – not to mention an ominous eclipse of the sun. It is this eclipse, duly recorded in the

limmu

list and which can be dated June 15, 763

B.C

., which served as a basis of Mesopotamian chronology in the first millennium (see page

25

).

As for the third son, Ashur-nirâri (754 – 745

B.C

.), he hardly dared leave his palace and was probably killed in a revolution which broke out in Kalhu and put upon the throne Tiglathpileser III,

9

a man whose membership of Adad-nirâri's family remains controverted and who might have been a usurper.

Thus for thirty-six years (781 – 745

B.C.

) Assyria was practically paralysed, and during that time the political geography of the Near East underwent several major or minor changes. Babylonia, twice defeated on the battlefield by Shamshi-Adad V but still independent, fell into a state of quasi-anarchy recalling the worst decades of the tenth century. In about 790

B.C.

for several years ‘there was no king in the country’, confessed a chronicle, while Eriba-Marduk (

c.

769

B.C.

) claimed as a great success a simple police operation against the Aramaeans who had taken some ‘fields and gardens’ belonging to the inhabitants of Babylon and Barsippa.

10

In Syria the Aramaean princes were too absorbed in their traditional quarrels to achieve anything like unity. Attacked on two fronts, humiliated by the Assyrians of Adad-nirâri and defeated by the Israelites of Ahab, the kings of Damascus lost their political ascendancy to the benefit first of Hama, then of Arpad (Tell Rifa‘at, near Aleppo), the capital-city of Bît-Agushi.

11

In Iran the Persians began migrating from the north to the south towards the Bakhtiari mountains,

12

and the Medes were left free to extend their control over the whole plateau. Around Lake Urmiah the Mannaeans (

Mannai

), a non-Indo-European people which excavations have shown to be far more civilized than one would have thought,

13

organized themselves into a small but solid nation. But the main development took place in Armenia, where in the course of the ninth and eighth centuries Urartu grew from a small principality on the shores of Lake Van to a kingdom as large and powerful as Assyria itself. Under Argistis I (

c.

787 – 766

B.C.

) it extended approximately from Lake Sevan, in Russian Armenia, to the present northern frontier of Iraq and from Lake Urmiah to the upper course of the Euphrates in Turkey. Outside the national boundaries were vassal states or

tribes which paid tribute to Urartu, acknowledged its suzerainty or were tied to it by military agreements. Such were the Cimmerians in the Caucasus, all the Neo-Hittite kingdoms of the Taurus (Tabal, Milid, Gurgum, Kummuhu) and the Mannai in Iran. Argistis's successor, Sardur II (

c.

765 – 733

B.C.

), also succeeded in detaching Mati'-ilu, King of Arpad, from the alliance he had just signed with Ashur-nirâri V and through Arpad the political influence of Urartu was rapidly spreading among the Aramaean kingdoms of northern Syria.

Old and recent excavations in Turkish and Russian Armenia – in particular at Toprak Kale (ancient Rusahina), near Van, and at Karmir Blur (ancient Teisbaini), near Erivan – have supplied us with copious information on the history and archaeology of the kingdom of Urartu.

14

Its main cities were built of stone or of mud bricks resting on stone foundations; they were enclosed in massive walls and dominated by enormous citadels where food, oil, wine and weapons were stored in anticipation of war. Urartian artisans were experts in metallurgy, and they have left us some very fine works of art displaying a strong Assyrian influence. All over Armenia numerous steles and rock inscriptions in cuneiform script and in ‘Vannic’ language – an offspring of Hurrian – bear witness to the heroism and piety of Urartian kings, while hundreds of tablets give us an insight into the social and economic organization of the kingdom, essentially based on vast royal estates worked by warriors, prisoners of war or slaves. The pastures of the Ararat massif and the fertile valley of the Arax river made Urartu a fairly rich cattle-breeding and agricultural country, but most of its wealth came from the copper and iron mines of Armenia, Georgia, Commagene and Azerbaijan, which it possessed or controlled.

The emergence of such a large, prosperous and powerful nation had a decisive influence on the history of Assyria. The ever-growing part assumed by Urartu in Near Eastern economics and politics, no less than its presence at the gates of Iraq, was for the Assyrians a source of constant worry but also a challenge. A series of unfortunate experiences under

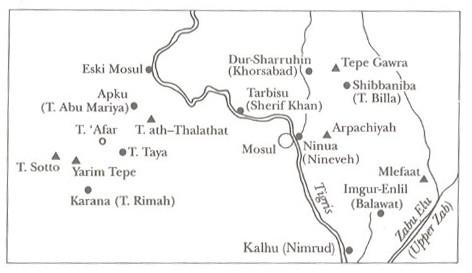

Principal sites in the vicinity of Mosul.

Shalmaneser IV had taught them that any attempt at striking a direct blow at Urartu in the present state of affairs would meet with failure. Before they could stand face to face with their mighty rivals they had to strengthen their own position in Mesopotamia and to conquer, occupy and firmly hold Syria and western Iran, those two pillars to Urartian dominion outside Armenia. The time of quick, easy, fruitful razzias was over. Assyria had no choice but to become an empire or perish.

Tiglathpileser III

Fortunately, Assyria found in Tiglathpileser III (744 – 727

B.C

.) an intelligent and vigorous sovereign who took a clear view of the situation and applied the necessary remedies. Not only did he ‘smash like pots’ – to use his own expression – the Syrian allies of Urartu and the Medes but he turned the subdued lands into Assyrian possessions, reorganized the Army and carried out the long-awaited administrative reform which gave Assyria the internal peace it needed. From every point of view Tiglath-pileser must be considered the founder of the Assyrian empire.

The administrative reform, gradually enforced after 738

B.C

. aimed at strengthening the royal authority and at reducing the excessive powers of the great lords. In Assyria proper the existing districts were multiplied and made smaller. Outside Assyria the countries which the king's victorious campaigns brought under his sway were, whenever possible or suitable, deprived of their local rulers and transformed into provinces. Each province was treated like an Assyrian district and entrusted to a ‘district lord’ (

bel pihâti

) or to a ‘governor’ (

shaknu

, literally: ‘appointed’) responsible to the king.

15

The countries and peoples who could not be incorporated in the empire were left with their own government but placed under the supervision of an ‘overseer’ (

qêpu

). A very efficient system of communications was established between the royal court and the provinces. Ordinary messengers or special runners constantly carried reports and letters sent by the governors and district-chiefs or their subordinates to the king and the court officials, and the orders (

amât sharri

, ‘king's word’) issued by the monarch. In some cases the king sent his personal representative, the

qurbutu

official, who reported on confidential affairs and often acted on his own initiative. District-chiefs and province governors had large military, judicial, administrative and financial powers, though their authority was limited by the small size of their charge and by the constant interference of the central government in almost every matter. Their main task was to ensure the regular payment of the tribute (

madattu

) and of the various taxes and duties to which Assyrians and foreigners alike were subjected, but they were also responsible for the enforcement of law and order, the execution of public works and the raising of troops in their own district. The last-mentioned function was of considerable importance to the motherland. Formerly, the Assyrian Army was made up of crown-dependents doing their military services as

ilku

(see page 206) and of peasants and slaves supplied by the landlords of Assyria and put at the king's disposal for the duration of the annual campaign. To this army of conscription, Tiglathpileser III added a permanent army

(kisir sharruti, ‘bond of kingship’) mainly formed of contingents levied in the peripheral provinces. Some Aramaean tribes, such as the

Itu

’ provided excellent mercenaries. Another novelty was the development of cavalry as opposed to war-chariots. This change was probably due to the frequency of battles in mountainous countries against people like the Medes who utilized mostly horsemen.

16

Another of Tiglathpileser's initiatives was the practice of mass-deportation. Whole towns and districts were emptied of their inhabitants, who were resettled in distant regions and replaced by people brought by force from other countries. In 742 and 741

B.C

., for instance, 30,000 Syrians from the region of Hama were sent to the Zagros mountains, while 18,000 Aramaeans from the left bank of the Tigris were transferred to northern Syria. In Iran in 744

B.C

. 65,000 persons were displaced in one single campaign, and another year the exodus affected no less than 154,000 people in southern Mesopotamia.

17

Such pitiful scenes are occasionally depicted on Assyrian bas-reliefs: carrying little bags on their shoulders and holding their emaciated children by the hand, long files of men walk with the troops, while their wives follow in carts or riding on donkeys or horses. A pitiful and no doubt partially real spectacle, but deliberately intensified for propaganda purposes, for while one of the aims of deportation was to punish rebels or prevent rebellions, it also had other objectives: to uproot what would now be called ‘national feelings’ – i.e. fidelity to local gods, ruling families and traditions; to fill new towns on the borders, in conquered countries and in Assyria proper; to repopulate abandoned regions and develop their agriculture; to provide the Assyrians not only with soldiers and troops of labourers who would build cities, temples and palaces, but also with craftsmen, artists and even scribes and scholars.

18

We know from the royal correspondence that provincial governors were told to ensure that the deportees and their military escort would be well treated, supplied with food (and in at least one case, with shoes!) and protected against any harm. We also know that

many of these displaced persons soon became used to new horizons and remained faithful to their new masters, and that some of them were given important posts in the imperial administration. The deportees were not slaves: distributed through the empire as needs arose, they had no special status and were simply ‘counted among the people of Assyria’, which means that they had the same duties and rights as original Assyrians. This policy of deportation – mainly from Aramaic-speaking areas – was pursued by Tiglathpileser's successors, and the number of persons forcibly removed from their home during three centuries has been estimated at four and a half million. It has largely contributed to the ‘Aramaization’ of Assyria, a slow but almost continuous process which, together with the internationalization of the army, probably played a role in the collapse of the empire.

The campaigns of Tiglathpileser III bear the imprint of his methodical mind.

19

First, an expedition in southern Iraq ‘as far as the Uknû river (Kerkha)’ relieved Babylon from the Aramaeans, pressure and reminded Nabû-nâsir that the King of Assyria was still his protector. As usual, ‘pure sacrifices’ were offered to the gods in the sacred cities of Sumer and Akkad, from Sippar to Uruk. Then Tiglathpileser attacked Syria or, more precisely, the league of Neo-Hittite and Aramaean princes led by Mati'-ilu of Arpad, who obeyed Sardur III, the powerful King of Urartu. Sardur rushed to help his allies, but he was defeated near Samsat, on the Euphrates, and fleeing ignominiously on a mare, ‘escaped at night and was seen no more’. Arpad, besieged, resisted for three years, finally succumbed and became the chief town of an Assyrian province (741

B.C.

). In the meantime a victorious campaign against Azriyau, King of Ya'diya (Sam'al), and his allies of the Syrian coast resulted in the annexation of north-western Syria, and probably Phoenicia (742

B.C.

). Numerous princes of the neighbourhood took fright and brought presents and tribute. Among them were Rasunu (Rezin), King of Damascus, Menahem, King of Israel,

20

and a certain Zabibê, ‘Queen of the Arabs’. In all probability, the starting-point of

the Syrian campaigns was Hadâtu (modern Arslan Tash), between Karkemish and Harran, where archaeological excavations have unearthed one of Tiglathpileser's provincial palaces, an elaborate building strikingly similar in layout to Ashurnasirpal's palace in Nimrud, though smaller. Near the palace a temple dedicated to Ishtar has yielded interesting pieces of sculpture, and in another building were found sculptured panels of ivory which once decorated the royal furniture of Hazael, King of Damascus, taken as booty by Adad-nirâri III.

21

Having thus disposed of the Syrian vassals of Urartu, Tiglath-pileser turned his weapons towards the east (campaigns of 737 and 736

B.C

.). Most of the central Zagros was ‘brought within the borders of Assyria’, and an expedition was launched across the Iranian plateau, in the heart of the land occupied by ‘the powerful Medes’, as far as mount Bikni (Demavend) and the ‘salt desert’, to the south-west of Teheran. Never before had an Assyrian army been taken so far away in that direction. The scanty remains of another of Tiglathpileser's provincial palaces found at Tepe Giyan, near Nihavend and a stele recently discovered in Iran, testify to the reality of the campaigns and to the interest taken by the king in Iranian countries.

22

Later (probably in 735

B.C

.) an attack was organized directly against Urartu, and Sardur's capital Tushpa (Van) was besieged, though without success.

In 734

B.C

. Tiglathpileser returned to the Mediterranean coast where the situation was anything but peaceful. Tyre and Sidon were restless because of the restrictions imposed by the Assyrians on the export of timber to Philistia and Egypt; the troops had to intervene and made ‘the people crawl with fear’.

23

Still worse, an anti-Assyrian coalition comprising all the kingdoms of Palestine and Trans-Jordania had been organized by the Philistine rulers of Ascalon and Gaza. Tiglathpileser himself crushed the rebels. The Prince of Ascalon was killed in action; the ‘man of Gaza’ fled like a bird to Egypt; Amon, Edom, Moab and Judah, as well as another queen of the Arabs called Shamshi paid tribute. Two years later Ahaz, King of

Judah, pressed by Damascus and Israel, called the Assyrians to the rescue. Tiglathpileser took Damascus, annexed half of Israel and established Hoshea as king in Samaria.

24

Meanwhile, a series of

coups d'etat

had taken place in southern Iraq, following the death of Nabû-nâsir, in 734

B.C.

When the Aramaean chieftain Ukin-zêr claimed the Babylonian throne (731

B.C

.) the Assyrians tried to persuade the citizens of Babylon to rise against him and promised tax-exemption to any Aramaean who would desert from his chief. But after diplomacy had proved useless Tiglathpileser sent his troops against the usurper who was killed, together with his son, and decided to govern Babylonia himself. In 728

B.C

. he ‘took the hand of Bêl (Marduk)’ during the New Year Festival and was proclaimed King of Babylon under the name of Pulû. The following year he died or, to use the Babylonian expression, ‘he went to his destiny’.