Ancient Iraq (8 page)

CHAPTER 4

The story of the passage from Neolithic to History, from the humble villages of the Zagros foothills to the relatively large and highly civilized Sumerian cities of the lower Tigris–Euphrates valley cannot be told in full detail because our information, though rapidly progressing, remains imprecise and patchy. Yet each new prehistoric

tell

excavated, each buried city dug down to the virgin soil, confirms what forty years of archaeological research in Iraq already suggested: the Sumerian civilization was never imported ready-made into Mesopotamia from some unknown country at some ill-defined date. Like all civilizations – including ours – it was a mixed product shaped by the mould into which its components were poured over many years. Each of these components can now be traced back to one stage or another of Iraqi prehistory, and while some were undoubtedly brought in by foreign invasion or influence, others had roots so deep in the past that we may call them indigenous. In addition, excavations conducted at an ever increasing pace in Iran, Syria, Palestine and Turkey at the same time as in Iraq have thrown considerable light on the interplay of Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures in the Near East and have supplied enough comparative material and radiocarbon dates to draw up a rough, tentative chronological scale along the six divisions of Mesopotamian proto-history:

| c . 5800 – 5500 B.C. |

| c . 5600 – 5000 B.C . |

| c . 5500 – 4500 B.C. |

| c . 5000 – 3750 B.C . |

| c . 3750 – 3150 B.C. |

| c . 3150 – 2900 B.C. |

Each of these periods is characterized by a distinct cultural assemblage and has been named after the site, not necessarily the largest nor even the most representative, where this assemblage was first identified.

As will be seen, the areas covered by these cultures vary from one period to the other; moreover, cultures long thought to be successive are in fact contemporaneous or at least overlapping, and within each period there is room for a variety of regional and interesting subcultures. The above divisions therefore, are somewhat artificial, but they provide a convenient framework into which can be fitted the changes that occurred during those three millennia when Mesopotamia was pregnant, so to speak, with Sumer.

1

The Hassuna Period

The site type for this period is Tell Hassuna, a low mound thirty-five kilometres south of Mosul, excavated in 1943 – 4 by the Iraqi Directorate of Antiquities under the direction of Seton Lloyd and Fuad Safar.

2

There, resting on the virgin soil, were coarse pottery and stone implements suggestive of a Neolithic farming community living in huts or tents, for no trace of building was found. Overlying this primitive settlement, however, were six layers of houses, progressively larger and better built. In size, plan and building material these houses were very similar to those of present-day northern Iraqi villages. Six or seven rooms were arranged in two blocks around a courtyard, one block serving as living quarters, the other as kitchen and stores. The walls were made of pressed mud, the floors paved with a mixture of clay and straw. Grain was kept in huge bins of unbaked clay sunk into the ground up to their mouths, and bread was baked in domed ovens resembling the modern tanur. Mortars, flint sickle-blades, stone hoes, clay spindle-whorls and crude clay figurines of naked and apparently seated women were present. Large jars found inside the houses contained the bones of deceased children accompanied by tiny cups and pots for after-life refreshment while, strangely enough, much liberty

seems to have been taken with the disposal of adult skeletons piled up in the corner of a room, thrown into clay bins ‘without ceremony’ or buried in cist graves without the usual funerary gifts. The few skulls that have been studied belong, like those from Byblos and Jericho, to a ‘large-toothed variety of the long-headed Mediterranean race’, which suggests a unity of population throughout the Fertile Crescent in late Neolithic times.

3

The pottery discovered at Hassuna has been divided into two categories called ‘archaic’ and ‘standard’. The

archaic ware

ranges from level Ia, at the bottom of the tell, to level III and is represented by: (1) tall, round or pear-shaped jars of undecorated coarse clay; (2) bowls of finer fabric varying in colour from buff to black according to the method of firing and ‘burnished’ with a stone or bone, and (3) bowls and globular jars with a short, straight neck, sparingly decorated with simple designs (lines, triangles, cross-hatchings) in fragile red paint and also burnished. The Hassuna

standard ware

, predominant in levels IV to VI, is made up of the same painted bowls and jars and the designs are very similar, but the paint is matt brown and thicker, the decoration more extensive and executed with greater skill. A number of vessels are almost entirely covered by shallow incisions, and some are both painted and incised.

While the archaic pottery has several traits in common with that found in the deepest layers of Turkish (Sakçe Gözü, Mersin), Syrian (Kerkemish, ‘Amuq plain) and Palestinian (Megiddo, Jericho) sites, the standard pottery seems to have developed locally

4

and is distributed over a relatively small area of northern Iraq. Sherds of Hassuna ware can be picked up on the surface of many unexcavated mounds east and west of the Tigris down to Jabal Hamrin, and complete specimens have been found in the lowest levels of Nineveh, opposite Mosul, at Matarrah,

5

south of Kirkuk and at Shimshara

6

in the Lower Zab valley. They were also present throughout the thirteen levels of mound 1 at Yarim Tepe,

7

near Tell ‘Afar, associated

with the remains of square or round houses, with tools and weapons of flint and obsidian, with pieces of copper ore and a few copper and lead ornaments, with small seated clay figurines and with minute stone or clay discs with a loop at the back, engraved with straight lines or criss-cross patterns. These objects, probably worn on a string around the neck, may have been impressed as a mark of ownership on lumps of clay fastened to baskets or to jar stoppers, in which case they would represent the earliest examples of the stamp-seal, and the stamp-seal is the forerunner of the cylinder-seal, a significant element of the Mesopotamian civilization. Some authors, however, regard them, at least in this period, as mere amulets or ornaments.

Forty-eight kilometres due south of Yarim Tepe, at the limit of the rain-fed plain and the desert of Jazirah, lies Umm Dabaghiya, excavated by Diana Kirkbride between 1971 and 1973.

8

Umm Dabaghiya was a small settlement, a simple trading post where nomads from the desert brought the onagers and gazelles they had hunted to be skinned, the raw hides being later sent elsewhere to be tanned. Related by its coarse and painted pottery to the archaic levels of Hassuna but most probably older, the site has many distinctive and strangely sophisticated features. For instance, the floors of the houses are often made of large clay slabs which announce the moulded bricks of later periods; floors and walls are carefully plastered with gypsum and frequently painted red, and in one building were found fragments of frescoes representing an onager hunt, a spider with its eggs and perhaps flying vultures. Several houses contained alabaster bowls beautifully carved and polished. Predominant among the clay vessels are bowls and jars with ‘applied decoration’, i.e. small figurines of animals and human beings stuck on the vessels before firing. Other sites representative of this Hassunan subculture are Tell Sotto and Kül Tepe,

9

near Yarim Tepe, and mound 2 at Tulul ath-Thalathat,

10

in the same Tell ‘Afar area. Not unexpectedly for places lying on the trade routes to the west and north-west, some

Caption

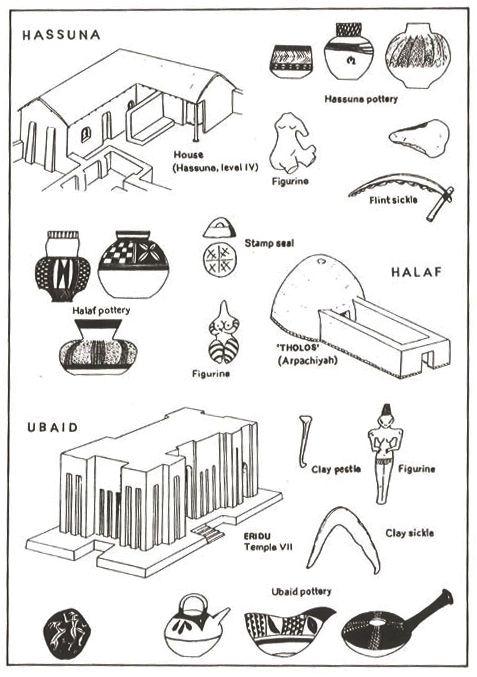

Buildings, potteries, figurines, seals and tools characteristic of the Hassuna, Halaf and Ubaid periods.

elements of the ‘Umm Dab culture’, such as plastered floors and arrow-heads, point to Syria (Buqras on the Euphrates and even Ras Shamra and Byblos), whilst the red and frescoed walls are reminiscent of contemporary Çatal Hüyük in remote Anatolia.

The Samarra Period

In the upper levels of Hassuna, Matarrah, Shimshara and Yarim Tepe the Hassuna ware is mixed with, and gradually replaced by, a much more attractive pottery known as

Samarra ware

because it was first discovered, in 1912 – 14, in a prehistoric cemetery underneath the houses of the medieval city of that name, famous for its spiralled minaret.

11

On the pale, slightly rough surface of large plates, around the rim of carinate bowls, on the neck and shoulder of round-bellied pots, painted in red, dark-brown or purple, are geometric designs arranged in neat, horizontal bands or representations of human beings, birds, fish, antelopes, scorpions and other animals. The motifs are conventionalized, but their distribution is perfectly well balanced and they are treated in such a way as to give an extraordinary impression of movement. The people who modelled and painted such vessels were undoubtedly great artists, and it was long thought that they had come from Iran, but we now know that the Samarra ware was indigenous to Mesopotamia and belonged to a hitherto unsuspected culture which flourished in the middle Tigris valley during the second half of the sixth millennium

B.C

.

This culture was revealed in the 1960s by the Iraqi excavations at Tell es-Sawwan, a low but large mound on the left bank of the Tigris, only eleven kilometres to the south of Samarra.

12

The inhabitants of Tell es-Sawwan were peasants like their Hassunan ancestors and used similar stone and flint tools, but in an area where rain is scarce they were the first to practise a primitive form of irrigation agriculture, using the Tigris floods to water their fields and grow wheat, barley and

linseed.

13

The yield must have been substantial if the large and empty buildings found at various levels were really ‘granaries’ as has been suggested. The central part of the village was protected from invaders by a 3-metre-deep ditch doubled by a thick, buttressed mud wall. The houses were large, very regular in plan, with multiple rooms and courtyards, and it must be noted that they were no longer built of pressed mud, but of large, cigar-shaped mud bricks plastered over with clay or gypsum. A thin coat of plaster covered the floors and walls. Apart from numerous pots and plates of coarse or fine Samarra ware, these houses contained exquisite, translucent marble vessels. The bodies of adults, in a contracted position and wrapped in matting coated with bitumen, and of children, placed in large jars or deep bowls, were buried under the floors, and it is from these graves that have come the most exciting finds in the form of alabaster or terracotta statuettes of women (or occasionally men) squatting or standing. Some of the clay statuettes have ‘coffee-bean’ eyes and pointed heads that are very similar to those of the Ubaid period figurines, whilst other clay or stone statuettes have large, wide-open eyes inlaid with shell and bitumen and surmounted by black eyebrows, that are ‘astonishingly reminiscent of much later Sumerian technique’.

14

Could the Samarran folk be the ancestors of the ‘Ubaidians’ and even perhaps of the Sumerians?

So far, no other settlement comparable to Tell es-Sawwan has been excavated,

15

but apart from copies or imports in Baghuz, on the middle Euphrates, and Chagar Bazar, in central Jazirah, the Samarra pottery has been found in a limited but fairly wide area along the Tigris valley, from Nineveh to Choga Mami near Mandali, on the Iraqi–Iranian border.

16

In the latter site, where canal-irrigation was practised, not only do we find statuettes resembling the ‘coffee-bean’-eyed statuettes of Sawwan, but the Samarra ware seems to have developed locally into new ceramic types (called ‘Choga Mami Transitional’) similar to the Eridu and Hajji Muhammad wares of southern Iraq, themselves considered as early forms of the Ubaid

pottery.

17

This unexpected discovery might provide the beginning of an answer to our question.