And Berry Came Too

And Berry Came Too

First published in 1936

© Estate of Dornford Yates; House of Stratus 1936-2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The right of Dornford Yates to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

This edition published in 2011 by House of Stratus, an imprint of

Stratus Books Ltd., Lisandra House, Fore Street, Looe,

Cornwall, PL13 1AD, UK.

Typeset by House of Stratus.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library and the Library of Congress.

| | EAN | | ISBN | | Edition | |

| | 1842329634 | | 9781842329634 | | Print | |

| | 0755126823 | | 9780755126828 | | Kindle | |

| | 075512703X | | 9780755127030 | | Epub | |

This is a fictional work and all characters are drawn from the author’s imagination.

Any resemblance or similarities to persons either living or dead are entirely coincidental.

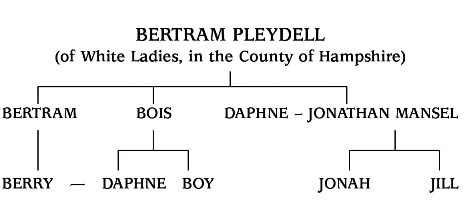

Born ‘Cecil William Mercer’ into a middle class Victorian family with many Victorian skeletons in the closet, including the conviction for embezzlement from a law firm and subsequent suicide of his great-uncle, Yates’ parents somehow scraped together enough money to send him to Harrow.

The son of a solicitor, he at first could not seek a call to the Bar as he gained only a third class degree at Oxford. However, after a spell in a Solicitor’s office he managed to qualify and then practised as a Barrister, including an involvement in the Dr. Crippen Case, but whilst still finding time to contribute stories to the

Windsor Magazine

.

After the First World War, Yates gave up legal work in favour of writing, which had become his great passion, and completed some thirty books. These ranged from light-hearted farce to adventure thrillers. For the former, he created the

‘Berry’

books which established Yates’ reputation as a writer of witty, upper-crust romances. For the latter, he created the character

Richard Chandos

, who recounts the adventures of

Jonah Mansel

, a classic gentleman sleuth. As a consequence of his education and experience, Yates’ books feature the genteel life, a nostalgic glimpse at Edwardian decadence and a number of swindling solicitors.

In his hey day, and as testament to his fine writing, Dornford Yates’ work often featured in the bestseller list. Indeed,

‘Berry’

is one of the great comic creations of twentieth century fiction; the

‘Chandos’

titles also being successfully adapted for television. Along with Sapper and John Buchan, Yates dominated the adventure book market of the inter war years.

Finding the English climate utterly unbearable, Yates chose to live in the French Pyrenées for eighteen years, before moving on to Rhodesia (as was), where he died in 1960.

‘Mr Yates can be recommended to anyone who thinks the British take themselves too seriously.’ - Punch

‘We appreciate fine writing when we come across it, and a wit that is ageless united to a courtesy that is extinct’ - Cyril Connolly

To JILL

I have an old patch-box – the flapjack of yesterday – on which is written

VIRTUE IS THE FAIREST JEWEL THAT CAN ADORN THE FAIR.

As no one else that I know, you show forth these pretty words, for while you are lovely to look at, the steady light which belongs to your great, blue eyes would diminish any gem to be found in the Rue de la Paix.

It is the duty of a tradesman to consult the convenience of his customers, though it be to his own derision. For that reason alone I make bold to say that,

mutatis mutandis

, the action of this book may be presumed to have taken place during the summer which followed the first chapter of BERRY AND CO. and preceded the second chapter of that book.

DORNFORD YATES.

How the Knave Set Out for Cock Feathers,

and Berry Made an Acquaintance He Did Not Desire

Seated upon the terrace of the old grey house, I found myself wondering whether the precincts of White Ladies had ever seemed so fair.

The fantastic heat was over, the cool of the day was in, and a flawless sundown was having her gentle way. A flight of rooks freckled the painted sky; oak and elm and chestnut printed their fading effigies on grateful lawns; the air was breathless; sound, catching the magic, stole on the ear. The fragrance of a drenched flower bed rose from below the balustrade; the five green peacocks, new-washed, sparkled upon the low, yew wall from which they sprang; like some loudspeaker, the stately press of rhododendrons was dispensing a blackbird’s song; and, beyond the sunk fence, a comfortable order of haycocks, redolent of Aesop and Virgil, remembered a golden world.

A slim shape passed between tree-trunks, and an instant later our two-year-old Alsatian, surnamed the Knave, moved gracefully upon the scene. Full in the open he stopped, to stand, like any statue, surveying the rolling meadows that made the park. So for a long moment, the beau-ideal of sentinels, all eyes and nose and ears, discharged his fealty: then the fine head came round and he glanced at the house. Steadily we regarded each other. Presently I lifted a hand… As though a wand had been waved, the statue leaped into life, flashed to the rhododendrons, plucked a ball from their fringe and cantered towards the terrace, sabre-tail at the carry and good-humoured eyes alight with confidence.

As I rose to meet him, my cousin’s clear voice rang out.

“Boy, where are you? Boy!”

Before I could answer, my cousin sped out of the library on to the flags.

Jill has never grown up. Though she is more than twenty, she has the look and the way of a beautiful child. Her great, grey eyes and her golden hair are those of the fairy-tales. Who runs may read her nature – a lovely document.

Naturally forgetting all else, the Knave went bounding to meet her and touch her hand. She stooped to smile into his eyes. Then she lifted a troubled face.

“Oh, Boy,” she cried, “do come and do what you can. Berry says he won’t go tomorrow.” She caught at my arm. “And he simply must. I mean, it’s all been arranged – we’ve something on every day. And we can’t throw everything up just because it’s turned hot.”

“I’ll come,” said I. “One moment.”

I took her arm and turned again to the lawns and the pride of the spreading boughs and the sparkling yew. Then I pointed to the fabulous haycocks, each with his sugar-loaf shadow, rounding the scene.

“Were you calling me?” I said. “Or were you calling Boy Blue? He’s lying under that big one. …And the Queen of Hearts has just gone. Lean over the balustrade and you’ll smell her perfume. And a blackbird’s been singing to the peacocks. It’s only a matter of time – one day he’ll sound the note that’ll bring them to life. Some evening like this. And now can you blame Berry for hating to leave all this and go up to town?”

“I know, I know. I hate going. I can’t bear leaving it all. But I do want to go to Ascot, and – and – any way, it’s too late now. Everything’s all arranged.”

“All right, sweetheart,” said I. “I’ll do what I can.”

“I don’t believe you want to go.”

“I don’t,” said I. “I’m a man. I don’t want to have to dress up, and I’m much more comfortable here than I should be at any hotel. But I quite agree with you that it’s too late now. I’ve got to start now, and so has Berry. I don’t suppose he’s serious.”

“He is, Boy, really. I know by the look in his eyes.”

“Come,” said I, turning, “and let me see for myself.” Followed by the Knave, we passed through the cool of the house, across the drive and on to the lawn beyond.

My sister was sitting upright in an easy chair: finger to beautiful lip, she regarded her husband gravely, as one who is uncertain how to retrieve a position which one false move will make irretrievable. Six feet away, Berry lay flat upon the turf: his eyes were shut, and but for the cigarette between his lips he might have been asleep; by his side was a tankard capable of containing an imperial quart.

As we came up—

“They say,” said Berry, “that the hippopotamus—”

“Thank you,” said his wife. “If it’s anything like what you say they say about the rhinoceros—”

“I mean the rhinoceros,” said Berry. “They say—”

Before the storm of protest the rumour was mercifully withheld.

“Disgusting beast,” said Daphne. “Just because you don’t want to move—”

“My object,” said Berry, “was to divert your attention. Continued concentration upon the unattainable is bad for the brain.”

I put in my oar.

“You can’t back out now,” I said bluntly.

Berry opened his eyes and rolled on to his side.

“And Satan came also,” he said. “Never mind. Who’s ‘backing out’ of what?”

“No one,” said I. “It’s too late. You know it as well as I.”

My brother-in-law sat up.

“Look here,” he said. “At great personal inconvenience I had arranged to accompany those I love upon a jaunt or junket to the metropolis. I now find that owing to the large anticyclone, unexpectedly stationary over Europe, my health will prove unequal to the projected sacrifice. Except that this discovery has caused me much pain, there’s really no more to be said,” and, with that, he shrugged his shoulders, picked up his tankard and drank deep and mournfully.

I took my seat upon the lawn.

“And what about me?” I said. “D’you think I’m going to enjoy it?”

“I’ve no idea,” said Berry. “I’ve never considered the point.” He glanced at his wrist. “Let’s see. At this hour tomorrow you will have already dined and will be walking sharply in the direction of the car park.” He raised his eyebrows. “I’m not sure you won’t be running – if you’re to be in time for the second act.”

I set my teeth.

“You solemnly undertook to—”

“I know,” said Berry. “I know. But this heat is an Act of God. In view of that, the contract is null and void.”

“Rot,” said I. “Supposing I said the same.”

“If you had any sense, you would – all of you. But perhaps you can do without sleep. Unhappily, I can’t. The last heat-wave in London shortened my life. Why? Because I rose in the mornings more dead than alive. And there’s the rub. But for the nights, I’d do it. But for the nights, I’d strut and fret at Ascot, dine in broad daylight and stagger off to the play. But go without sleep I will not. Damn it, it can’t be done. If you’re to live like that – ‘to grunt and sweat under a weary life,’

you – must – have – sleep

.”

Here he drank again with great violence and then lay back upon the turf.

There was a little silence – which I employed in wondering how to attack a contention with which I entirely agreed. Then I caught Daphne’s eye and turned again to the breach.

“That’s so much wash,” I said boldly.

“So much what?” said Berry.

“Wash,” said I. “And you know it. I don’t say Town will be pleasant, but that’s not a good enough reason for chucking everything up. Besides, this heatwave will pass.”

“Certain to,” murmured Berry. “That’s why they call them waves.”

A step on the gravel behind us made me look round.

Then—

“Excuse me, sir,” said the butler, “but the ice-machine has just failed. There’s ice enough for tonight, sir, but I thought I should tell you at once.”

“All right, Falcon,” I said. “I’ll be along…later on.”

“Very good, sir.”

As I lay back, my brother-in-law sat up.

“What are you waiting for?” he said. “As imitation electrician to this establishment—”

“What does it matter?” I murmured. “We’re going away.”

“And what about me?”

I shrugged my shoulders and stared at the reddening sky.

“I’ve no idea,” said I. “I’ve never considered the point.” My brother-in-law choked. “There is, however, a real electrician at Brooch. It’s too late to telephone now: and tomorrow is Saturday; but he’ll come on Monday all right, if you put in an SOS.”

“On Monday?” screamed Berry. “

Monday?

Sixty hours of this weather without any ice!”

“If you put the butter—”

“Look here,” said Berry shakily. “If you tell me where to put the butter, I shall suggest an even more appropriate depository for the pineapple chunks.” He looked round wildly. “I suppose the idea is blackmail. ‘Go to London, or stay here without any ice.’”

“Well, it serves you right,” said Jill. “If…”

Berry rose to his feet, clasped his head in his hands and took a short walk. Plainly concerned at his demeanour, the Knave accompanied him.

As the two passed out of earshot—

“We’ve got him,” breathed Daphne, excitedly. “Well done, Boy.”

“Thank Fate and Falcon,” said I. “They played clean into my hands.”

Berry returned from his stroll, picked up his tankard and drank what was left of his beer. Then he turned to his wife.

“Do you subscribe to this treachery?”

“If it’s going to get you to Town.”

“I see. You’ll allow that long-nosed leper to—”

“I will,” said Daphne cheerfully.

With a manifest effort, her husband controlled his voice.

“My love,” he said, “I beg you.” He put out a beseeching hand. “Think of your health.”

“My health?”

“Your blessed health,” said Berry piously. “I had hoped by my withdrawal to dissuade you from putting in peril—”

“You wicked liar,” said Jill.

“Remove that child,” said Berry, excitedly. “Take her away and hear her catechism. Teach her how to spell ‘reverently.’ Just because I venture to hint that only a half-baked baboon who was bent upon self-destruction would choose this moment to—”

The sudden brush of tyres upon gravel cut the philippic short and switched our eyes to the drive.

A moment later Jonathan Mansel, Jill’s brother, brought his Rolls to rest twenty paces away.

“Jonah?” cried Jill, and put a hand to her head. Her surprise was natural. Her brother lived in Town, and was to have dined with us the following day. And now he had come to us, when we should have gone to him.

We watched him leave the car and Carson, his servant, slip into the driver’s seat.

As he reached the lawn, he nodded.

“Wrong way round,” he said shortly.

“What’s the matter?” said Daphne, rising.

“Plague broken out?” said Berry.

Jonah kissed his sister and then sat down on the sward. “No air in London,” he said. “I’ve had no sleep for two nights.”

There was an electric silence.

Then—

“Choose your drink,” said Berry, brokenly. “Only say the word. I’ll mix it myself – all of them. What about a spot of Moselle? And the glass washed out with curaçao, before it goes in?”

“Shandy-gaff, please,” said Jonah. “About a third to two-thirds. You might bring a jug.”

Shouting for Falcon, Berry ran to the house.

Hitherto speechless with horror, Daphne and Jill let out a wail of dismay.

“But, Jonah…”

“It’s quite all right,” said Jonah, producing a pipe. “I’ve rooms for us all at Cock Feathers. Used to be Amersham’s place, but it’s now an hotel. Fine old house, twenty minutes from Ascot and just about forty from Town.”

I am prepared to wager that when the sixth Lord Amersham parted with his seat, Cock Feathers, it went to his heart to dispose of so lovely a thing. A sixteenth-century manor, in ‘specimen’ condition within and without, perfectly lighted and warmed and cunningly brought into line with the luxury mansion of today is not to be sneezed at: but add that its priceless ceilings have rung with the hearty laughter of Henry the Eighth, that Anne Boleyn has strolled in its formal garden and a baby Queen Elizabeth clambered up to its windows and played with her toys before its hearths – that these things are matters of fact and not of argument, and you will see that, standing in its broad meadows and squired by timber planted when it was built, Cock Feathers has that to offer which is not often for sale.

We had seen its glory by day: and now as we stole up the drive to find it sleeping beneath a peerless moon, I know that I blessed the foresight which Jonathan Mansel had shown. The peace about us was absolute, the air abundant and cool: the noisy pageant of London seemed stuff of another age. Yet thirty-five minutes ago we had been subscribing to the revelry of a stifling nightclub.

Berry alighted, to inspire luxuriously. Then he glanced about him, and a hand went up to his head.

“It’s all coming back,” he said visionally. “I knew it would. Directly I saw this place, I knew I’d been here before.” He pointed a shaking finger. “Anne Boleyn was up at that window, laughing like blazes and clapping her pretty hands; and Henry the Eighth was down here, stamping holes in the flags. He’d just hit his head on the lintel, but she hadn’t seen that bit and thought he was going gay. And then he looked up and saw her… It was an awful moment – I think we all feared the worst. And then Wolsey dropped his orange, and his mule kicked him well and truly while he was picking it up. I still think he did it on purpose. Any way, the situation was saved. They heard the King’s laughter at Windsor – that’s twelve miles off.”

“And what did Wolsey do?” bubbled Jill.

“Rose to the occasion,” said Berry. “I can see him now. He just looked round: then he pointed to the mule, whose name was Spongebag.

‘Non

Spongebag,

sed

Shoelift,’ he said.”

Here the wicket-door was opened, and, Daphne and Jill alighting, Jonah drove off to the coach house to berth the Rolls beside his.

One by one, we entered – delicately. It was extremely easy to hit your head.

As I bowed to the presumptuous lintel—

“Captain Pleydell, sir?” said the night-porter.

“That’s right,” said I.

“I’ve a telephone message for you, sir.” He turned to a pigeon-hole. “Come through about ten o’clock.”

I glanced at the note. Then I called to the others and read the message aloud.

Very much regret to say the Knave cannot be found. Gave him his dinner myself at half past four, but has not been seen since. Respectfully suggest the dog may have gone off to find you.