Andie's Moon (12 page)

Authors: Linda Newbery

They all watched while Neil Armstrong collected samples of moon dust and rock. A few minutes later, Buzz Aldrin came carefully down the ladder, guided by Armstrong – bobbing like an inflated toy in the moon’s reduced gravity. And now the two were talking to each other: “Isn’t that something? Isn’t it fine?” It sounded so ordinary; they might have been on Brighton beach. Andie had expected them to say something more startling, something wise and wonderful. But what? Perhaps “Wow!” and “Unbelievable!” and “Isn’t that something?” were the best that could be done with words, when you saw something utterly astonishing. Perhaps a person standing on the moon wouldn’t quite be able to believe what they’d seen and done, till much later. Perhaps not ever.

Neil Armstrong aimed his camera at what he called “the panorama”, the view from where he stood – the surface of the moon, pale, flat, pockmarked. But it wasn’t Andie’s moon. She had the odd feeling that

her

moon was somehow more real. Part of her longed to go back there, by herself.

The two astronauts put up an American flag and posed beside it.

“That doesn’t seem right,” Sushila said. “It’s like they’re claiming the moon for America.”

“The plaque says

for all mankind

,” Kris pointed out.

“I know, so it ought to be an Earth flag. Or no flag at all.”

“An Earth flag! Now, that would be something,” agreed Sushila’s mother. “I can’t help thinking that all those billions of dollars this has cost would’ve been better spent on reducing poverty in Africa and India. It seems dreadful that people starve in Biafra while these colossal sums are spent on landing two men on the moon.”

“Shh, shh, here’s Richard Nixon.”

Now the President of the United States was speaking to the astronauts by telephone from the White House. “This certainly has to be the most historic phone call ever made,” he said. “For every American, this has to be the proudest thing of our lives, and for people all over the world.” It sounded like he was reading a speech. “Because of what you have done, the heavens have become a part of man’s world.”

“But they always have been,” said Ravi. “People have always looked at the stars, and tried to make sense of them.”

He immediately looked embarrassed at having said so much. A few moments later, when his mother went into the kitchen to bring in cakes and sweet pastries and coffee, he followed her out of the room, and didn’t come back. Andie guessed that he’d escaped to the attic. She was torn between carrying on watching the television, and following him outside to look at the real moon.

It was Kris who noticed next. “Where’s Ravi? I can’t believe he’s missing this!”

“Gone to bed?” Patrick said, yawning. “It’ll be hardly worth it if we stay up much longer.”

“If I know Ravi,” said Mr. Kapoor, “he’ll have gone up to the roof. He’s got a telescope now – his uncle gave it to him.”

“On the roof?” Mum looked puzzled. “How does he get up to the roof?”

Andie tried not to turn red.

“There’s a way out through the attic storeroom. It’s quite safe,” Mr. Kapoor told her. “You’ve been up there, I expect, Kris?”

“Sure,” Kris answered, then, to Andie, “How about now? I don’t think I’m going to bed at all. Coming?”

Andie followed her very quickly, before anyone could think of a reason why not.

It was already far too light for star-watching. Towards the east, along the river, the sky was pale mauvey-pink, streaked with faint cloud. The low moon was faint, silvery, two-thirds of it in shadow; present even when it appeared to dissolve into daylight. Although it was ridiculous to imagine she’d see the American flag staking its claim across a quarter of a million miles of sky, she felt reassured that the moon looked as pale and untroubled as it always had.

“Did you see them, Rav?” Kris called, as she and Andie emerged onto the walkway.

“Course! I waved at them, and they waved back.” But Ravi was removing the telescope from its mount, putting it back in its leather case.

“Hello, day.” Kris held out her arms. “It’s nice up here, isn’t it? I like the feel of the day starting up.”

“And not just any day,” said Ravi. “It’s Monday. Moon-day.”

“Happy Moonday! Hey, is this the first real Moonday? It might look just the same as any other Monday, but it’s not.”

Kris looked over the parapet. Andie and Ravi looked too, the three of them in a row, gazing down at Chelsea Walk, and beyond it to the Thames. Andie heard the hooter of a barge, the cooing of pigeons, traffic on the bridge, and a siren somewhere; she saw the leafy canopy of trees, the grass below; a dog out walking by himself, and strings of lights along the Embankment; she smelled the faintest tang of salt. It all felt fresh and brand new in the cool air of dawn.

She wanted to catch and keep this moment.

But I’ll always remember, she thought, even when I’m ancient and a grandmother. The day I stood on the roof with Kris and Ravi, and watched London wake up, and there were men on the moon.

Chapter Fifteen

The Slough of Despond

“MAN ON THE MOON” dominated the news. Andie saw the same photographs again and again: the boot-print, heavily shadowed; the Earth from the moon; the two astronauts by the American flag; and Neil Armstrong reflected in Buzz Aldrin’s helmet visor. The lunar module had successfully taken off from the surface and – amazingly – docked with the command module exactly as planned, and the first men on the moon were on their way back to Earth.

Andie went back to her own imagined landscapes, where the moon was silent and alone, not the focus of the world’s obsessive gaze. She painted the Sea of Tranquillity empty once more, with a blur of footmarks, and the prints left by the spidery lunar module; beyond, the powdery surface was unmarked by humans.

On Tuesday she went with Kris to the King’s Road, to deliver a batch of Marilyn’s jewellery to East of the Sun, West of the Moon. She hoped Zak wouldn’t be there – hadn’t he said he was only helping out a friend? But he was outside, hanging T-shirts on a rail. He said, “Hi, you guys,” mainly to Kris, then looked at Andie as if he recognized her from the shoplifting incident. All her family members, wherever they went, seemed to devote themselves to creating maximum embarrassment for her, Andie thought.

Kris handed over the box of jewellery to the sharp-faced blonde woman and spent a few minutes discussing which of Marilyn’s pieces were selling best. As they left the arcade, Zak, who was now at the till, said to Andie, “Tell Prue I got her message, would you? Tomorrow’s cool. Quarter to nine, tell her.”

“What’s that about?” Kris asked, out on the pavement.

“No idea.” Andie was baffled. “We went in there last week, and Prune, er, talked to Zak. I don’t know what else.”

“What, is she going out with him or something? That’s neat.”

Andie thought this most unlikely, but was reluctant to explain why. She’d cross-examine Prune about it later.

Much of the world might have been gazing at the moon, but the King’s Road was still the centre of its own universe: self-absorbed, inhabited by beautiful people with swishy hair and arty clothes. Where did they come from? Andie wondered. Where did they go to? Had they been bred specially from shop mannequins, or designed by the editors of

Honey

? Somehow, in the King’s Road, even the plainest people, simply by being there, managed to make themselves look like the last word in cool.

Walking its length in Kris’s company was at least less exhausting than with Prune, who wanted to dive into every shop and exclaim over every window display. Kris, though younger, had an air of having seen it all before, of being used to nothing else. It was Andie who wanted to stop and gaze, and who thought she glimpsed George Harrison in a passing taxi.

“It was

him

! I’m certain!”

“It wasn’t!”

“It was!”

With a twinge of regret, Andie knew that she’d miss this. Slough High Street couldn’t possibly match this daily parade of hipness and gorgeousness.

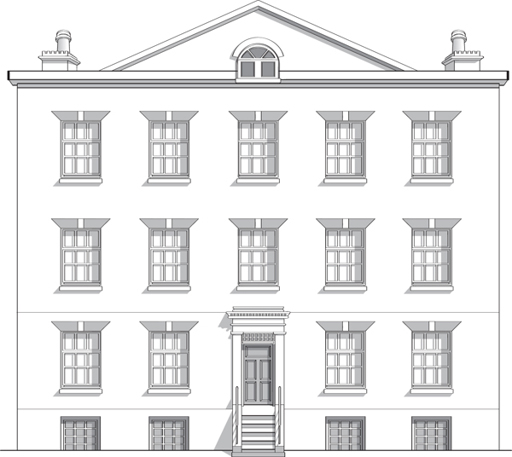

They were approaching the Town Hall. Standing squarely over the passers-by, the building made Andie think of a portly great-uncle with twirling moustaches, who had wandered by mistake into a disco. With its grand steps, pillared entrance and gilded clock, it looked surprised to find itself at the heart of fashion-conscious Chelsea. The gallery next door had a noticeboard outside: FASHIONS FOR THE SPACE AGE. EXHIBITION INSIDE.

“Hey, see this?” she called to Kris, who was about to walk on past.

They stopped to read. The poster gave details of a summer holiday competition, open to anyone under eighteen; entries were being displayed from now until the end of July.

“Shall we?”

“Sure, why not?”

They went inside. The gallery consisted of several rooms, one of which, light and airy, displayed the competition entries. Pictures and paintings were mounted on the walls, and on screens reaching across the middle. The work was of varying skill – some could easily have come from fashion magazines; some were clumsily drawn in coloured pencil or pastel. The concept of “The Space Age” had been given wide interpretation, from spacesuits like the ones the Apollo astronauts wore, to designs inspired by Mary Quant or Biba.

“Looks like fun,” Kris was saying. “You ought to have a go at this, Andie – it’s not too late, is it? Why not?”

Andie stopped dead, staring. There, on a screen in front of her, were three of her own fashion drawings – mounted on card, neatly labelled, each one signed in a flourishing hand by

Prue Miller.

“They’re cool,” said Kris. “See, you could do as well as that – Hey,

Prue Miller

! Is that your Prune? I didn’t know she was into drawing, as well?”

“She isn’t.” Andie’s voice came out strangled.

Kris raised her eyebrows. “They look pretty good to me.”

“But they’re

mine

! The ideas are hers, the clothes.

I

drew them – to cheer her up – but she never told me – the lying cow!”

Kris seemed to find this amusing. “Well, I guess you’ll be having words with her, later on.”

“You can say that again!”

“Do you think you could have your argument out on the street?” A woman’s face appeared around one end of the screen, and a curly-haired toddler ducked underneath to peer at the girls, round-eyed. “Some of us are trying to enjoy the exhibition.”

“Sorry.” Andie hadn’t realized there was someone else in the room. “But how

could

she?” she hissed at Kris. “Put

her

signature on

my

drawings! It’s fraud, that’s what it is!”

She stared at the drawings in indecision, half inclined to rip them off the display board. But part of her was

proud

to have work on show in an exhibition in the King’s Road, even if it was just a larky summer holiday thing. The cheek of Prune, though!

“It’d be worse,” Kris pointed out, “if she’d taken your paintings. Your moon pictures. I mean, these are good, but they’re not really

you,

like the others are

.”

Andie wouldn’t be pacified. It was still outrageous. It was practically

theft.

“May as well take a look at the rest, now we’re here,” said Kris.

The drawings and paintings passed before Andie’s eyes in a blur of colour and line. She was impatient to get home, and let out the pressure that was building up inside her till she felt jet-propelled with anger and indignation.

“Prune? Prune, you in?” she shouted, letting herself into the flat.

No answer. Typical of Prune not to be around when she was wanted. Now what?

Andie ran downstairs and out to the garden, looking for Kris. And there Prune was – on the swing, swaying gently back and forth.

“Prune? What are you doing?” Andie yelled.

Prune looked up vaguely. “Waiting for Sushila.”

“Oh. And then what are you doing? Going to look at the exhibition next to the Town Hall, by any chance?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” said Prune, but the pinking of her cheeks gave her away.

“Yes, you do. Three drawings signed by

Prue Miller.

Three of

my

drawings. Signed themselves, did they? Entered themselves for the competition?”

“Oh,” said Prune. “Those.”

“Yes,

those.

How could you do it, Prune? How could you be so sneaky? Why didn’t you

ask

?

”

“They were my ideas.” Prune looked at her defiantly. “You wouldn’t have done it otherwise. You only did the drawing.”

“

Only!

What do you mean,

only

?”

“Oh, don’t be so mean, Andie! You know how much I want to work in fashion. If I win that competition—”

“If

you

win it!” Andie humphed. “Some chance! Did you look at the other entries? There are loads better than yours – I mean

mine.

How could you be so sneaky, entering my drawings with your name on them! You didn’t even ask – didn’t think that we could

both

have entered – didn’t say a word!” She paused for breath, and relaunched. “That’s just typical of you! Whatever you want, you think you can help yourself – like that bangle, and the Biba dress—”