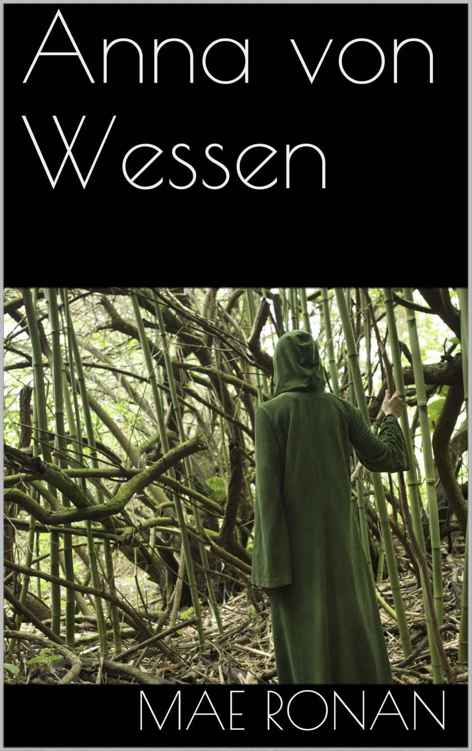

Anna von Wessen

Authors: Mae Ronan

Anna von Wessen

By Mae Ronan

I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord;

he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live:

and whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die.

– John 11:25-26

I hold another creed, which no one ever taught me, and which I seldom mention,

but in which I delight, and to which I cling; for it extends hope to all;

it makes Eternity a rest – a mighty home, not a terror and an abyss.

– Charlotte Brontë

Introduction

T

he world has been inhabited, for long centuries, by much more than ourselves. We are not alone; and we are not greatest.

They say that the first were Adam and Eve; and though we do not mean to counter that claim, we do mean to tell you – if we may be so bold – of

another

of the firstborn races. These were not exactly humans; but rather a combination of human and animal. They were called the Endai, or the wolf-people.

It should go without saying, since God made all living things, that God Himself was the Father of the wolf-people. Either before or after them – or perhaps alongside of them – came the humans, who lived apart from animals, and never even guessed that the wolf-people were their brothers. When the Endai were in human form, they called them family; but when they walked as wolves, they called them beasts, and saw nothing wrong in killing them. Never, then, was it possible for humans to be the kindred of the Endai. Always they were different; always they were separate.

In the beginning, there were the wolf-people, the humans, and the animals. There were flowers, and trees, and all things that grew under God’s hand. But later came the things that the Black One made – and these were the Lumaria, and the Narken. The Lumaria were forged in the pits of Hell by the hand of the Black One himself. They walked always in human form, and were immortal. Their gifts included teleportation and telepathy. They were also incredibly strong and swift; but they could not thrive upon normal sustenance. Naught but human flesh would serve as their food. When still they dwelt within the bounds of the underworld, they sated themselves with the discarded shells of the damned. But then they were sent aboveground, to the world which lay under Heaven; and they fell like a scourge upon humanity.

After the Lumaria came the Aurens – or the protectors. The Aurens were given great Power by the angels of Heaven, which was meant for the furtherance of goo

d, and the dispelling of evil; but there was one Auren who did the bidding of the Evil One, and was given as a result supreme might. With it she created the Narken, who once were ordinary men of a land called the Broken Earth. But they were cursed, and tainted with the blood of the fierce black wolves which dwelt in the dark forests, whereafter they became enormous, ugly beasts.

And yet, after a number of years, the Narken grew tired of being always feared and abhorred.

So one amongst them, whose name was Bru, undertook a mission to the underworld, to request the return of their human bodies from the one who had given Dain Aerca the magic which cursed them.

The Black One acquiesced, insofar as granting them the ability to revert to human form; but still he would not lift the curse, as he wished to keep them for himself. So Bru returned to the Narken with the gift of humanity – and from that day forward, his peop

le walked as both man and wolf, making them the second of the races which men call “werewolves.”

They were able, then, to come out of their dark and hidden recesses, and breathe the free air of the world. But never did the Lumaria establish a camaraderie with them; for neither race had any more reverence for, or even belief left in, the Black One. Each race, rather, considered itself supreme, and most powerful.

Therefore a war was declared between them.

This war has raged for long centuries. Even come the present day, it has not at all decreased in fervour. Many battles have been fought; and many deaths have occurred.

This account shall serve to portray events leading up to one of the most important of these battles: that which was fought at Castle Drelho in the summer of 2012.

Prologue

W

e begin our story in the year 1750. The largest clan of the Lumaria, at that time, dwelt in England; and their King lived in a great castle. His people numbered in the thousands, but his family consisted solely of his beloved daughter, Vaya Eleria.

In the year 1550, King Ephram and his mate, Vyra Iyenov, decided they wanted a child. The Lumaria, however, are incapable of delivering children; so, on a trip to Italy for a meeting of the Night Council, Ephram’s Queen chose the very most beautiful woman of her liking, and Ephram took her to be the mother of their child. As with all cases of Lumarian gestation, Clarisa Bartoli underwent great pain and torture, and finally died giving birth to Vaya. Her fate was a sad one; but by no means an uncommon one.

Vaya lived all her life as a Lumarian Princess. She was skilled in the art of war, and was leader of her father’s army. It was the task of this army to do one thing, and one thing only: and this thing was to kill the Narken.

On the eve of Vaya’s two-hundredth year, it was her father’s plan to make her Queen. Vyra had died nearly a hundred years before, in an attack on the castle – and Ephram thought it high time for his people to have a Queen once again. His love and esteem for Vaya were boundless. Never would he even have thought to take for himself another mate, and as a result to keep the Queenship from his daughter. So he went to great lengths and pains, to orchestrate an elaborate ceremony for marking the end of her second century.

Merely a month before the celebration, however, Ephram learnt a terrible secret. It seemed that his daughter, the very commander of the war against the Narken, was betrothed to one of the shape-shifters – a wolf named Krestyin.

Upon discovering this, Ephram was sickened with shame. Despite his great love for Vaya, he had no choice but to order her execution. So he stood, horrified, at the door of her death chamber – and rushed in at the very last moment, to stay the hand of the executioner. Then he shoved him out of the room, and finished the work himself.

After the thing was done, he fell down upon the floor, and lay for many hours beside Vaya’s body, until someone came finally to see about him.

Part the First

Episode I

I:

The Finding of Anna von Wessen

I

t was the balmy, breezy morning of June the seventeenth, 1936 – and Ephram was sailing in his great ship back to America. He had been the past two days in France, holding the annual meetings there with the Night Council. Last year it had been Russia; the year before, Spain . . .

He was eager to be home again, and away from the sea. He was in a sour mood when he rose from the berth in his cabin; so he went on deck to view the morning sky. And what should be the first thing he spotted, when he arrived there – but a little island just a few miles to the South, with a ship quite as large as his own, wrecked upon its coast?

He called to his Captain. That fellow showed himself quickly, jogging round from the starboard deck. “Yes, Master?” he inquired.

“Look there, Nim,” said Ephram, pointing towards the island. “Did you not see that before?”

“Yes, Master – I saw it.”

“And did you not think it worth mentioning?”

“I thought not that you would be interested, Master.”

“Well, I am. Bring me to that island.”

“Right away.”

Nim turned on his heel, and trotted towards the bow, where he gave directions to have the ship turned Southward. Shortly thereafter, they changed their course, and began to creep towards the island.

They dropped anchor about half a mile from the coast. Nim ordered for a dinghy to be lowered, and climbed down into it himself, so as to pilot Ephram the remainder of the distance. Ephram went to the front of the port deck, and leapt into the dinghy, where he sat on the little wooden bench, and gave Nim the command to proceed.

The crew watched from the ship, as the dinghy crawled towards the wreckage on the coast. Nim worked the oars deftly, and brought the little boat directly alongside the leaning ship. “Would you like to board, Master?” he asked.

“Yes,” Ephram answered.

Nim glided a little nearer, and jumped up onto the ship’s wobbling deck, where he tied the painter to the sturdy rail. “Whenever you’re ready, Master,” he said.

Ephram stood up, and followed Nim to the deck, where he looked all about him for a long moment.

“Would you like me to accompany you, Master?” asked Nim.

“You may do whatever you like,” said Ephram. “I’m going to have a look around.”

Nim stared after Ephram’s retreating back, wondering whether he should follow; but seeing as he had not been ordered to do so, he did not see the point. So he climbed back into the dinghy.

Ephram went on alone, indeed having forgotten all about his earlier desire to be home. Now he was merely curious; and so he went looking all round the abandoned ship, in search of something interesting.

Abandoned it surely was. There seemed not a soul to be found, either dead or alive. As he approached it, Ephram had looked with his sharp eyes upon the barren little island, too; and had seen no signs there of life new or old. So whither had the passengers fled?

The ship was in a state of chaos. Everywhere there was the clutter and debris of broken things. In several places there were even strange outlines smashed into the wood – not merely the result of slipping, stumbling feet, but perhaps that of many angry hands which pushed and shoved.

In spite of all this lovely mystery, Ephram grew bored after about a quarter of an hour’s survey. There were many questions here, that was true; but there were left not so much as ghosts to answer them. And questions without impending answers – or so Ephram had found, over the course of his long life – made for very poor entertainment. He prepared himself, then, to return to the deck; but the instant he had turned his back, his ear was met by the sound of crying. The crying of an infant.

Ephram looked back to the cabins, and began to retrace his steps. As the wailing grew louder, he glanced all about – but saw nothing.

His keen ears led him finally to the corner of the second cabin, where the very berth had been ripped from the wall. Straightaway he reached down; lifted the whole mess up off of the floor; and heaved it away. But still he could not mark anything out of place. So he listened more closely, and followed the sound to a little niche behind a thick, swinging plank at the bottom of the wall. There – twisted up in a coarse old blanket, and nearly blue in the face from screaming – was a small child.

Ephram stood looking down on it for a little, before he decided to pick it up. But when finally he did, he noticed a large bruise on its forehead, which dripped blood from the very centre. Its little body was thin and wasted.

Ephram looked for a long while into the child’s face, captivated by the expression on its pale, soft skin. It had stopped crying, since he took it in his arms. Now it looked up at him with wide eyes, its very small fist reaching to clutch at his collar.

He found himself mesmerised; yes. Yet it was not the flesh which produced the effect. No – it was merely the face, merely the face which so reminded him of something . . .

He shook his head to clear the muddle of thoughts, and hurried back to the deck. He looked down at Nim in the dinghy, and held the child aloft. “Take it,” he said.

“What – what is it, Master?”

“It is a child,” Ephram replied. “But do not eat it.”

Nim got to his feet, and stretched out his arms for the infant. He looked down at it with hungry eyes; and then turned helplessly to Ephram.

“I warned you once,” said Ephram, as he disappeared once more below deck.

He returned to the hold, where before he had seen a number of trunks scattered about. He opened each of them, and rummaged through them, till finally he discovered what he sought. Here was a whole stack of travelling papers, complete with what information would have been required to compile a census of every individual who had been aboard the ship. But he saw only two documents which could have belonged to children so small as the one he had found – and one of the names was male. The infant from the cabin, he knew, was a little girl. And how did he know? Well, he simply did.

He looked carefully at the paper he held.

Anna von Wessen,

it read,

of Germany. Ten months old.

He folded the paper, and tucked it into his pocket. Then he went back to the dinghy, and situated himself once more upon the wooden bench. He took the child from Nim, and looked down again into its face.

“What are you going to do with it, Master?” asked Nim.

“I am going to keep it,” rejoined Ephram. He frowned, and added, “You see it’s not much good for eating, anyway, with its blanket all full of its own filth. And look how small and boney! Hardly a mouthful, really.”

Nim looked at him as if he had gone mad. “What was that, Master? What was that you said first?”

“I am going to keep it.”

“As a – as a pet?”

“No. First I will change it – and then I will raise it.”

“Raise it, Master?”

“Yes.” Ephram looked long into the child’s dark eyes, and twirled its soft black hair round his finger. “As my own.”

Nim said nothing more outright; but muttered something very softly, which Ephram was too preoccupied to notice.

~

Anna von Wessen, hardly a year old when discovered on board a deserted ship in June of 1936, underwent immediately the process of transforming into a Lumarian. King Ephram sank his teeth into her infant flesh, and mixed with her blood the poison of the Lumaria. She grew, still, just as she would have done otherwise; but after a time it stopped, like a flow of water through a frigid cavern. Come the present day, her face had not changed in the least for more than fifty years – but she had long grown used to that.

Everyone wondered, of course, why Ephram had done what he did. Why rescue a human child, the tenderest and tastiest of all morsels – and make it immortal? But the answer to this question was quick to reveal itself. The very first time Ephram looked upon Anna von Wessen, with her dark hair and eyes, he saw Vaya Eleria – come back to him from the grave.