April Queen (24 page)

Authors: Douglas Boyd

Returning to France in high spirits, he summoned Eleanor and his infant son to Rouen, where they moved into the palace built by his grandfather. Biding his time, Henry now made peace with Louis. In consideration of 1,000 silver marks as a ‘fine’ or gift, Louis ceased to include ‘duke of Aquitaine’ among his titles, which he had been doing since the divorce on the strength of the argument that Duke William X had given his patrimony to Fat Louis when asking him to arrange his daughters’ marriages and that Eleanor had become duchess by virtue of her marriage to him as Fat Louis’ successor. In Bordeaux during September 1154, Geoffroi de Lauroux sniffed the wind again and proclaimed that the master of Aquitaine was henceforth Henry of Anjou.

17

Under the obligations of homage for his domains, the duke of Aquitaine had to perform military service for his king when called upon. After recovering from some unspecified but severe illness, Henry rode at the head of a large body of men to help Louis pacify the ever-restless Vexin. It was during this time that messengers from Archbishop Theobald arrived a few days after Stephen’s death on 25 October to announce that the duke and duchess of Aquitaine and Normandy could now add ‘king and queen of England’ to all their other titles.

Stunned at Eleanor’s rapid rise in the world, Louis left Paris on pilgrimage to Compostela. He did not ask her and Henry for the safe conduct to which he was doubly entitled, both as a pilgrim and as their liege as far as their continental possessions were concerned, but travelled by a roundabout route, via Montpellier and Catalonia,

18

which had the advantage of giving him the opportunity to con the Christian courts of Spain for a new wife.

Neither Eleanor nor Henry could have cared less what he was up to at the moment. In a fever of impatience to claim the crown of England, Henry assembled within less than a fortnight a fitting host that included Eleanor’s now widowed sister Aelith, his younger brothers Geoffrey and William, and the chief barons and prelates of Normandy. Diplomatically, in order not to alienate the many enemies she had made across the Channel, the Empress Matilda was not included in the party, but left to keep the peace in Normandy.

By now Bernat de Ventadorn was accepting of his fate, for did not

fin amar

require the lover to submit to his mistress’ will, however much it hurt?

Domna, vostre sui e serai

del vostre servizi garnitz

Vostr’om sui juratz e plevitz

e vos etz lo meus jois primers

e si seretz vos lo derrers

tan com la vida m’er durans.

[Sworn to your service / I am and ever shall be, lady. / You have no truer man than me / for of all joys you are the best. / My love will never fail the test / as long as life is in me.]

Two years later, comforting himself with the knowledge that she still heard his songs, albeit sung by other voices, he was still proposing himself in verse as her valet and devoted bedroom slave, asking in return no greater favour than the privilege of drawing off her boots when she undressed.

19

With no intention of letting the twenty-year anarchy of Stephen’s reign continue a day longer than necessary, Henry intended arriving in England in a manner that would show the Anglo-Norman magnates from the outset the way they were to behave in future. Thus, with only a small retinue of personal servants, Eleanor found herself on arrival at Barfleur seven months pregnant, surrounded by eminent nobles and churchmen who had been on the Second Crusade and witnessed at

first hand her disgrace after the massacre on Mount Cadmos and her humiliation after the abduction from Antioch. This was her moment of triumph, looking each of them in the face, and requiring the proper deference due to the mother of their overlord’s son, about to produce another child by him – and not a mere consort like any other but a queen/duchess/countess whose own possessions far outweighed theirs.

For a whole month, this uneasy court-in-transition marked time in the little Norman seaport near Cherbourg. As though to remind Henry that his might was only temporal, November gales blew in from the Atlantic day and night, making it impossible to put to sea. His frustration can be imagined. They were still stormbound on 7 December when, determined to celebrate Christmas wearing the crown of England, he ignored the lesson of the

White Ship

sinking in that very place and embarked himself, Eleanor and the infant Prince William in a virtually identical clinker-built vessel with high bow and stern, and rigged with a lateen sail that enabled them to cross against the westerly swell, rolling and tossing on a grey sea under a leaden sky. It was for Eleanor a replay of her storm-tossed voyage across the Mediterranean on returning from crusade.

The weather was still so bad that even with sails reefed the convoy was scattered before nightfall, after which the usual station-keeping devices of horn lanterns and bugle calls were useless. For more than twenty-four hours, humans and horses were buffeted by wind and tide until the individual vessels made land in harbours widely separated. Henry and Eleanor first set foot on the land of their new kingdom in the New Forest near Lyndhurst, where William Rufus, after a reign of four years, had been assassinated under cover of a hunting accident, permitting Henry’s grandfather to seize the crown a few days later.

Their first call was at Winchester to secure the royal treasury, commandeering fresh horses on the way and gradually acquiring a cortège of Anglo-Norman prelates and nobles, drawn to Henry’s banner by the news of his apparently miraculous arrival, borne on the wings of the storm. From Winchester they progressed to London without a hand lifted or a sword drawn in protest, thanks to Archbishop Thibault of Canterbury, who had assembled the bishops of the realm to acclaim their new monarch.

The abbey at Westminster

20

upriver from London was the traditional place for coronations, but had been vandalised by Stephen’s mercenaries during the civil war. The adjoining palace, built by William Rufus for his scandalous court on the site of an earlier Saxon palace, was uninhabitable for the same reason. So Henry and

Eleanor set up court south of the River Thames in Bermondsey. On the Sunday before Christmas, they were crowned king and queen in a curious mixture of pomp and squalor in Westminster Abbey, walking out of it to the English cheers of the Anglo-Saxon lower orders and the Norman-French and Latin acclamations of the nobility and clergy.

The Jersey poet Robert Wace, who shortly afterwards wrote

The Story of Britain

,

21

based on Henry of Monmouth’s fanciful history of the kings of Britain and dedicated to Eleanor, most probably based his depiction of the legendary King Arthur’s coronation feast on hers and Henry’s. There was no shortage of food for the upper stratum of Anglo-Norman society. While mutton was not much in favour, beef, pork and game were consumed in large quantities. Game could be fresh all the year round, but beef and pork had to be salted for winter consumption when the animals not required for breeding were slaughtered in what the Norsemen had called ‘blood month’, or November. As a result, dried herbs, pepper and other imported spices were used heavily in stuffings, sauces and marinades to disguise the saltiness and cover the unpalatable taste of rotten meat.

Most bread was wheaten or rye, the cause of the disease called St Anthony’s Fire when made with ergot-infected flour, causing convulsions, miscarriages, dry gangrene and death. Omelettes, stews and pies were common, and fish was consumed in quantity, with palaces and monasteries having their own fish farms to guarantee a supply for Fridays, Lent and the many other meatless days. To cleanse the palate there was a wide range of sweet desserts – fruits fresh, stewed and candied, jellies, tarts, waffles and wafers. While the natives preferred to drown their sorrows in ale and beer, their masters preferred wine.

The waferers, whose speciality was making and serving the thin pastries eaten at the end of the meal with sweet white dessert wine, were also the cabaret.

22

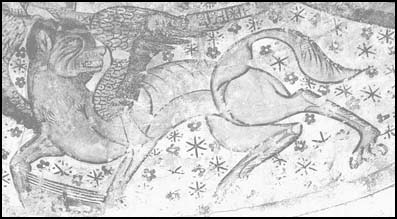

Henry’s personal waferer, Godfrey, was rewarded for his services with the manor of Liston Overhall in Essex, which remained in his family for several generations. There were tumblers of both sexes, storytellers, conjurers and jugglers, farters, singers and musicians playing bowed and plucked stringed instruments, harps, lyres, flutes of various kinds, shawms, bagpipes and other instruments. Chrétien de Troyes describes a wedding at which girls sang and danced. There were chess and backgammon boards for those who wished to gamble fashionably, and dice for those whose taste was less refined.

While many court entertainers were rewarded only with clothes and food, Roger de Mowbray, earl of Warwick at the time of the coronation, was more generous, bestowing land on several of his

favourite entertainers. One who was both viol-player and

joculator

was rewarded with a life-interest in a small estate in Yorkshire for the annual rent of one pound of pepper. Henry’s jester Herbert was given thirty acres in Suffolk. Roger the Fool doubled as keeper of Henry’s otter-hounds in 1179, for which he was given a house in Aylesbury.

23

They and other jesters, whose predecessors’ function had been retelling the

res gesta

or great deeds of past heroes, were now jokers whose irreverence was indulged so long as their wit was faster than that of their masters. There were also some female comedians, known as

joculatrices

.

The coronation festivities over, Eleanor at the age of thirty-two was the consort of the man who ruled from the Scottish border to the frontier of Spain. Mother of his son and heir, and conscious how great a part her wealth and possessions had played in his rise to this position of power, she had every reason to feel secure in her marriage to Henry.

Court Life with Henry

N

ine decades after William the Conqueror imposed his Norman followers on the population by dispossessing the native nobility, England was still an occupied country ruled by an elite of 200 Anglo-Norman families, all related in easily traceable degree.

Although they complained that it was impossible to tell any longer who belonged to which race because of the intermarriages that had taken place with girls of native stock, the gap between the French-speaking equestrian classes and their Anglo-Saxon under-lings was painfully obvious from the viewpoint of the conquered.

1

The replacement of the slavery prevalent under the Saxon kings by serfdom was a legal improvement in the lot of the most wretched, but in practice the only significant difference was that a slave could be sold separately, while serfs were tied for life to the land on which they were born and could only be sold with it.

French continued to be the language of the law courts and of the royal court for another two centuries, although legislation was

couched in Latin for greater precision. Among the upper classes, those who spoke ‘proper’ French despised others with an English accent and usage. Clemence, a nun at the aristocratic convent of Barking who wrote a life of St Catharine shortly after Eleanor’s arrival in England, apologised to her patrons – probably the new king and queen – for using ‘a poor English kind of French’.

2

The higher one’s class, the less likely it was to have an English name, or if christened with one, to use it. Even the religious conformed to this snobbery, like the ten-year-old oblate to the monastery of St Evroul in Normandy, who lost his embarrassing English baptismal name to become Ordericus Vitalis. Ecclesiastical re-baptism like this could pose theological problems: Augustine, who had been ‘Henry’, worried that prayers for the salvation of his soul could go astray if incorrectly addressed.

So fashionable were the names of the Conqueror and his barons

3

that a William, Richard, Robert, Roger or Hugh needed to add a nickname, toponym or the patronymic

fitz

to distinguish himself from all the others. At the highest level of society even Henry I’s native first consort, whom he married to bridge the gap between what remained of the old ruling class and their Norman conquerors, had been obliged to change her name from Edith to Matilda to avoid open mockery at court.