April Queen (26 page)

Authors: Douglas Boyd

There were billeting officers, messengers coming and going, cooks, grooms, dog-handlers, washerwomen, chambermaids and the whores to which Walter Map took exception. In addition to all these humans there were dogs, falcons, the baggage train of pack animals and wagons carrying bedding and chapel furnishings, the ridden palfries and led remounts and destriers of the knights.

Within this mobile

familia

or household, each royal servant had his jealously guarded area of authority and responsibility, with his own servants. The household administrative machinery ensured that everyone received the right daily allowances of money, food, drink and candles. The chancellor was given five shillings a day, plus three loaves, four gallons of fine wine and four of table wine, a large candle and forty candle ends. Further down the ladder, a chamber-lain got two shillings and one loaf, plus four gallons of table wine, one small candle and twenty-four candle ends. On the bottom rung, the lowliest attendants received only their food and some clothing from time to time. Some offices became hereditary, as with William the Marshal, whose father and grandfather and brother also served as marshals to their kings.

It has been calculated

18

that King John’s court moved thirteen or fourteen times in an average month, making it rare to sleep in the same place more than two or three nights in a row. Henry, who cared little for physical comfort, was even more restlessly mobile, and it must have come as a relief to Eleanor and her ladies when he decided to enjoy his favourite sport at one of the royal hunting lodges or the court tarried in one of the palaces at Westminster, Winchester, Windsor, Northampton or Woodstock. There, in addition to the legendary maze, was a zoo of lions, leopards, lynxes, camels and other exotic presents from foreign rulers.

For Eleanor, court life was devoid of privacy, whether at one of the royal palaces or on the road. The very desire for solitude was considered aberrant in lay people and a sign of piety in anchorites.

Until recently all the court had slept in one great hall. Twelfth-century manor houses where Eleanor stayed on her travels were, like Oakham Hall in Rutland, one huge undivided space with a solar at one end where she and Henry could sleep when his interest did not take him elsewhere. Even there, they were never alone, and anyone entering or leaving could plainly be seen by everyone in the main hall.

Under normal circumstances the distance the court travelled in a day was limited by the sumpter train to twelve or fifteen miles over roads that had not been paved since the Romans left Britain and were often no more than potholed tracks. The main roads were collectively the king’s highway, with those lords through whose territory it ran responsible for its upkeep; they were wide enough for two wagons to pass or a dozen horsemen to ride abreast.

The provisioning in fodder and perishable foodstuffs like milk and meat was a considerable forward-planning operation. The royal

bouteiller

or butler had 700 tuns containing 20,000 gallons of varied wine to move around the country to where it was needed. Henry’s bakers numbered four, but were split into two teams, so that two men and their helpers were always one stage ahead to ensure the provision of sufficient wood and heat the ovens long before the court arrived, by when it was already too late to begin baking. Whenever the king changed destination en route, there was no fresh bread that night.

Henry’s erratic progresses were in complete contrast to those of his grandfather Henry I, who always stuck to published itineraries so that petitioners and merchants and vassals knew where to find him and the business of the realm could be conducted in a calm and measured manner. The land through which Eleanor and her husband travelled had suffered greatly during the civil war. Although the weather was mild during the medieval warm period, and the upper limit of cultivation extending to the 1,000-foot contour, many manors that had been assessed in Domesday as fertile and productive farmland were producing no revenue and therefore no tax. Pastureland had gone to scrub, the livestock driven off by one side or the other, the herders also driven away or dead.

In towns, trade was poor. The forests were infested by dispossessed peasants with a price on their heads if for no other reason than their defiance of the forest laws that made a crime of collecting dead wood for a winter fire, let alone killing for food a deer reserved for the sport of their Norman oppressors. While Eleanor’s legendary contemporary

Robin Hood may never have existed, the fourteenth-century ballads casting him as a Saxon hero resisting Norman oppression give a fair picture of life in occupied England a century after the Conquest.

The court being often far from London, Becket’s house there became the place for the fashionable and ambitious to be seen. Although drunkenness and lechery were discouraged by its puritanical master, his generous table and well-stocked cellar attracted a constant stream of visitors, who complained about the comparatively sparse fare Henry considered adequate for himself and his guests – half-baked bread, sour wine, stale fish and meat.

19

As his influence grew, Becket’s household became swollen with sons of the nobility, sent to learn the ways of the world in the expectation that they would return as belted knights.

20

Newly arrived emissaries from Paris and Rome called first on England’s powerful chancellor, not for the good cheer to be had at his table but to learn the king’s mind from the man who knew it as well as he did himself.

Becket had a staff of fifty or more clerks and accountants working all hours under him, and his house so rapidly became the political centre of England that Henry complained of feeling deserted. Yet such was Becket’s usefulness that he continued to receive presents and privileges from his master, one of which was a political time-bomb in the form of an exemption from the requirement to keep full accounts for revenues from estates held in trust by the Crown.

In September, Eleanor moved her main home yet again – this time to Winchester, the old Saxon capital, in order to be nearer Henry, who was spending several weeks hunting in the New Forest with Becket. His nights were not spent in idleness but planning the next stage in his strategy. At the end of September, a Michaelmas council of the barons was summoned to discuss his plans to invade Ireland, a venture blessed by Pope Adrian IV – otherwise Nicholas, the only Englishman ever to occupy the papal throne.

Henry’s purpose was to impose the supremacy of papal rule on the westernmost province of Europe, which had been so important for the early Church. What he hoped to gain, apart from Adrian’s gratitude, by invading territory that represented no menace to England and would contribute little to the Exchequer, is hard to say. He was at the time only twenty-two years old – an age at which a mother like his sometimes still knows best. Empress Matilda arrived in England to discourage the Irish expedition with news that could not be ignored: her second son Geoffrey was preparing to take by force his legacy of Anjou, Maine and Touraine.

Henry’s territory, so extensive north to south that a month was required to travel from one end to the other, was perilously slender east to west at precisely that point. The journey from Tours to the border of Brittany was no more than a day’s ride. Geoffrey’s triangle of land, with its three great castles of Chinon, Loudun and Mirebeau, was therefore a wedge that might easily be used to split the fragile new empire in two. Matilda won her point: the Irish project was shelved.

By the time of the Christmas court at Winchester, Eleanor was pregnant again. On 10 January 1156 Henry left England in the care of Becket and the justiciars, with Eleanor and his children under the protection of Archbishop Theobald and John of Salisbury. Crossing from Dover to Wissant for a meeting with Louis, he belatedly paid homage for his French possessions. Continuing to Rouen, he listened to the arguments of his brother Geoffrey that the oath Henry had sworn after Geoffrey the Fair’s death should be honoured.

Henry’s reply was to attack Geoffrey’s trio of castles just after Palm Sunday on 8 April. He took Chinon and Mirebeau without difficulty, leaving his brother in possession of Loudun alone. As compensation for the others, he promised Geoffrey a generous pension of 1,000 English pounds and 2,000 pounds Angevin annually, not all of which was ever paid.

21

That situation temporarily resolved, Henry turned his attention to the Vexin around Bayeux, which had been bartered by his father to Louis in the year of Eleanor’s divorce. Another area of concern was Berry, on the eastern border of Poitou, which belonged to those enemies in the house of Blois who might well have been the ones to tap the wedge that could have split his domains in two.

Direct action in either case meant pitting himself against his feudal overlord, something for which Henry was not ready. The next months were therefore spent strengthening Rouen, the Norman treasure castle at Caen and the Angevin treasure castle at Chinon. The important Loire crossing at Tours was re-fortified and border castles everywhere overhauled and garrisoned with men loyal to him. Since loyal often meant ‘mercenary’, this generated a new round of taxes to pay his soldiery.

Like the whirlwind, Henry was always on the move, promising rewards to the obedient that had them redoubling their efforts, and handing out penalties to the disobedient. Regarding the Church on his domains as being as much his as the land its buildings stood on, wherever a see became vacant he sought to appoint a docile prelate of his own choosing.

In England, although Eleanor held no writ of regency as such, she travelled widely and in comfort, signing numerous charters that show she was far from being a stay-at-home wife and mother. The Pipe Rolls show her receiving allowances for herself and her sons, also for Aelith and her two illegitimate half-brothers, William and Joscelin. At Winchester, she introduced innovations like fireplaces and had glazed windows installed. At Clarendon, she had a kiln built by tilers especially brought from Aquitaine for the firing and glazing of elaborately designed multicoloured tiles for her apartments.

22

The intricately patterned floors show the same Moorish influence to be found at twelfth-century abbeys in Aquitaine, and hint at her pleasure in fine living, as do the mentions in the Pipe Rolls from time to time of silk hangings, carpets, cushions and other comforts. Many of these were transported on her travels, to convert her temporary accommodation into fit places for a queen to spend the night.

Now was she content just to plan the décor of castles and palaces. Queens and noblewomen operated networks of influence through arranged marriages. By betrothing one of her wards to a knight of Henry’s household, Eleanor gained ears and a voice in his council. By granting land to knights married to her women, she had their children raised with hers to ensure a continuity of loyalty. And her influence in the marriages arranged for her own daughters was of even greater importance. Once implanted in a foreign court, they could serve as diplomatic channels between country of birth and the new homeland, as Eleanor’s namesake daughter the queen of Castile did for her husband Alfonso VIII and her brother King John.

23

And her daughter Blanca or Blanche conveyed messages between him and her father-in-law Philip Augustus.

24

In June 1156 the queen was back at Winchester for the birth of a daughter, baptised Matilda in honour of the empress by Archbishop Theobald at Holy Trinity in Aldgate. Shortly afterwards, the young Prince William died and was buried beside his great-grandfather in Reading.

25

As soon as she was fit to travel again, Eleanor crossed the Channel with both surviving children to catch up with Henry in Poitiers, where Geoffroi de Lauroux was waiting to petition her for the confirmation of the liberties of the churches of Sablonceaux and Fontaine-le-Comte, granted by William X and confirmed by Fat Louis but severely infringed by Henry’s administrators of late. That the archbishop waited for his duchess’ arrival implies a certain wariness about approaching Henry with his request.

It was one of many Eleanor granted. The official history of the abbey of La Sauve Majeure noted among the glittering retinue of barons and

bishops in attendance on her and Henry the presence of ‘Thomas of Canterbury’, as Becket was later called.

26

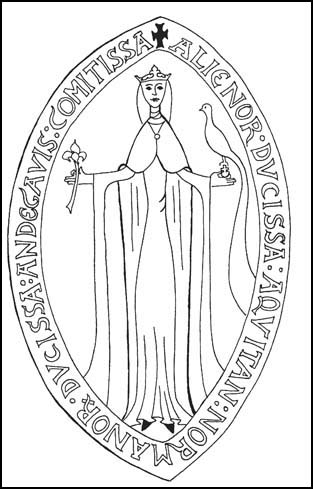

Eleanor’s seal, attached to the original deed confirming the abbey’s privileges, showed her crowned and with a sceptre in her right hand. In her left, she held an orb with the peacock of Aquitaine perched on the cross, the legend reading ‘Eleanor by the grace of God, Queen of the English’.

27

On the reverse, she held in the right hand a lily symbolising the Virgin and another orb and peacock in the other hand, while the legend confirmed her as ‘duchess of Aquitaine, duchess of Normandy, countess of Poitou’.

28

Seal of Eleanor reconstructed from fragments in the Archives Nationales de France and elsewhere

The insult to Henry four years earlier in Limoges still rankled. Shortly before Martinmas on 11 November, he returned there to raze the castle walls, recently strengthened to keep the dissident townsfolk at bay. As guarantee of future good behaviour he took hostage the young Viscount Aymar and entrusted the government of the Limousin to two Norman vassals, who did indeed keep the peace for three years. He also punished Geoffrey of Thouars for siding against him in the dispute with his brother two years previously. So swift was the fall of Thouars that rumours began to circulate of treachery, when the real reason was his lifelong rule of moving fast and striking before the enemy saw him coming. To make the point that Henry’s authority as duke of Aquitaine came from the marriage to her, Eleanor was present as the walls of Thouars Castle were torn down,

29

its seigneur banished and replaced by a trusted castellan.

30

It seems to have been her idea to force the captives taken in this adventure to make donations to her favourite religious foundations, as an alternative to being held to ransom.