Ardor (32 page)

Authors: Roberto Calasso

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

There is life when something is still also something else. There is death when something is only itself, a rigid tautology. This was one of the implications of the doctrine transmitted to

Ś

vetaketu and his father, Udd

ā

laka, by the king of the Pañc

ā

las. That day, a warrior instructed a brahmin master and his son. The king didn’t refrain from pointing out how unusual the event was. Not only was Udd

ā

laka unfamiliar with the doctrine, but—said the king—“this knowledge, before you, had never reached the brahmins.”

And yet Udd

ā

laka had taught his son the doctrine that goes

beyond.

But the path of the esoteric is endless. Now it was for Udd

ā

laka to present himself as a disciple, a

brahmac

ā

rin

just like his son. Each time, it was a question of starting over again. And it was he himself who suggested this. “We shall go back down and present ourselves as disciples.”

There are two versions of what happened that day, one in the

Ch

ā

ndogya Upani

ṣ

ad

, the other in the

B

ṛ

had

ā

ra

ṇ

yaka Upani

ṣ

ad.

They match each other, but with small, telling variations. The five questions put to

Ś

vetaketu, not by a king but by one of his own followers, and which

Ś

vetaketu was unable to answer, mostly related to the two ways that open up after death: the “way of the gods,”

devay

ā

na

, and the “way of the ancestors,”

pit

ṛ

y

āṇ

a.

But they also included a strange, apparently unrelated, question: “Do you know how, at the fifth oblation, the waters take on a human voice?”

In order to explain what ways there are for leaving the world and how they are reached, the king of the Pañc

ā

las had first to explain how the world is made, starting with the celestial world. “That world,” he said, was made of fire. But rain, earth, man, and woman are made of the same element, which is also a god: Agni. All are made of fire.

He then had to describe what fire is made of: logs, smoke, flame, embers, sparks. To explain

how

the celestial world, rain, earth, man, and woman were fire, he had to show in what way they were connected to each of their parts. The thought that operates by way of nexuses, correspondences,

bandhus

, is exacting, it does not allow for vagueness. And so, this time, man and woman appeared in the vision of the king of the Pañc

ā

las: “In truth, O Gautama [as Udd

ā

laka was often called], man is Agni: words are the logs, breath is the smoke, the tongue the flame, the eye the embers, the ear the sparks.” Certain words in the

B

ṛ

had

ā

ra

ṇ

yaka Upani

ṣ

ad

version vary, but the essential nexuses are confirmed: “The word is the flame, the eye the embers.”

As for the woman, her correspondence with the fire was entirely sexual: “Logs are her womb, her attraction to man the smoke, her vagina the flame, the embers coitus, the sparks pleasure.” An erotic compendium. But we should not think that the Vedic vision of women is so limited, despite it being so acute. The point was this: the equivalences with Agni, relating in order to the celestial world, rain, earth, man, woman, were at the same time a sequence of oblations to Agni—and the woman served to make it possible to pass to the

fifth

oblation, for it is in the woman’s fire that “the gods offer the seed; from that offering man is born.” And only at this point—after the

fifth

oblation—can we understand what the answer was to the mysterious question put to

Ś

vetaketu: “At the moment of what oblation do the waters take on human language, do they rise up and speak?”

Ś

vetaketu’s reply ought to have been: at the

fifth

oblation, because it is then that the waters protect the embryo for several months, until they become the voice of the human being that is born. It all fitted together. Not only the nexuses, the correspondences with fire and its constituent parts, but also—no less important—with the ritual order, therefore with the order of the oblations, which are each linked to the other like a sequence of equations.

But there was something that interrupted them: death. Man is conceived, then “lives so long as he lives. When he dies, he is placed on the fire. His fire is Agni, the logs the logs, the smoke the smoke, the flame the flame, the embers the embers, the sparks the sparks.” Until a moment earlier, it seemed that the embers and the sparks might be transformed into anything whatsoever—and that everything was ready to be transformed into them. But now, all of a sudden, they were just embers and sparks, simple repetitions of themselves. Now, at the moment of cremation, it turned out that the logs were the logs, the flame was the flame—and, even if out of discretion it wasn’t spelled out, the corpse was the corpse. It is difficult to imagine an

inference of death

that could be harsher, more unclouded, more clear-cut than these few tautological words.

* * *

“Thereupon he goes off, on foot or by cart; and, when he has reached what he considers to be the boundary, he breaks silence. And when he returns from his journey he maintains silence from the moment when he sees what he considers to be the boundary. And, even if there were a king in his house, he would not go to him [before having paid homage to the fires].” Behind the terse prose of the ritualist, we glimpse all the pathos of the journey: of any journey, as though Nerval or Proust were to recognize their own bedrock here. One has truly departed, and therefore can leave the silence that distinguishes the delicate phase of transition, only when the fires—or, according to another commentator, the roof of one of the fire huts—can no longer be seen. And the same when returning. Homeland, home—these are the fires. Even if a king were in your house, you have to pay homage first of all to the fires. There is something so intimate, so direct, so secret in each person’s relationship with his fires that it seems to suggest a model for every personal relationship.

XI

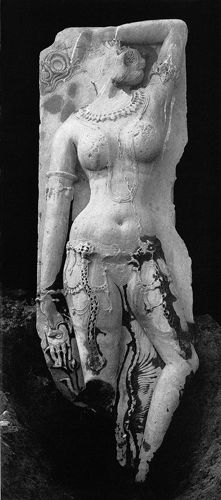

VEDIC EROTICA

The altar is a woman with perfect proportions: “With broad hips, shoulders a little less broad, and narrow at the waist.” Like a woman, it must not be naked. It is sprinkled with fine gravel or sand, so as to cover its body with a light gleaming film (“gravel is certainly an adornment, since gravel is fairly luminous”). Then with twigs and grass. The woman—the altar—makes herself beautiful, is helped to look beautiful, ready for the arrival of the gods. And so she passes a night.

At last she meets her lover, fire, “for the altar (

vedi

) is female and the fire (

agni

) is male. And the woman lies there embracing the man. And so a fruitful intercourse takes place. This is why he raises the two extremes of the altar on two sides of the fire.” Every sacrificial act is interwoven with a sexual act. And vice versa. This is the nature of how things are. Arranged to attract the gods, so that the gods are aware of the sacrifice. How is it done? How can the altar be made “pleasing to the gods”? By ensuring as far as possible that it resembles a beautiful woman. The altar, then, cannot be just a roughly hewn stone. Instead “it should be broader on the west side, narrower in the middle, and broad again on the east side.” Thus, looking at it, the gods cannot fail to feel attracted, as if by a beautiful woman lying motionless in a clearing. Awaiting her lover, her officiant, her victim.

* * *

The sacrificial setting was also an erotic one. One in which the intercourse didn’t have to take place under the eyes of many, as in the horse sacrifice. Sometimes the appearance of a female was enough for the seed to be spilled. This was how some of the most powerful

ṛṣ

is

were born, owing to the superabundance of their mental life. They were born, in fact, without their father needing to touch the body of their mother. So pervasive was his desire,

k

ā

ma

, that Praj

ā

pati—K

ā

ma was another of his names—spilled his seed at the mere sight of V

ā

c during a long sacrifice. It was a three-year

sattra

that he was celebrating together with the Devas and even with the S

ā

dhyas, the mysterious gods who had preceded the Devas: “There, at the initiation ceremony, V

ā

c arrived in bodily form. Upon seeing her, the seed of Ka and of Varu

ṇ

a spilled simultaneously. V

ā

yu, Wind, scattered it into the fire as he pleased. Then from the flames was born Bh

ṛ

gu, and the seer A

ṅ

giras from the embers. V

ā

c, upon seeing her two sons, while she herself was seen, said to Praj

ā

pati: ‘May a third seer, in addition to these two, be born as my son.’ Praj

ā

pati, to whom these words were spoken, said ‘let it be so’ to V

ā

c. Then the seer Atri was born, equal in splendor to Sun and Fire.”

This occasion was not unusual among the many events we come across in the life of Praj

ā

pati. On the contrary, it was a pattern that was set to recur, over and over again. Such episodes appeared frequently in the stories of the Devas and the

ṛṣ

is.

If it is not Praj

ā

pati spilling his seed, it is his four sons—Agni, V

ā

yu,

Ā

ditya, Candramas—who spill it watching U

ṣ

as passing before them. Mitra and Varu

ṇ

a spill it into a ritual bowl, during the

soma

rite, while they watch Urva

śī

. And there are many stories of

ṛṣ

is

who spill their seed watching an Apsara (Bharadv

ā

ja watching Gh

ṛ

t

ā

c

ī

, Gautama watching

Śā

radvat

ī

, N

ā

rada watching a group of Apsaras bathing). These scenes show one of the

ṛṣ

is

in solitary meditation, who is disturbed by the sudden appearance of a female being, generally an Apsara. But, for the gods, everything happens during a sacrifice, as if the erotic charge were always there and ready to be released at every liturgical scene. And the theory envisaged it. On various occasions, to justify the silence that has to accompany particular parts of the ritual, the

Ś

atapatha Br

ā

hma

ṇ

a

says: “For here in the sacrifice there is seed, and the seed is spilled in silence.” From the moment when the fires are kindled to the end of the liturgy we find ourselves inside a field of erotic tension—and actions culminate in moments of silence in which the seed is spilled.

The

ṛṣ

is

born from the sacrificial blaze have a mother, because the flames are the vagina of she who has seduced that god or those gods who have procreated them. And so V

ā

c will demand another son from Praj

ā

pati from the same flames that have produced Bh

ṛ

gu and A

ṅ

giras. Considering how persistently the theory and practice of semen retention has been developed in India, culminating in Tantrism, it is all the more astonishing how often scenes of semen emission without contact appear in the earliest texts. The

Ṛ

gveda

describes it with total clarity in relation to Mitra and Varu

ṇ

a before the appearance of Urva

śī

: “During a

soma

sacrifice, excited by the oblations, they simultaneously spilled their seed in a bowl.” This time the seed of the two gods isn’t received by the flames, but by a ritual object, the

kumbha

, a clay pot that holds the “night waters,”

vasat

ī

var

ī

.

Thus one day Vasi

ṣṭ

ha, the supreme

ṛṣ

i

, would be called Kumbhayoni, “He-who-has-had-a-pot-as-a-womb.” But the

Ṛ

gveda

also says that Vasi

ṣṭ

ha was “born from the mind of Urva

śī

.” The clay pot or the sacrificial flames were also the

mind

of the goddess or Apsara on which the gods who were watching her spilled their seed. An inseparable mixture of mind and matter. The seed of the gods spurted forth while the gods remained immobile. Urva

śī

’s mind was the vagina and the ritual bowl in which the seed was collected. Thus the hymn in the

Ṛ

gveda

addresses itself to Vasi

ṣṭ

ha: “You, the squirted drop, all the gods kept through the sacred formula,

bráhman

, in the lotus flower.”