Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (14 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

Alexander and his magic lantern.

erce human life. Hence we have the great battlefields of church, family and art, where the human players go through their moves, wrestle with their contingency, seek or suffer connection, with the result that the classical self, the individuated fortress that most of us take to be real, is going to be blown sky-high.

At first glance,

Fanny and Alexander

seems like a straightforward, realistic, slightly nostalgic evocation of life in small-town Sweden (Uppsala) at the turn of the twentieth century, a "user friendly" Bergman film markedly more accessible, say, than

Wild Strawberries

or

Persona.

Yet we see, soon enough, that Bergman's eternal conflict, his agon between life and art, logic and emotion, is still playing center stage. And the stage is indeed at the center, since Alexander's family, the Ekdals, are theater people, public servants, in some sense, whose mission it is to bring poetry, imagination, fantasy, and magic to the lives of the complacent Swedish burghers living in this town.

The film starts with the annual Christmas play, where we witness the sweetly innocuous rituals of art, enlisted to remind this stolid public of

Jesus' presence among them. This conventional performance is later followed by another installment of potent images, this time in the children's bedroom, as Alexander operates his magic lantern, casting upon the walls of the room the story of the pursued Arabella, playing out his favorite role as magician, wielder of power who offers thrills and chills to his young siblings and cousins. Again conventional, this scene is also personal (we know enough of the young Bergman's love affair with magic lanterns) and literary, evoking Proust's child-artist, Marcel, equally enthralled with the

"sorcellerie evocatoire"

("evocative magic") of projecting images on a wall. One wants to add: the scene is also social, a little exercise in crowd control, a little incursion into the reality principles of what the film calls "the big world." In the long version of the film, this sequence closes with the father's (Oscar's) fulsome narrative of a magic chair, stressing still further the dual role of objects: inert and seemingly docile on the one hand, but secretly bristling as conduits of energy, passion, and history on the other.

This concern with the social and figurative reaches of art and narrative returns in a major key in the central episode of Oscar's death. Bergman needs this turn of events to launch his inquiry into patriarchy: Oscar the sweet man of theater (albeit not Alexander's blood father) versus Edvard, the repressive but passionate man of the cloth. Two fathers for Alexander: the fireworks that flow from this will carry the entire plot. But this oedipal story is brilliantly overdetermined by the stunning mediation of Shakespeare's

Hamlet.

Oscar suffers his (to be) fatal stroke on-stage during a rehearsal

of Hamlet

in which he plays the role of the ghost, the dead father. At his deathbed, Oscar tells Emilie that he will continue to be present, even in death, for her and her children. In short, he will become the ghost he played. And he does, making his entry (albeit visible only to Alexander and the spectators) into numerous scenes of familial morass: attending the wedding of Emilie and Edvard, visiting his mother to express his (justifiable) worries about the children, coming to Alexander in the attic after the bishop has cruelly whipped the boy for lying and defamation. The recurring presence of Oscar, Ham-

let's ghost, onstage merely rachets up the ontological claims suggested by the magic lantern and the magic chair: the world moves in flow and flux; the apparently docile edges of things, people, and events—this is only a chair, that is an image, Oscar is dead—are only apparent, and at crucial moments things can alter, metamorphose, and disclose a new kind of traffic.

One reason that

Fanny and Alexander

is among Bergman's most lovable films is that the metaphysics of flow and flux is not presented as some form of occult theology or head game, but rather as the actual living pulse that moves our everyday world. It only

looks

still and docile. Bergman's camera gives us lingering close-ups of the masks, puppets, costumes, and other paraphernalia of Isak the Jew's lodgings—strategically counterpointed against the barrenness of the bishop's quarters—because these objects, these artifacts are the still living, soon to be activated, receptacles of spirit and power. And the human body ranks high among these energized things; it too is revered for its indwelling powers, expressed quite wonderfully in the scene where Carl (the failed Ekdal uncle), after ingesting the gargantuan Swedish

Julbord,

treats the children to some intestinal fireworks; the third of his ritual farts, religiously attended to by Alexander, match in hand, explodes the screen into darkness, and we are led to say that apocalypse comes in many guises, and a sufficient fart may be one of them (at least

in petto).

Such carnal power is, of course, predominantly on show in erotic matters, and the now elderly Bergman treats fornication in this late film with a humor and warmth that are new and welcome, as seen in the bed that collapses under the strenuous activities of Gustav Adolf and Maj, or even in the sexual passion that brings Edvard and Emilie into their ill-fated union. Nowhere is Bergman's vision clearer than in the scene where Edvard sternly admonishes Alexander never to lie again, and then unctuously unites his new family in a moment of prayer; but when Edvard intones the pious words, Alexander hisses under his breath the

obscene anthem of the body: "Piss-pot, fuck-pot, shit-pot, sick-pot, cock-pot, cunt-pot, arse-pot, fart-pot. . ." (94). It is a fine moment, because it stages the film's warfare—not body versus spirit, but body

as

spirit—with great pith. Edvard's major campaign against Alexander is cued to the dichotomy between truth and lie, since this is the demarcation that shores up his own worldview (and explains his suspicion of art and storytelling), but the film helps us to see that lies and fictions have an ontology of their own. Hence, when Alexander

lies

about Edvard's alleged murder of his first wife and children—the lie for which he is severely beaten—the entire film trumpets out the truth of the boy's fiction: Edvard is indeed, in front of our eyes, imprisoning his wife and children and is en route (at least emotionally) to murdering them; but their names are Emilie, Fanny, and Alexander.

In this light, the replay of

Hamlet

—with Alexander in the title role, Oscar as the ghost, Emilie as Gertrude, and Edvard as Claudius—is not predominantly a saga of revenge, but first and foremost an illustration of the film's Weltanschauung or worldview: spirits live, move through the world, inhabit people and things, coerce lives. This is the truth of Bergman's film, and we see it manifested everywhere, in ghosts, mannequins, and bodies. And we hear it too, in a scream that goes through the house. That scream is worth attending to; it erupts at several critical moments in the film. One of them is when Isak the Jew goes to the bishop's quarters to retrieve the imprisoned children. This episode begins with a splendid shot of Isak serenely positioned in a horse-drawn carriage that is thundering toward us, as if to advertise the energy system that is about to go into action. Isak then waltzes through his consummately ingratiating performance with both Edvard and his sister, an exchange that is larded with Lutheran contempt, a dislike so powerful as to be visceral, as we soon enough note when Edvard later throttles Isak, accusing him of trying to steal his (!) children, the classic anti-Semitic indictment of all time. For our purposes, however, the episode's significance hinges on the magic act of rescuing the children. This is no sim-

ple matter. Isak has rushed upstairs while Edvard is counting the money (paid to him for a cupboard and a trunk), and he hurries the two children down, pops them into the trunk, just as Edvard returns to the room. The two chat amiably for a moment, then Edvard pounces on Isak, accuses him of stealing the children, and opens the trunk. And finds it empty.

Finds it empty.

The bishop then rushes upstairs, to be certain the children are still there. At this point, something happens in the film that does not appear in the film script. Isak, brutalized and shaken by Ed-vard's assault of a moment earlier, stand up, gathers himself, looks up at the ceiling, and (with a transfigured face) emits a great scream. This image of human utterance so powerful that it overcomes the laws of reality is as emblematic for my book as Munch's signature painting,

The Scream,

is. That Bergman himself saw this scene as pivotal can be documented by a photo we have of the filmmaker instructing his actor, Erland Josephson, exactly how to deliver the fateful scream. One feels that Munch's own ghost is not far away, much less Shakespeare's or Hamlet's, because this scream through the house is Bergman's great leitmotiv for announcing the reign of spirits. And they (the spirits) do their job. Edvard opens the door and sees an eyeful (as do we): Fanny and Alexander are lying on the floor, still ("perhaps dead" says the film script), with the sweaty, bedraggled, pregnant Emilie standing guard over them, forbidding Edvard to touch them, threatening murder if he does. WHAT IS THIS? We "know" the children to be in the trunk, but Edvard has looked in it and found it empty; we now "see" the children in the bedroom, where they cannot logically be. Edvard returns downstairs as the workmen carry out the trunk, which the film script now calls "heavy." The children are indeed in it, and they escape to Isak's lodgings.

How to explain this matter of invisible children? facsimile children? There is no way to avoid Bergman's logic: Isak's scream, his spiritual intervention, reshapes the material world. As we might well say, "he spirits the children out of the house." We are very close here to the

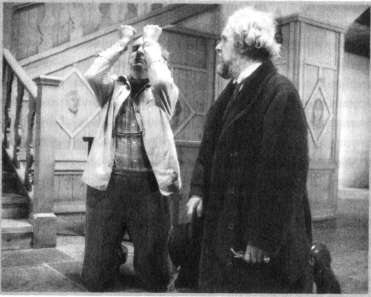

ABOVE: Isak's scream. BELOW: Bergman instructing Erland Josephson (Isak) how to make the scream.

shape-shifting power embedded in Munch's

The Scream,

a representation of the cosmic reaches of sentience, now folded into a story about saving the children. But there is more to come.

One expects the children to be safely ensconced at Isak's quarters, so that the story can wind down. But Bergman has surprises for us. Alexander, unable to sleep and needing to pee, now makes his true inventory of the Jew's strange lodgings: a wild assortment of masks, puppets, dolls, and other mannequins, including the infamous mummy that still breathes even though it has been dead for more than four thousand years. In addition to these exotic and disturbing material objects, we get a closer look at the exotic and disturbing human objects too: Isak's nephew Aron, who enjoys terrifying Alexander by staging the entry of the great puppet God, and—most intriguing of all—the strange Ishmael (the other nephew), whom we initially only hear of. Ishmael is kept carefully locked up in the heart of the labyrinth, and we

know

—with that delicious and awful sureness of logic that all good narrative carries—that Alexander's destiny is to encounter this enigmatic figure. We are approaching dead center.

It is a strange encounter; it is a textbook example of what

encounter

actually means in the logic of this film. Ishmael, played by a very hermaphroditic-looking Stina Ekblad, announcing thereby already a major slippage of boundaries, asks Alexander to write his name; but when the boy dutifully writes "Alexander Ekdal," Ishmael shows him that it reads, instead, "Ishmael Retzinsky." I can become you. "Perhaps we have no limits; perhaps we flow into each other" (199), says Ishmael. The old Jew's philosophy, as cited by his nephew Aron, is indeed Bergman's core system of belief: "Uncle Isak says we are surrounded by realities, one outside the other. He says there are swarms of ghosts, spirits, phantoms, souls, poltergeists, demons, angels and devils" (194). But only now do we see this theory actualized in all its unsettling force. Ishmael fuses ever more intimately into Alexander, caresses the pubescent boy—what viewer is not jolted, at this sight, into an awareness that this is a coming-of-age story in the oldest, phys-