Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (18 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

Hyde is produced by ingesting potent chemicals. Stevenson, pre-Freudian that he was, was certainly pointing to the dark underside of the psyche, ruled out by Victorian properties, but we are entitled to think pharmacalogically as well, to foresee already what kind of R and D might be out there, needed to free up our animal spirits. Is it such a stretch to say that Stevenson's fable gestures—however unwittingly— toward our culture of Viagra and other sexual enhancements?

Other literary performances on this topic in the nineteenth century are less overt, but still more profound. I am again thinking of Charlotte Bronte's classic novel

Jane Eyre,

in which the gende, diminutive Jane is doubled by the monstrous, intemperate, unchaste Bertha Mason Rochester, the "madwoman in the attic" whom we have learned to see as Jane's alter ego, thanks to the insights of modern feminist criticism. Much to ponder here: for more than a century, it never occurred, even to the boldest critics, that the "mad, bad and embruted" Bertha could be understood as Jane's "other." Certainly the advent of Freud matters here, in that his notion of repression signifies a kind of personal and cultural policing that we do to deny the animal side of things. And today anyone can see that the entire plot of Bronte's book depends on

locking up

the animal, a carceral project that fails, not only once (when Rochester leads the wedding party up to the infamous third floor of Thornfield where Bertha is kept caged) but over and over throughout the novel, as we hear the animal's infernal laugh, glimpse her bouts of violence, sense her roaming. The animal is nothing less than libido itself, i.e., the energy system that drives bodies, a view that Victorian thinking proscribes with all its might.

We will never know how much of all this Bronte intended—it is the first question my students ask when I suggest this libidinal interpretation of a book many of them have read in much more innocent fashion— and my only answer is: can we know what any author intends? what we ourselves intend? Novels are not subject to proof or disproof, like evidence in a courtroom, and we have everything to gain by taking liberties with Bronte, because the pieces of her story then fit together with an ir-

resistible logic.

Jane Eyre

(the novel) is

thinking

about sexuality and an-imality, about the presumable transition from animals to humans Just as the

Oedipus

and the

Philoctetes

are. In Sophocles, incest, parricide, and misanthropy result, whereas the damage Bronte (unwittingly?) charts is of a different order. Bertha's potent mix of sexuality and rage gets quite a run: the animal tries to burn the bullying patriarch alive, ends up torching the castle and blinding/maiming him in the process. I'd say that some overdue nineteenth-century bills are being paid in this text. What other kind of map could possibly show us these things? I can think of few literary examples that display more perfectly why art matters, what it is good for, what it enables us to see and hear.

Jane Eyre

speaks volumes about Victorian censorship, about the range of things between heaven and earth that its philosophy cannot comprehend, but that the artist intuits nonetheless. I say "volumes" are spoken, in that the "animalizing" of Bertha comes to us, more than 150 years later, as a double story of denial and liberation: the surface plot goes through its paces disciplining the unruly body, whereas the other plot offers a staggering critique of these moves, showing how ideologically resonant terms such as

mad, bad,

and

embruted

are, and how doomed the coercion scenario is.

In similar fashion, Biichner's

Woyzeck

tells us a great deal about a subject we encounter all too frequently today—the outbreak of domestic violence and murder; it is no accident that this play is based, at least in part, on three documented cases of men murdering their wives or mistresses in early-nineteenth-century Germany—and we are asked to ponder the connection between "beastiognomy" and social arrangements. Woyzeck, the lowest of the low, is systematically abused, and the author seems to be asking: how much does it take to push a man over the edge? The animals are everywhere: at the circus, on the street, in the beds. The critic Richard Schickel once suggested that a proper staging of the final scene in which Woyzeck is on trial for the murder of Marie should bring the animals back in, let them mosey into the courtroom and see what is being done to their kind. Buchner is very much the sci-

entist and the political scientist in this play, seeking to gauge the nature and causes of violence, locating his answers both in the libidinal/neural equipment of the human species and in the economic order of the culture. We have not solved these questions. What causes domestic violence? why does someone walk into a subway car or a post office or a McDonald's and proceed to blow everyone away? One thing is certain: bodies, under sufficient pressure, explode. Literature helps us understand such eruptions as a social story.

KALEIDOSCOPIC BODY AND VISIONARY ART

I have said that our customary perception of the body cheats us by

naturalizing

what it sees. The entire project of visionary art and literature consists in

denaturalizing,

or, as William Blake famously put it in

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell,

restoring to us a true vision of things by dint of a perceptual cleansing: "If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite./For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern" (73). Drawing doubdess on Plato's parable of the cave, according to which we see only shadows and reflections, Blake spells out one of the criteria of art: to open our doors of perception. Blake himself was a fierce social critic, looking at the power grid of late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century England with the eyes of a visionary, and much of the destabilizing virulence we saw in Biichner and Bronte has a Blakean tinge to it. In particular, Blake celebrated what we today would call

libido,

but the word he used for it was

Energy,

which he saw as "the only life" and "from the body," which he also viewed as the source of "eternal delight."

But we can learn about the body's surprises and unruliness in other ways, too, from texts that have no cultural agenda whatsoever. I am thinking of Rilke's hallucinatory prose work, written during his youthful stint in Paris in the early years of the twentieth century,

The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge,

in which the artist Malte seems almost cursed

by having his perceptual doors cleansed. One of the motifs of the

Notebooks

is the repeated refrain, "I am learning to see,"

"Ich lerne sehen,"

and that is what art does: it teaches us to see. Not in the retinal sense of accurate information gathering, but in the inner, imaginative sense of grasping an emotional or psychological truth. Rilke's Malte is a man experiencing Parisian squalor, its carnival of down-and-out city dwellers who wear their misery on their faces, but he encounters them, as it were, without defenses, as an observer whose membranes are too thin, whose insides seem to be on the outside ("Electric trolley cars speed clattering through my room. Cars drive over me"). Not that Rilke has a program, wants you to improve urban conditions; rather, he shows how precarious and violent life is, how tumbling and dizzying it all is, how risky it is to

look.

To be sure, no reader would like to change places with him. Yet, we are enlarged by his explosive, jolting perceptions, helped toward a view of experience that is more generous, even if more turbulent and capsizing, than the firm scheme (our flesh included) we take to be stationary.

One of the text's most celebrated passages focuses on the body: not the body of a Parisian derelict, but Malte's own body. He is remembering an episode from childhood when he was coloring. At a certain point, the red crayon fell under the table, and the boy, numbed from the position he'd been in, went after it. Finding himself on a fur rug, no longer entirely clear what is his and what is the chair's, the child tries to accustom his eyes to this darkness and is obliged to rely on his sense of touch to find the missing crayon. Kneeling, propped up by one hand, the other combing the rug in search of the missing object, Malte is initially disoriented, but gradually his eyes adapt to the situation, and he sees the wall, the molding, and then something else:

above all I recognized my own outspread hand moving down there all alone, like some strange crab, exploring the ground. I watched it, I remember, almost with curiosity; it seemed to know things I had

never taught it, as it groped down there so completely on its own, with movements I had never noticed in it before. I followed it as it crept forward; it interested me; I was ready for all kinds of adventures. But how could I have been prepared to see, all at once, out of the wall, another hand coming to meet it—a larger, extraordinarily thin hand, such as I had never seen before. It came groping in a similar fashion from the other side, and the two outspread hands blindly moved toward each other. My curiosity was not yet satisfied, but suddenly it was gone and there was only horror. I felt that one of the hands belonged to me and that it was about to enter into something it could never return from. With all the authority I had over it, I stopped it, held it flat, and slowly pulled it back to me, without taking my eyes off the other one, which kept on groping. I realized that it wouldn't stop, and I don't know how I got up again. (94)

What to make of this? The passage shrewdly prepares us for its discovery of one's own body as

other:

numbed body, darkened setting, groping hand. Anyone who has played the game of using fingers to cast animal shadows on a wall, anyone who has gazed a second too long at his or her hand or leg or other appendage, has sensed the estrangement in play here. An overlong look in the mirror will do the same job. In my view, the horror of the passage, the

other hand

that comes from nowhere and bids to usurp all (hand, child, world), is ultimately a repeat of what we see already in the first crablike hand making movements and knowing things it has never been "taught." Such writing brings home to us how

exotic

our bodies are, how crammed with pulsions and freewheeling our appendages are (again underscoring the mirage entailed in that pronoun "our," since these somatic performances don't seem to be carrying out "our" orders, but rather doing their own song and dance). How do we learn what may be at stake in such transactions, when the body flaunts its autonomy? Sickness—a limb or an organ threatens to quit, making you heinously aware of its power, of your dependency—is one kind of crash course. Literature can be another.

Puberty,

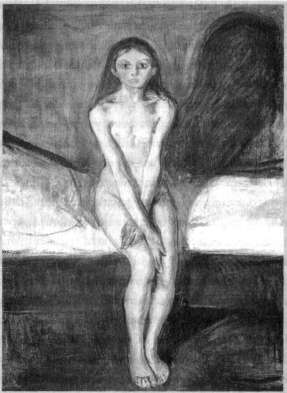

Edvard Munch, 1894.

THE BODY'S CAREER OVER TIME: PUBERTY AND AGING

Rilke's depiction of the hand/crab is a lesson in metaphor. If we tried to visualize this as a real crab, it would be a grotesque joke. But the body's

otherness

can be captured visually, and to prove this, I want to invoke a familiar painting, Munch's

Puberty,

and to investigate what is so disturbing about it. Munch's sights are invariably focused on the career of the body, and although sickness and death are his favorite topics, he shows us here that the discovery of

life

is no less unhinging. This depiction of the naked, adolescent girl, vainly and fearfully trying to shield

her burgeoning body from view, from

our

view, annihilates, for starters, any complacent notion that we might have of "spectating" as an innocent or neutral activity. Munch experiments frequently with frontal postures, but nothing quite matches the effect he achieves in

Puberty.

Merely to look at this painting is to do what this girl most fears: to ogle her body, invade her privacy. It is worth pondering the corrosive reach of these matters: how often do you factor yourself-as-viewer into the equation of art? You are a "player" in this piece, and the role you play is not nice. Looking—no less than the ontology of art, since it exists to be looked at—becomes tantamount to violation, and if you really think about viewing-as-voyeurism, you may find the next visit to the museum or the next browsing of an art book more uncomfortable and complicated than usual.

We pry when we look. And the girl knows it. The hands seek to hide the genitals but, as she seems to realize, the breasts are on view, and the expression on the face underscores the lopsidedness of the contest: naked bodies are vulnerable, cannot adequately shield themselves from harm or invading eyes. (How often do you have dreams or nightmares of being naked in public, unable to cover yourself, on show?) But we the spectators are only a part of this girl's problems. Her most unsettling discovery, the really traumatic one, is of her own body and its incredible trajectory-in-time, a trip she is just now understanding. There is a temporal treadmill on show here, an evolving curve of life that somatic creatures negotiate from birth to death, and the frightened eyes of this girl seem actually to see the woman she is starting to become, the child she is starting to leave. Puberty

itself

is no less drastic just because everyone goes through it, and in Munch's vision we recover something of its first-time shock value: the emergence of an entire physiological and sexual repertory, the actual machinery of a body that is now becoming adult-operational, shifting gears.