Asimov's Science Fiction: April/May 2013 (35 page)

Read Asimov's Science Fiction: April/May 2013 Online

Authors: Penny Publications

| 164 words

The Federal Center for Controlling Things

wishes to know where I contracted poetry,

so those infected, or at risk, can be advised.

They have a list of everything that sings,

and since my name appears on two or three

of their cross-referenced indices, I am apprised

that I have been identified as dangerous

to the well-being of my contacts, who must be disclosed

to the bureaucracy in charge of my disease.

They warn me my condition's serious,

and often leads to suicide in those disposed

to introspection and the vague unease

that poets, on the whole, spread like a pestilence

among the uninfected and naive

who think a truth innocuous because it rhymes.

Contamination is a grave offense

and I am given to believe

that, though my malady is no crime,

I still am subject to grave penalties

if I withhold the names of those from whom I got,

or those to whom I gave, this metaphoric flu,

and since I'm not the hero that I ought to be,

and though I know it's something you would never do,

I write this poem leading them to you.

| 264 words

The tent was an unfolding map

blossoming in the middle of the stadium

calculating the probabilities of our salvation

while I, hopes fractured by undecidable outcomes

leaning over the edge of the bridge above our river

thought—Why not try this path instead?

The sermon's righteous quantum fire

carried like the songs of winged bosons

bringing blessings—"You may think what happens

amid the quantum spirit doesn't affect our macro world"

the preacher in the white coat shouted,

"but all mortal things suffer wave packet decay!

In today's periodicity of so-called complex values

where we seek not to know the state

of our soul wavefunctions, but find temporary release

in visitations of spectral content

and sinful multibody interactions—"

Flash: Gabrielle and me, our last night

on the beach when things between us were still positive,

blasphemous memories of our unbroken symmetry,

superpartners who could always simultaneously

find our momentum and position...

She was a skeptical radical with hierarchy issues, an atheist

unbelieving in quantum fields,

saying strings were beautiful all on their own without a lower power.

Our final argument broke our spin

keeping our integral formulations from ever even paralleling again.

"... We are not this crude position-dependent mass!"

(the preacher insisted) "but children of the Highest Energy Band,

our sins forgiven from the problematic outcome

condemning us to an asymmetric infinite square Well

through all eternity—"

The revival didn't go over here.

We're a Newtonian town, always have been,

believing in classical results, only trusting

what we can observe with our own eyes.

I don't fit in. My box is always open with

all potentials already decided

before I can choose.

My life has been only entropy

but wishing I could believe in an infinite energy

gluing everything in the universe together—

In the name of Probability, Interference, and Entanglement,

Amen.

I need my initial state of grace.

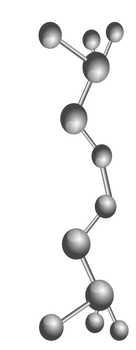

| 57 words

Breaking up

is never hard:

We had energy, once;

we collided head-on

with a center-of-mass energy of TeV,

a collision that shattered us into constituent particles

mixed together in a quark-gluon plasma.

But charm decays;

our energy radiated away

into the cosmic background.

Nothing remains but light

and the lightest of things

that cannot decay

because they have nowhere to go,

leaving only bubbles behind,

ephemeral trails

showing what we, once, had been.

| 15 words

Nice boot,

I say,

what's it made of?

Raptor's tongue flicks out, in

my wife's uncle,

he says,

very high quality.

| 50 words

When you told me

that night is us abiding in Earth's shadow,

like a daily eclipse,

I did not know enough to ask

about the time zones we create

with our own shadows.

Nor did I know enough to ask

how an absence can cast a shadow

as dark as any presence.

I'd ask you now,

but you're not here.

| 114 words

In the airport lost and found,

a janitor discovered a small vial,

tightly corked, with a label

handwritten in red ink:

to remove a curse

to reverse a course

to restore a chance

She thought of her constant debt

and deprivation. Long night hours

cleaning floors. Her headaches

etching a trough in her brain for years.

And a man she knew when the band

played Harvest Moon; the slippery

dress she wore, how he twirled her.

Turning the vial in her stiff fingers,

another label:

Take three drops on the third hour

of the third day of the third month.

(Today was March 3! Soon,

it would be 3 a.m.)

Shake well. Warning: do not use if—

Here, the script was muddled

into a red stain, like wine or beets

or blood. The barrier of if,

unknown, inevitable.

TFNG

| 948 words

2012 was a hard year for American astronauts. In last month's editorial, I wrote about Janice Voss, an astronaut who died in February and who once corresponded with us about her love of SF—most especially the works of Isaac Asimov. Her death was followed by the loss of America's first woman in space, Sally K. Ride, in July, and Neil Armstrong, the first person to set foot on the Moon, in August. While I'm saving my thoughts about Neil Armstrong for another editorial, I decided to focus this month's essay on Sally Ride and some of the other members of NASA's Astronaut Group 8.

When NASA selected thirty-five people for Space Shuttle training in 1978, it was the first new group of astronauts since the sixties. Some of these newcomers did not seem to fit the NASA's previous astronaut mold. Kathryn D. Sullivan, the first American woman to perform an EVA, said in a 2007 interview with Jennifer Ross-Nazzal, "There had never been critters that looked like us, admitted into the astronaut corps." The group looked a lot like America, though. In addition to what Dr. Sullivan refers to as "twenty-five standard white guys," Group 8's trainees included the first three African American men, the first Asian American man, and the first six American women. I'm sure my father the vet and my sister the major would be happy to know that the group also included America's first Army astronaut.

Although the news was exciting and inspiring, it couldn't have come as a surprise to those who'd read Robert Heinlein's

Space Cadet

or followed other science fiction literature and television series. In an interview for NPR's StoryCorps in 2011 about his younger brother, and second African American in space, Carl McNair said, "As youngsters, a show came on TV called

Star Trek.

Now,

Star Trek

showed the future—where there were black folk and white folk working together. I just looked at it as science

fiction,

'cause that wasn't going to happen, really, but Ronald saw it as science

possibility."

The reporters who peppered Sally Ride and the other women at news conferences with ridiculous questions did not seem to be up on their SF or completely prepared for this new breed of astronauts. (I cannot find attribution for one of my favorites, which ran something like, "What would NASA do if Dr. Ride couldn't find a comfortable position for her knees on the Space Shuttle?" Her response: "Find an astronaut whose knees fit.") Of course, the new breed was much like the old breed: brave and smart and ready to conquer new territory.

Group 8 came to call themselves TFNG, which can be politely translated as "Thirty-Five New Guys," and they were all pretty awesome. Other members of the group included Guion Stewart Bluford, Jr., a test pilot with a Ph. D. in aerospace engineering from the Air Force Institute of Technology, "Guy" was the first African American in space; Judith Resnik, the first Jewish American and second women in space, held degrees in electrical engineering from Carnegie Mellon and the University of Maryland; Frederick D. Gregory, the first African American to pilot and command a space shuttle; Margaret Rhea Seddon, a medical doctor from the University of Tennessee College of Medicine; Ellison S. Onizuka, with degrees in aerospace engineering from the University of Colorado at Boulder, he was the first Japanese American in space; Shannon Lucid, a Ph. D. in biochemistry from the University of Oklahoma who spent 188 days in space during her fifth and final spaceflight; and Anna Lee Fisher, a chemist and medical doctor, she is the last remaining TFNG still on active duty.

Fourteen of The New Guys were pilots. The rest were mission specialists. They all shared a love of adventure and a zest for space exploration that may be hard to put into words, but can be easily grasped by readers of

Asimov's.

When Lynn Sherr asked Sally Ride why she wanted to go into space, she replied, "I don't know. I've discovered about half the people would love to go into space there's no need to explain it to them. The other half can't understand and I couldn't explain it to them. If someone doesn't know why, I can't explain it." While the former test pilots must all have known about the dangers that can't be escaped when flying at the edge of the envelope, I'm sure all members of Group 8 were well aware of the inherent risks of spaceflight. In a 1998 interview with

Scholastic.com,

America's first woman astronaut said, "When you're getting ready to launch into space, you're sitting on a big explosion waiting to happen. So most astronauts getting ready to lift off are excited and very anxious and worried about that explosion—because if something goes wrong in the first seconds of launch, there's not very much you can do."

The first in-flight loss of American life occurred on January 28, 1986. Four of the seven astronauts who died aboard the

Challenger

were members of Group 8. These included the commander, Francis Richard "Dick" Scobee, as well as Ron Mc-Nair, Judy Resnik, and Ellison Onizuka. A truly American crew, which meant the disintegration of the

Challenger

brought us a whole lot of heartbreaking firsts.

Although she served on the commissions that investigated the loss of the

Challenger

and later the

Columbia, Challenger

's destruction ended Sally Ride's career in space. She became a professor of physics and director of the California Space Institute at the University of California, San Diego. Sally Ride Science and Sally Ride Science Camp for girls, organizations that she co-founded with her partner Tam O'Shaughnessy and others, continue to "educate, engage, and inspire" numerous fourth through eighth grade students.

Sally K. Ride and all TFNG contributed to a legacy that will turn children into scientists and astronauts for generations to come.