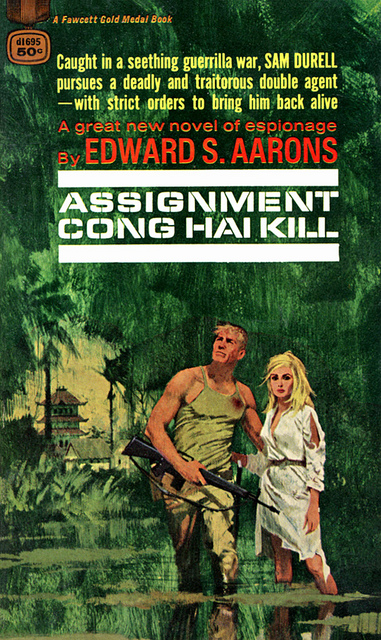

Assignment - Cong Hai Kill

Read Assignment - Cong Hai Kill Online

Authors: Edward S. Aarons

1

DROWNING, Durell felt an

inner rage because he had been careless. Just a little careless, but when you

walk the edge of a knife, every step must be calculated. He had been watching

for the girl when the mistake was made. But you only made one, in Durell’s business.

You rarely had another chance.

The water was warm and

smelled of rotting things, of vegetable scum and human excrement, of oil and

mud that gave oft foul, gaseous bubbles. He could at least have chosen some

clean water to drown in, he thought. And because the water was so foul, it gave

him a little extra determination not to open his mouth and breathe it in.

The pain in the back of

his head was not so bad. It had been a glancing blow. He wondered if the girl

had planned it, because he never saw the thug who’d come up behind him on the

plank walk across the

klong

.

His feet touched bottom.

The mud clutched like warm, licentious hands all the way up to his ankles,

pulling at him. Through his dazed pain, he felt revolted, and he wanted to

laugh, because his death was happening in such a ridiculous way, and he’d had

so many other smarter enemies who had tried to kill him. Now some half-wild

jungle villager had managed to do it. But it had happened like that to Fred

Harrison, who was pushed under the wheels of a London Underground; and Joel

Marley, hit by a taxi in Athens. Or Danny Vane, with that girl in Hong Kong.

Durell had worked with them all, at one time or another. They had been good

men, and no doubt all of them had been surprised, in that instant of dying.

He opened his eyes

underwater and saw wavering shafts of red and yellow light from the paper

lanterns of the Chinese quarter all around the canal, and it seemed as if he

had already departed this world, or was on his way, and everything was growing

dim.

Something raw and

screamingly painful cut across his cheek with a shock that almost made him open

his mouth to breathe in the water for that final lungful. His head had scraped

against a piling encrusted with thick river barnacles, and the tiny shells,

open in the night hours, presented so many serrated razors to his passing

flesh. He pushed away, a dim sense of survival returning to him. He did not

have to die. His mind was clearing. But he would have to surface fast, to drink

in air and not water. . . .

He pushed against the

muddy bottom and felt the muck release his ankles from its obscene clasp. He

drifted up toward the red, yellow, and green worms of light that lay on the

surface of the

klong

.

Too far to go.

You can’t make it.

Besides, he’s still

waiting up there.

Crouching, the other man

was a long shadow against the shadows of night, kneeling on the plank walk, the

club in his hand, waiting to smash his skull and let his brains float away in

the water like the pulp of an overripe fruit.

The shadow was

monstrous, inexorably blocking the way to precious air and life.

Wait.

But he couldn’t wait.

His lungs screamed for

air now and gave him no choice. He slid up through the murky, warm water. The

shadow of the waiting man blotted out the colored worms from the lanterns

around the places where the old Chinese men were sitting, drinking tea and

playing eternal Mah-Jongg. No one had seen the swift attack. Even if anyone had

seen it, would he have cared? There had been no alarm. Durell was alone, dying,

and his murderer knelt up there just above the surface of the water, in case he

came up again. Instinct lent him cunning, and cunning gave him a last

resentment against the death that hungered for him. His head came above the

water with a small splash.

The man waiting above

struck at once—and missed. And pulled back to strike again.

Dimly, through his pain

and fear, Durell was aware of instinctive reactions. He had another moment to

live. The reflexes drilled into him so painfully made him act almost without

volition, when part of him told himself to let it go and finish it in the warm,

viscous mud at the bottom of the canal. It was like standing aside to watch

himself challenge the thug crouching above. He could see his own bloody head

and the soggy white linen suit that hampered him. But in that instant he got a

good gulp of air into his tormented lungs. It was a small victory. But it gave

him another chance.

He let himself drift

down again, and now, slowly at first, he began to think and let his mind overcome

the shock and dismay he had felt when that first blow crashed down on the back

of his head. He remembered following the girl, Anna-Marie Danat, from the

riverfront hotel, through the hot and humid night of the coastal town that

sprawled almost within sight of the Cambodian border. They had crossed a few

paved streets, then some bridges over the

klongs

, where sampans and

barges made a solid surface over the dark, turgid water. There had been a

garden gate, oleanders, the scent of night-blooming flowers, and then the crash

and din of the Chinese quarter of the Thai town of Giap Pnom. Here

there had been a vitality of sights, sounds, and smells—dragon lanterns and

snake shops and old men sitting at their games, the noise of barking dogs and

wailing children, the odors of fish and food and opium smoke.

Where had he gone wrong?

Anna-Marie had turned

left into an alley, then along a brick-paved walk beside the canal. She headed

for a Chinese house a little larger than most. Now and then she had turned

about to see if she were being followed. But it had been easy to stay

invisible. He’d been angry with her, because her orders were to stay at the

hotel; but everything she did was suspicious, and he wanted to know where she

was going before he stopped her. If he halted her too soon, she would only lie

to him.

Better lie than die, he

thought.

In seconds, he would

have to surface again. He touched the barnacled piling again and remembered the

small bridge, the stone garden lantern beside the

klong

. Anna-Marie

had paused at a wooden gate and he was caught out in the open on the bridge.

The moon was full, like a searchlight out of the Southeast Asian sky, aimed

right at him.

Then, just when he saw

her pert French features change into alarm, he felt the pain and thrust into

the fetid Waters below the bridge. Someone had been hiding behind that big

stone Chinese lantern.

Had the girl known?

Was she smarter—or more

treacherous—than he’d expected?

No matter now. It was

time to go up again. This time, your pal waiting up there won’t miss when he

tries to bash your brains out.

His head broke the

surface of the water again.

The shadow waited, tense

and lustful for his death. The club swished down with a swift, ugly sound in

the air. Durell saw a skeletal face, a mélange of racial strains in almond

eyes, brown skin, a round shaven head. He ducked and thrust up a hand to catch the

impact of the club in his palm. His fingers closed around the shaft and he

yanked back with all his remaining strength, setting up a great splashing in

the dirty water as he fell backward, hauling on the club. He pulled his

assailant in after him. There was a brief squawk of anger and surprise. The man

was like a water snake in the

klong

.

Durell released the

club. Water resistance made it a poor weapon. But the other man thought he had

wrenched it free and tried to smash it at Durell’s head again. Durell lunged

forward in the water and locked his fingers on the man’s throat.

For one long moment, in

the shadows under the bridge, with the lights and noise of the Chinese quarter

all around them, Durell looked into the other man's eyes.

They were wild, feral,

drugged.

“Cong Hai?” he

gasped.

The man said: “You die,

you die, you die.”

“Maybe.”

He made a knot of bone

out of his middle knuckle and used his other hand to squeeze it into the Cong Hai’s larynx.

The man smashed at his shoulder with the club; but the few inches of water it

had to penetrate weakened the blow. Durell did not relent; he squeezed harder.

His knuckle was like the knot of a garrote. He saw a recognition of death in

the other’s eyes. He heard, above the sound of a Chinese orchestra in the distance,

a wail and a plea for mercy.

He had no mercy.

“You die, you die, you

die,” Durell said.

It took half a minute to

kill the man.

2

HE LET the body drift

down and away, into the mud at the bottom of the klong. He could do

nothing about it. It took all his strength to cling to a strut of the small

bridge overhead, and then, when his breath came back,

he pulled himself,

dripping wet, out of the canal and fell on his back. He watched the hot Asian

sky reel and dance above him in the humid night.

You came close to it,

Samuel, he told himself. Not a very auspicious beginning for the job. Maybe

you’ve been at a desk too long, back in Washington.

Durell was a big man,

with a heavy musculature, controlled by a lithe and easy way of moving. To a

trained observer who watched him cross a room or a street, he would be marked

as dangerous, as one might mark a prowling jungle cat. Yet he could lose

himself in a crowd, except in a town like this, half Thai and the rest

Cambodian, Malay, Chinese, Indonesian; here his American height made him stand

out. The trick then was to twist his uniqueness into something ordinary; he was

an American businessman, according to his identity papers, in search of

contacts among the tea planters in the distant loom of the mountainous Chaines des Cardarnomes.

You played it with awkwardness, eager to please, with just a touch of

condescension for the “natives.” You smiled a lot and pretended not to

understand the swift, wry asides in Annamese or Canton dialects. He

had never mastered Thai very well, although he had a gift for languages and

could maneuver reasonably well in a dozen major and a score of minor dialects.

Not knowing Thai made his pose easier to maintain.

But someone now knew his

real identity.

And this troubled him.

It could get him killed.

Next time, he might meet a more expert and professional assassin.

Durell rolled over and

pushed up and felt water drain from his soaked linen suit, his shirt and shoes.

The night was hot, but he shivered a moment, seeing his image waver

indistinctly in the black waters of the canal. The high keening of a Chinese

song came from a sampan not far of. He saw the dead man briefly, floating

in the water, and something else. With his foot, he hooked onto the long ribbon

and took it up in his hand. It was the dead man’s headband, a peculiar cap

fashioned of Thai silk and ornamented with a band of snakeskin.

Snakes were the symbol,

the method of life, of the Cong Hai. Silent, secret, and venomous, they

were cousins to the V.C. across the peninsula in Vietnam, infiltrating the

jungles and rivers and mountains here on the Gulf of Siam as sinuously, as the

snakes that were their totems.

Durell shoved the

headband into his wet pocket and stood up. The starry sky reeled around him.

The Chinese lanterns up and down the canal stabbed and winked and jiggled.

Music brayed from the radio, the impossible wail of one of West Europe's

hermaphroditic boy singers. The inane melody fought with the wind bells and

Chinese notes as oil fights with water. Never would the twain meet.

It was a long walk

across the bridge—all of a dozen steps. He staggered like a drunken man. His

head throbbed where the thug had landed his first blow; he had bled a little,

and he wondered about the possibilities of infection from the filthy waters of

the canal. He pushed hard fingers through his thick black hair, touched the

small moustache he had grown for this assignment, tried to adjust his dark

knitted tie into the soggy collar of his drip-dry shirt. His shoes squelched

with each step. A band of running Chinese boys broke around him like a sudden

torrent breaking around a rock; they came and went with a bubble and spray of

Cantonese, laughing at the drunken white man. Good enough. If he met a cop, he

could always Say he’d had too much rice wine at Mama Foo’s and fallen into the

canal.

Until they found

the dead man.

Major Muong, of the

Thai Security people, wouldn’t like that at all.

But first things first.

He’d come here after Anna-Marie Danat, and the last he’d seen of her was

when she went through the red gateway of that big house ahead. To judge from

the expansive compound walls, the solid tiles of the roof, the fish fertility

symbols, it seemed to be the house of a reasonably wealthy Chinese merchant.

The dead man might have

had some friends nearby, and Durell, heading for the house, exercised caution

and kept his hand on the snubby-barreled .38 S&W in its underarm

holster. He looked as if he were scratching his chest. But anger and chagrin at

losing Anna-Marie—and almost losing his life-—-made him a walking time bomb.

But no one triggered an

explosion.