Atlantis Beneath the Ice (7 page)

Read Atlantis Beneath the Ice Online

Authors: Rand Flem-Ath

The German-American anthropologist Franz Boas (1858–1942) traced the mythology of the Ute to the Canadian province of British Columbia,

2

where the mythological trail connected the Utes with the Kutenai and in turn the Okanagan. The Kutenai occupy territory encompassing parts of British Columbia, Alberta, Washington, Idaho, and Montana. Like the Ute, the Kutenai speak of a great fire that erupted over the earth when the sun was struck by an arrow. “Coyote is envious, and shoots the sun at sunrise. His arrows catch fire, fall down, and set fire to the grass.”

3

And the Kutenai speak of the fear they have that the world will come to an end when the sky loses its stability. “The

Kutenai look for Polaris (the North Star) every night. Should it not be in place, the end of the world is imminent.”

4

Little is known of the origin of the Kutenai.

5

They often have wavy hair, light brown skin, and slight beards.

6

Their neighbors in the plains, the Blackfoot, gave them the name Kutenai, Blackfoot for “white men.”

7

Boas believed that the Kutenai’s mythology linked them with their neighbors to the west, the Okanagan.

8

The Okanagan called the Kutenai

skelsa’ulk,

meaning “water people.”

9

In 1886, the American historian Hubert Howe Bancroft (1832– 1918) related the Okanagan myth of their lost island paradise of Samah-tumi-whoo-lah.

Long, long ago, when the sun was young and no bigger than a star, there was an island far off in the middle of the ocean. It was called Samah-tumi-whoo-lah, meaning White Man’s Island. On it lived a race of giants—white giants. Their ruler was a tall white woman called Scomalt. . . . She could create whatever she wished.

For many years the white giants lived at peace, but at last they quarreled amongst themselves. Quarreling grew into war. The noise of battle was heard, and many people were killed. Scomalt was made very, very angry . . . she drove the wicked giants to one end of the White Man’s Island. When they were gathered together in one place, she broke off the piece of land and pushed it into the sea. For many days the floating island drifted on the water, tossed by waves and wind. All the people on it died except one man and one woman.

Seeing that their island was about to sink they built a canoe [and] . . . after paddling for many days and nights, they came to some islands. They steered their way through them and at last reached the mainland.

10

The Okanagan and the Ute feared any dramatic change in the heavens as an ominous portent of another great flood. The fear that the sun might once again wander or the sky might fall became an obsession.

The Ute related, “Some think the sky is supported by one big cottonwood tree in the west and another in the east; if either get rotten, it may break and the sky would fall down, killing everybody.”

11

And the Okanagan believed that in a time to come the “lakes will melt the foundations of the world, and the rivers will cut the world loose. Then it will float as the island did many suns and snows ago. That will be the end of the world.”

12

We can barely imagine the power of the tsunamis that rolled across the earth at this time. Shipboard survivors who had escaped the doomed continent could not escape the sight of successive tidal waves destroying their homeland. It would seem to them that Atlantis had vanished beneath the ocean. This misperception distorted the fact that it was the ocean rising—not the land sinking. Atlantis never actually sank beneath the ocean. The survivors were long gone when the tidal waves subsided and the land was once again visible. But their traumatic memory of a sinking island was passed from generation to generation.

As we move south we encounter the Washo of western Nevada, who are famous for their decorative basketry. They live on the eastern flank of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The tribe was always small, never overhunting the earth. They ranged from a population of 900 in 1859 to just over 800 in 1980. In earlier times, their numbers may have reached 1,500.

13

They are a solitary people who tell a tale of a time, long ago, when the mountains shook with volcanoes and “so great was the heat of the blazing mountains that the very stars melted and fell.”

14

Along the Gila and Salt River valleys of Arizona live the remnants of the A’a’tam tribe, who have been misnamed by outsiders not once, but twice. Because one Italian explorer sailing under the Spanish flag in 1492 didn’t know where he was, the entire native population of the Americas was christened, wrongly, Indians. And when the early missionaries demanded that the A’a’tam tribe identify themselves, they refused, answering in their native tongue with the single word

pima,

meaning “no.” From this exchange a misunderstanding arose that remains to this day. The missionaries took the “pima” response as an answer to their

question rather than a refusal to cooperate, and so the tribe came to be known as the Pima.

15

In fact, A’a’tam means “people.” Part of the A’a’tam history was carried across the centuries in an age-old myth of a Great Flood that had once overwhelmed the earth. Their tale of the Flood included an event absent from the frontiersmen’s Bible. Using the symbolism of a magical baby created by an evil deity, the myth told how the screaming child “shook the earth,” catapulting the world into the horrors of the Great Flood.

16

The A’a’tam now feared that the sky was insecure. Corrective measures were called for, and the Earth Doctor created a gray spider that spun a huge web around the edges of the sky and the earth to hold them secure. Even with these protective measures the fear remained that the fragile web might break, releasing the sky and causing the earth to tremble.

17

In 1849, the California gold rush brought fortune seekers streaming across the Rocky Mountains to the West Coast, home of the Cahto. Ten years later, the pioneers of Mendocino County in northwestern California killed thirty-two Cahto because they took some livestock belonging to the whites. These thirty-two men represented more than 6 percent of the Cahto’s population. To put this tragedy in perspective, we can imagine the havoc wreaked today if the populations of New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles were suddenly murdered by some alien force. The Cahto never recovered. By 1910, 90 percent of the population was dead.

The mythology of the Cahto stretched back nearly twelve thousand years to the time of the last earth crust displacement. Through this legacy we learn of the catapulting events in California at the time of the Great Flood. “The sky fell. The land was not. For a very great distance there was no land. The waters of the ocean came together. Animals of all kinds drowned.”

18

The original title of this book paid tribute to the Cahto, who poetically recalled the Flood as a time

when the sky fell.

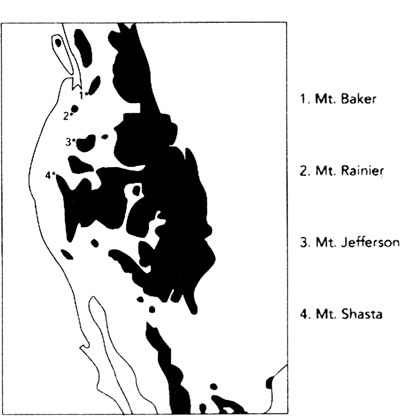

American native mythology identifies four westerly mountains tied to the aftermath of a Great Flood (see

figure 3.1

on page 44). All four mountains are 1,800 meters or higher above sea level. At the time of the Great Flood these mountains at the western extremity of North America would have been the first hope for those survivors of the lost island paradise who had traveled so far across an endless ocean.

Figure 3.1.

First Nations myths honor four mountains as sites of ancestral survival after the Great Flood. These sites suggest the ancestors arrived from the Pacific.

The native people of Washington and Oregon claim that their ancestors arrived in great canoes and disembarked on Mount Baker

19

and Mount Jefferson.

20

They believed that Mount Rainier

21

was the refuge of those who were saved after the wicked of the earth were destroyed in a Great Flood. The Shasta of northern California tell of a time when the sun fell from its normal course.

22

A separate myth relates how Mount Shasta saved their ancestors from the Deluge.

23

On the opposite side of North America lies another great mountain chain, the Appalachians. There, also, tales were told of terrifying solar changes, massive floods, and the survivors of these catastrophes.

The lush green forests of the southern tip of the Appalachian Mountains were once the home of the Cherokee. In the early nineteenth century, a Cherokee named Sequoya created an alphabet for his language. He left a rich legacy of myths transcribed from his people’s oral tradition. In one myth the Flood is attributed to the uncontrollable tears of the sun goddess. It was said that she hated people and cursed them with a great drought. In desperation the Cherokee elders consulted the “Little Men,” whom they regarded as gods. The Little Men decreed that the Cherokees’ only hope of survival was to

kill the sun.

Magical snakes were prepared to deal a deathblow to the sun goddess. But a tragic mistake was made, and her daughter, the moon, was struck instead.

When the Sun found her daughter dead, she went into the house and grieved, and the people did not die any more, but now the world was dark all the time, because the Sun would not come out.

They went again to the Little Men, and told them if they wanted the Sun to come out again they must bring back her daughter. . . . [Seven men went to the ghost country and retrieved the moon but on the return journey she died again. The sun-goddess cried and wept . . .]

until her tears made a flood

upon the earth,

and the people were afraid the world would be drowned.

24

(italics added)

The Cherokee, like the Ute and Okanagan tribes, held a dark prophecy of how the world would end. “The earth is a great island floating in a sea of water, and suspended at each of the four cardinal points by a cord hanging down from the sky vault, which is of solid rock. When the world grows old and worn out, the people will die and the cords will break and let the earth sink into the ocean, and all will be water again.

25

Despite the fact that they both lived in mountain ranges that lay far from the ocean, the Cherokee and Okanagan both associated the mythological Flood with

an island.

For the Okanagan this island lay “far off in the middle of the ocean.” For the Cherokee the myth of the “great

island floating in a sea” contains clues to the lost land. “There is another world under this, and it is like ours in everything—animals, plants, and people—save that the seasons are different.”

26

There is, in fact, just such an island in the middle of the ocean with a climate opposite to that of the northern hemisphere (see

figure 3.2

). The island continent of Antarctica was partially ice free before the last earth crust displacement. Was it the doomed island of Okanagan and Cherokee mythology?

The people of Central and South America also hold rich mythologies about the lost island paradise and its destruction in a Great Flood.

Figure 3.2.

Antarctica is an island in the middle of the ocean, just like the lost land of Okanagan mythology. And like the floating disc of Cherokee mythology, Antarctica would have experienced seasons opposite to those of North America. The formerly temperate parts of Antarctica may have been, before the last earth crust displacement, the lost island paradise of Okanagan and Cherokee mythology.

The Ipurina of northwestern Brazil retain one of the most elegant depictions of the disaster. Their myth states, “Long ago the Earth was overwhelmed by a hot flood. This took place when the sun, a cauldron of boiling water, tipped over.”

27

Further south, the Spanish conquistadors assumed after their sweeping victories in Mexico and Peru that Chile would be another easy target. Santiago, the Spanish capital, was founded in February 1541 by Pedro de Valdiva, the first Spanish governor. Six months later the city was destroyed by the native people of Chile, the Araucanians, who launched a war that continued for four centuries. Here was a tribe so valiant that they would fight for generations rather than submit to slavery. But even these brave people trembled before a traumatic memory. “The Flood was the result of a volcanic eruption accompanied by a violent earthquake, and whenever there is an earthquake the natives rush to the high mountains. They are afraid that after the earthquake the sea may again drown the world.”

28