Aunt Effie's Ark (10 page)

Authors: Jack Lasenby

Even the powerful gorillas couldn't lift the foot of the mast off Peter's hand. The elephant tried, but shook his head. The ship lay on her starboard side, the mast askew. Down in the bilges, the water kept rising

towards

Peter's mouth.

The elephant hung on to the bulwark with his trunk and leaned out to port to try and bring the ship back. We ran around the deck screaming and getting in each other's way.

“Man the pumps!” Marie shouted to the gorillas. “Rig sheerlegs!” she ordered us.

From down in the bilges, Peter yelled, “Keep your fingers crossed!” The water was rising over his mouth so we only heard, “Bubble bubble bubble!”

The gorillas pumped manfully so water squirted over the sides, but down in the bilges it kept rising. Peter had to close his mouth and breathe through his nose.

“I know what the trouble is!” said Daisy and ran into the hold.

The rest of us screamed, tripped over each other,

and hung a block from the sheerlegs. Our fingers were all crossed thumbs as we reeved a wire rope through the block and took a turn around the capstan. Casey and Jared ran down below. Casey held Peter's nose closed as the water rose over it, and Jared stuck a straw in his mouth so he could breathe. It worked, but the water kept rising towards his eyes.

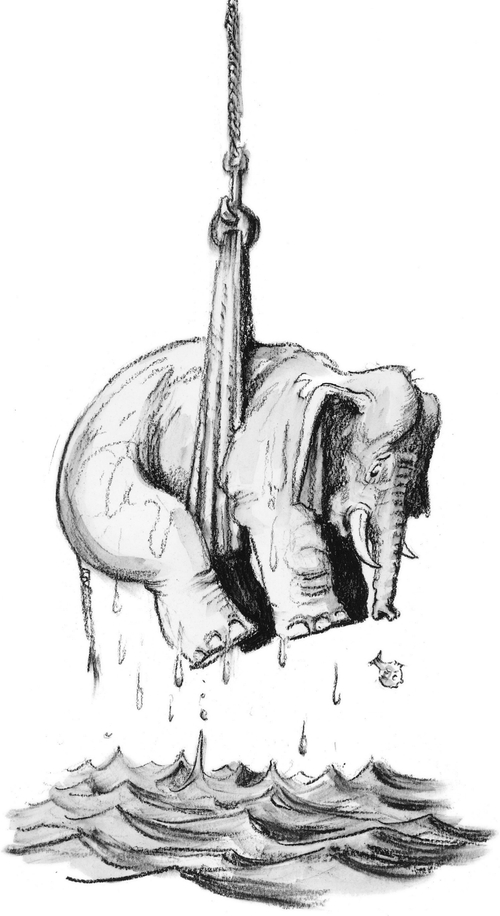

“Bring a longer straw!” Casey yelled. And just then the ship rolled back to port, and settled on an even keel. The elephant let go with his trunk so he could squeal and fell into the sea. “Help!” he trumpeted. “Elephant overboard!”

Down below, Peter cheered as the heel of the mast lifted long enough for him to pull out his squashed right hand and slip in the sovereign with his left. We heard the satisfying snick as the mast slid into position, and the keel took the strain. Peter came on deck spluttering. When he'd opened his mouth to cheer, the water had rushed inside and gone down the wrong way. We patted him on his back, and it spurted out of his mouth again.

“I'll bet your sovereign's squashed flat!” Jazz said.

“So's my right hand.” We stared at his flattened right hand and lined up to take turns shaking it and

measuring

it against our own. Peter always had to buy two pairs of gloves after that. So he could get an ordinary glove for the left hand, and an enormous one for the right hand.

“Man overboard!”

“We forgot the elephant!” we screamed. Our

sheerlegs

turned out handy after all. We passed a broad strop under the elephant's belly and swung him aboard. He shook himself so water showered over us.

“It's not fair,” he said. “You took no notice when I shouted, âElephant overboard!' but you came running when I called, âMan overboard!' It's not fair!” he said again. We hung our heads and drew circles on the deck with our toes.

“We're sorry,” we whispered.

“I forgive you!” said the elephant who had a

generous

nature. He emptied the water out of his trunk and we found he'd caught enough fish to feed everyone aboard.

After a good meal, Peter said, “We still don't know what put the ship over on her side. Let's find the leak!” He led us down to the hold where Daisy was still giving the gander a piece of her mind.

She had caught him chasing the cows from one side to the other. That's what had made the ship roll, and the mast slip. Daisy had got the cows back amidships so the ship settled on an even keel, and the mast rolled off Peter's hand. But Blossom and Rosie had run into the side of the hull so hard, their horns stuck right through the planks. Blossom's horns had broken off and plugged their holes. One of Rosie's, though, had punched a hole then pulled out again. That's where the water was gushing in.

Daisy gave the gander a good shake. “Hold your breath!” she ordered, and stuck his head into the hole. Peter filled Blossom's broken-off horns with caulking and tar. He found a wooden plug and wrapped it with tarred felt. “Now!” he said. Daisy pulled out the gander's head, and Peter hammered the plug home with a

mallet

. A drop of water squeezed through. Peter hammered the plug again, and the leak stopped.

“You can lay off the gander, Daisy,” Peter said. “He won't cause any more trouble.”

The gander nodded gratefully. He had tears in his eyes from being shaken silly, getting a piece of Daisy's mind, and having his head stuck into the hole. We all felt sorry for him, but we said Daisy had acted decisively and saved Peter from drowning.

Marie rasped smooth the stumps of Blossom's horns. Fortunately they didn't bleed much, and Blossom said it didn't hurt except for a slight headache. For a while she looked funny without her horns, then it became fashionable, and all the other cows wanted their horns cut off, too.

“Why is Ann crying?” asked Peter. “What's the

matter

?”

“I told you, but you were busy drowning in the bilges, and nobody else would listen to me,” Ann wept. “Something's sucked all the blood out of this sheep!”

Horrified, we stared at the whitest sheep we'd ever seen. Its ears, face, and feet were as white as its wool. When it opened its mouth and tried to baa, we saw its tongue was white, too.

Peter parted the wool at its throat, and we saw two puncture marks. “Something's sucked its blood out through these holes,” he said.

“It'll die if it doesn't get a blood transfusion!” said Marie.

“We haven't got a medical laboratory,” Peter said. For once, he and Marie didn't know what to do.

“We know a place!” The little ones led us to another cabin they'd found, a medical laboratory with all the gear for giving blood transfusions. Marie pumped fresh

blood through the puncture marks into the empty sheep. We could hear it filling up like a bottle: “

Glug-glug-glug

-glug-glug-glug-glug!” The white sheep turned a healthy pink colour under its wool. “Baa!” it said, and its tongue was red again. “Baa!”

“It's saying, âThank you',” Jessie told Marie.

Back in the skillion, an emotional hogget named Cecil told us, “We heard baaing but took no notice because Alwyn had taught the lambs a game he called, âCrying Wolf!' They'd been playing it all morning. Then we found poor, little Stephanotis, all white and anaemic!” Cecil broke down and wept, and we all wept noisily with him.

“Well, she's all right now,” said Peter.

“It must be those gluttonous wolves!” cried Daisy.

“I told you!” said Marie, “They're timber-wolves! And they brought their own wood!”

“Perhaps there's another wolf somewhere aboard the ship!” said Victor. He always loved a mystery, but his voice shook with fear at the thought that somewhere about the ship, in one of the many cabins we hadn't searched, along one of the corridors, or up one of the companionways, a gluttonous wolf was licking his lips and planning to suck somebody else's blood. We

huddled

together in a mob just like the sheep â except that we didn't baa, and we kept the little ones in the middle.

Hubert arranged a roster amongst the bulls so that there were always at least two of them patrolling the hold and keeping watch. Still keeping the little ones in the middle, we shuffled up the ship's ladders and

companionways

to the upper deck to finish rigging the ship.

With the mainmast up, stepping the foremast was

easy. We bowsed down the stays, swigged taut the shrouds, ran out the jib-boom, and rigged the bobstay and dolphin-striker. We sent up the topmasts and belted the fids through their holes and across the trestle-trees to keep them in place. We raised and crossed the yards. We hoisted the Singer sewing machine on deck and took turns pedalling it while Marie sewed the sails. Lastly we bent on the canvas. And we did it all with our fingers crossed.

“There's something we've forgotten,” said Marie.

“I know!” Peter grinned. “A rudder!” He showed her a kauri ricker he'd been adzing for a rudder post. While we built the rudder blade, Jazz and David forged pintles and gudgeons in the blacksmith's shop. Using a purchase off the end of the spanker boom, we lowered the rudder over the transom. It was tricky work,

hanging

out over the water while holding on with one hand, getting everything lined up, dropping the pintles on the rudder post into their gudgeons on the stern post, and keeping our fingers crossed all the time.

At first we tried steering with a tiller, but the ship had so much weather helm, the elephant and twenty powerful gorillas were swept off their feet. Jazz built a yoke and fitted it over the rudder head, Peter and Bryce rigged a system of chains, and Marie and Colleen built a mahogany wheel. Even then it took two gorilllas to man the wheel.

Everything we'd learned building and sailing the Margery Daw helped, but it took us several months to rig Aunt Effie's Ark. You try hanging on with one hand while sending up a topmast with your other hand, and still keeping your fingers crossed.

We had to wear ship to bring her around. Aunt

Effie's

Ark wasn't a great performer up into the wind. “You want fore-and-aft rig for that,” said Marie, “like a schooner. Aunt Effie's Ark's meant to save lives, not to win the Americas Cup.”

“Are we going to sail across the Gulf again?” Lizzie asked.

“I've been thinking about that,” said Peter. “We'll cross the Gulf again on the Margery Daw, but we'll never have another chance to sail over the Mamakus and Rotorua. We could sail over Whaka! Have you ever wondered what a geyser looks like under a flood?”

“If we sail over Rotorua, can we we sail a bit further south and see the Kaingaroa Forest?” asked David.

“If we sail over the Kaingaroa Forest,” asked Lizzie, “can we sail a bit further south and see the Vast

Untrodden

Ureweras?”

“Arrgh!” Daisy shrieked, and fell to the deck in one of her swounds.

We hadn't seen the Tattooed Wolf since the day he ate our snowman. For months we never said his name aloud, kept our fingers crossed, and pretended there was no such person. We didn't say, but we hoped he was drowned in the floods.

We'd also been pretending there was no such place as the Vast Untrodden Ureweras. Aunt Effie and the Prime Minister had warned us that gluttonous wolves, grizzled bears, and man-eating rhinoceroses came down from there in hard winters. We were careful never to say their names aloud either.

“Will we see the Vast Untrodden Ureweras?” Lizzie repeated just as Daisy woke up. “It's bad luck to say that

name!” Daisy shrieked, kicked her heels on the deck, and swooned again. The rest of us spat over the side to keep away the bad luck, held our breath, and kept our fingers crossed. We looked at Peter and Marie â for them to say something.

“I don't think they'll be flooded,” said Peter, and his voice shook. “They're much higher, but we'll see.”

“I want to see the Horomanga River, the

Hopuruahine

Hut, and Harry Wakatipu.” Lizzie looked at her crossed fingers as if trying to remember something. “Oh, and I want to see Barry Crump!”

It was just then that Hubert sent up a young horse with a message to say that a turkey was looking ill. We ran below and stood around the turkeys' pen. Pale and very still, one of the old gobblers lay on his side. Instead of being bright red, his long crooked nose, his floppy comb, and his lobed wattles were all white.

“Something's sucked out his blood, too!” said Peter. “I don't know who's responsible, but it's not the work of a gluttonous wolf. Wolves don't leave puncture marks in the neck.”

We gave the white turkey a transfusion of new blood, and returned him to the hold where he was soon

strutting

and gobbling as red-faced as the others. Since the bull patrols thought it was below their dignity to keep an eye on the poultry, Peter appointed a cocky little bantam rooster to guard them.

Back on deck, we set studding-sails and sailed south over Te Poi and Okoroire. About midday, we came alongside a drifting school and rescued a whole classroom of kids. Only their teacher was missing, and they said they didn't know what had happened to her.

“Did those children eat their teacher?” Lizzie asked.

“Perhaps they sucked her blood!” said Alwyn, and Daisy fell into another of her swounds.

We didn't believe a word of it, of course, but kept our hands away from the children as we gave them breakfast next morning. Marie and Peter noticed and scolded us. “You should know better than to believe anything Alwyn says⦔

“Says Alwyn anything,” Alwyn whispered just loud enough to make us all laugh.

We sailed on over the Mamakus and picked up five

forestry

workers who'd been stranded several months in the top of a tall tree with nothing to eat but pine cones.

Two linesmen marooned up a telegraph pole were delighted to see us. They'd had nothing to eat but their leather belts, and were very thin. Holding on to their trousers to keep them up, the linesmen guided us to a pilot who'd crash-landed in the top of a macrocarpa tree because all the airports were flooded.

“About time!” shouted the pilot. She spoke very fast. “Why did it take you so long to rescue me? My name is Mean Fatten! I'm famous, and I've been sitting in the top of this tree, waving my arms and shouting, âHelp!' for a fortnight. And all this time I've had nothing to eat but macrocarpa nuts! I don't know what the police can be thinking of!”

Marie put a running bowline in the end of a halyard and tossed it to her. “Stick your head and shoulders through the loop and pull it tight under your arms!”

The two linesmen let go their trousers, pulled the halyard, and swung the angry pilot aboard. The

running

bowline tightened under her arms until her eyes

bulged.

“Why are you still wearing flying goggles?” Alwyn asked.

“Just you wait till I see the Prime Minister,” Mean Fatten shouted at Marie. “I'll tell her you tried to strangle me!”

Her eyes bulged even further as she looked at the linesmen. “Adjust your dress at once!” she shouted.

“Once at dress your adjust,” said Alwyn. Mean

Fatten

was still wearing her flying helmet, so perhaps she didn't hear him. The linesmen pulled up their trousers.

“Why didn't you salute when I came aboard?” cried Mean Fatten. The linesmen let go their trousers to

salute

her, and they fell down again. The pilot squawked, looked at us and demanded, “Why are you children barefooted? Tuck in your shirt! Did you brush your teeth this morning?”

“Morning this teeth your brush you did?” Alwyn asked her.

“How dare you?”

“You dare how?”

Mean Fatten danced with rage, and Alwyn danced back at her. She sounded so like Daisy, we knew we must never let them meet, so Marie gave her a berth in the maggots' cabin.

South we sailed, the Mamakus dropping away under us in the deep water. Off the top of Ngongotaha

Mountain

we swung aboard a starving mountain bicyclist who had eaten his tyres. He was having trouble with bits of rubber stuck between his teeth. We sailed on, looking down through the flood on something blue and flat as a dinner plate.

“Lake Rotorua!” said Jazz.

We took in our studding-sails, cruised above

Tutanekai

Street, and saw the shops full of people caught by the floods. They stood staring out the windows and waiting for the water to go down. South we sailed out the Whaka Road, looked down through the water, and saw the mud pools still bubbling. Alwyn poked out his tongue and called, “Plop! Plop!” but the mud pools bubbled slowly and took no notice.

Pohutu Geyser blossomed white beneath our keel. Peter dipped boiling water over the side and made a billy of tea for the watch on deck.

As we headed south over the Whakarewarewa State Forest, David stared down, fascinated by the pine trees. It seemed ages before we got clear of them and rescued a busload of Japanese tourists stranded on top of Mount Tarawera.

“Please descend from your coach,” Daisy shouted at them.

“What's a coach?” asked Lizzie.

“It sounds nicer than saying bus,” Daisy smiled. “Welcome aboard our humble vessel,” she greeted the hissing travellers. Then she saw what they were

carrying

. Instead of starving to death, the Japanese tourists had survived without food by taking photographs of each other and eating them.

“Tastes just like whale steak!” they said, munching the photographs, and offered some to Daisy who fell to the deck in another of her swounds.

We showed the Japanese tourists to comfortable cabins where they had plenty to eat and could stop taking photographs of each other. Later we found the

ill-mannered pilot, Mean Fatten, had confiscated their cameras, but Peter made her give them back. There were few squabbles on Aunt Effie's Ark. Most people fitted in, no trouble. There was tucker galore for

everyone

, lots of bunks, galleys, and dunnies â what we now called the heads.

“Aunt Effie had it all thought out,” said Marie.

Pine trees look splendid from the ground but

become

tiresome when you sail for weeks, looking down on long straight lines of them that go on and on and on. David had thought of running away from school to work in the pines, but changed his mind when he saw the size of the Kaingaroa Forest.

“How do you find your way?” he asked an alert old fire-watcher we rescued off the roof of his lookout on top of Rainbow Mountain.

The alert old fire-watcher shook his head. “The Kaingaroa is full of lost foresters who can't find their way out because all pine trees look the same. After a year or two, anyone working in the pines starts to look like one himself. Some of the lost foresters even grow whiskers like pine needles and put down roots.” Just to show us, he threw a cone at a pine tree nearby.

“Here, watch it!” shouted the pine tree.

“See what I mean?”

“What's that blue wall in the distance?” Lizzie asked the alert old fire-watcher.

“That's the bush, what us jokers who work in the pines call âthe native'. That blue wall, that's the

beginning

of the Vast Untrodden Ureweras.⦔ At the name, Daisy fell in one of her deepest swounds.

“That's where we're going!” Lizzie told him.

“Then I'm getting off!” The alert old fire-watcher trembled. “The Vast Untrodden Ureweras are full of gluttonous wolves, grizzled bears, and man-eating rhinoceroses. The deer cullers are supposed to hunt them, but they're too busy playing poker for tins of condensed milk. You're not taking me there!” He dived over the side, swam back, and sat on the roof of his lookout again. As we sailed towards the Northern Boundary, he shouted, “And that silvery-blue cloud in the distance, higher up and further back behind the Vast Untrodden Ureweras, that's the Grim Inscrutable Ureweras, the home of the dreaded Harry Wakatipuâ¦!”

“People who work in the pines are usually scared stiff of the bush â what they call âthe native',” said Jack.

“Will we be scared of the bush?” asked Lizzie.

“We don't work in the pines. Besides, I know the jokers who work up in the bush.”

“I don't,” said Lizzie.

“You weren't born when I worked up in the bush with my mates,” Jack said. “But you'll remember them when you see them.”

We sailed down Middle Road, over Murupara, the Rangitaiki and the Whirinaki Rivers. “We used to sing a song,” said Jack.

Just two rivers I don't like, Whirinaki and Rangitaik,

I'm moving on, I'll soon be goneâ¦

Too wet and wide for my old hide, I'm moving on.

We looked down through the water and saw a yellow AA sign that said Troutbeck Road. We followed it out through Galatea, and turned right up the Horomanga

Valley. Range after range after range of blue mountains stood up to their shoulders in the flood, as we threaded our way between.

“Is this the Vast Untroddens?” asked Jessie. Jack nodded and started to say something, but there was a terrifying bellow. It was one of the bull patrols shouting, “Help! The blood-sucker has struck again!”

We ran below. A very pale monkey lay where it had fallen to the floor of its cabin. It had been sucked dry of its blood through two fang marks in the neck. Marie gave it a blood transfusion, and it sat up and whispered something to Alwyn.

“It says it went to sleep hanging from the light cord in the middle of the cabin,” he told us. “

Whatever

sucked its blood must have crawled up the wall, across the ceiling, and down the light cord to reach the monkey.”

“Oh, talk sense!” Daisy told him.

“Sense talk oh!”

“Say that again,” Marie said to Alwyn.

“Say that again,” he repeated.

“No! What you said before.”

“Whatever sucked its blood must have crawled up the wall, across the ceiling, and down the light cord to reach the monkey.”

“Hmm!” said Marie. “That might be a clueâ¦.”

By now we had bull patrols keeping watch on each deck. We could not understand how the blood-sucking horror could have dodged them to reach the monkey. And how had it escaped without leaving any tracks?

“I'm sure of one thing!” Marie said. “It's not one of the timber-wolves. We've had a gorilla standing guard

over their door for the last three days.”

“And,” said Peter, “we've searched for scent with those bloodhounds Ann found. It leaves no trace for them to follow.”

“You don't thinkâ” said Victor, “âthe murderer is one of the bloodhounds?”

“Certainly not!” said Ann. “Bloodhounds drink only water. They can't stand the smell of blood. That's why they're so good at tracking it.”

“What do we know?” asked Marie and she answered her own question. “We know something sucked the blood out of a sheep, a turkey, and a monkey. The sheep was standing in its pen in the skillion. The turkey was on its roost. The monkey was asleep, hanging from a light cord. Whoever the blood-sucker is, it attacks at night, leaves no scent, and no tracks.”

“That means,” said David, who was logical, “the blood-sucker must be able to fly. It's elementary! We are looking for a winged vampire!”

We all shrieked, “A winged vampire!”

“A winged vampire,” David repeated, “leaves no tracks and no scent on the ground. It can suck the blood out of a sheep standing on the deck, or a

monkey

hanging from a light cord. Nobody's safe from a winged vampire.”

“Arrgh!” we all screamed.

“What's more,” said David, “vampires love the taste of blood!” There was a little cry, and Daisy swooned again.

“The only protection against a vampire,” said Peter, “is a suit of armour.”

“Aunt Effie thought of everything,” said Marie.

“There are enough suits of armour for everyone in her wardrobe.”

We buckled on greaves, cuirasses, and helmets like upturned buckets. Through the visors we could see only a slot of light straight ahead.

Marie waved her sword. “Search the ship and find the vampire before it strikes again!”

Climbing up and down ships' ladders and

companionways

in a suit of armour is difficult. When you fall over, it takes several other people to get you on to your feet again, and they have to take off their armour first. Then they have to put it on again. We tumbled and clanked through the ship from bow to stern.

With that surprising courage of hers, Daisy entered a cabin alone. It was full of winged vampires who gnashed their fangs and crawled all over her, trying to suck her blood. Luckily, their fangs weren't long enough to go through her steel armour. When Daisy realised what was happening, she gave them a piece of her mind. By the time we rushed to help, the vampires had had enough. Shrieking for mercy, they flapped their wings like black sheets, flew out the porthole, and disappeared like a black cloud.

“When I worked in the bush,” said Jack, “we used to call them mosquitoes. I lost several mates to them. Of course, we didn't have Daisy in those days.”

We cheered Daisy, forgetting we still had our

helmets

on. Our ears started working again after several days.

We sailed on up the Horomanga Valley. Near some poplars on a clearing, we looked down through the water and saw an airdrop camp. Somebody had burnt

a hole in the roof of the tent and repaired it with a plastic bag. We could see some men around a table made out of an ammunition case, playing poker for tins of condensed milk.

“Why have they got antlers growing out of their ears?” asked Jessie.

“They're deer cullers,” Jazz told her. “After years of eating nothing but venison and condensed milk, they all grow antlers. The one dealing off the bottom of the pack, that's Barry Crump! I've read all his books.”

“I remember him!” said Lizzie.

“I don't think you were born when he was still alive,” Becky told her.

“It's not fair,” said Lizzie, “being young.”

“The one in bare feet,” said Jazz, “that's Dunc, the famous top shooter! See how his legs are worn short from all the climbing and tramping? And look at his old .303! See how the barrel's worn short from all the shooting?

“Look at his trigger,” said Jazz. “How worn it is.” It was true: Dunc's trigger had been pulled so many times it was worn thin as a whisker.

“That's a real hair trigger!” Jack told Lizzie. “The good-looking one next to Dunc, that's Bonehead.”

“Why's he called Bonehead?”

“Because he's always butting it against

immoveable

forces. And that's his mate, Barry Mercer next to him. Then Stew Coupar. Jimmy Clendon, only he calls himself Jimmy Tinana now. Tom Cookson, Bob Young. And the one winning all the condensed milk, that's Rex Newton.”

“I remember their faces. But how do you know

their names?”

“They were my mates. They used to come to our house,” Jack told Lizzie, “before you were born. Barry Crump was on telly.”

“That one at the back,” Lizzie said, “he looks like you!”

Jack looked down through the water at the inside of the airdrop camp. “It's me, all right! Back when I was young. In the 1950s.”

“How can you be down there and up here at the same time?”

Jack shook his head. “I'll have to think about that.” He ran to the stern and looked down through the water at himself and his old mates until we sailed on and their tent disappeared.