Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe (7 page)

Read Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe Online

Authors: Ian Castle

Tags: #History, #Europe, #France, #Military, #World, #Reference, #Atlases & Maps, #Historical, #Travel, #Czech Republic, #General, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #19th Century, #Atlases, #HISTORY / Modern / 19th Century

When the time came for the leading Russian army to march to war in 1805 it relied heavily on the Austrians to make good their great shortage in transport and supplies. Yet on the eve of war the Austrians faced numerous problems of their own.

Archduke Charles (Erzherzog Karl), a younger brother of the kaiser, and the man charged with the responsibility of reforming the Austrian military system after defeat in 1800, was well aware of the enormity of the task. As such, he felt an extended period of peace was absolutely essential, and he vehemently opposed those who sought an early return to conflict. He began with an extensive overhaul of the archaic administration of the army, but this earned him much criticism from those who felt he should focus his attention on problems within the structure and organisation of the armed forces themselves. Yet despite a massive reduction in the military budget of 60 per cent between 1801 and 1804, Charles managed to introduce improvements. The first steps towards a permanent General Staff were taken with the appointment of FML Duka as Quartermaster General in March 1801, a title normally conferred only in wartime, along with a number of officers solely allocated to staff tasks. At a regimental level, junior officers were poorly paid, with the consequence that the army no longer offered an attractive career for the sons of the upper nobility. The necessity to widen the recruiting base of the officer class meant a further drop in the generally low educational standard they attained, but Charles pressed on with efforts to improve low morale and encourage esprit de corps.

Recruitment to the army was in the main by conscription, but so many individuals were exempt – or avoided selection – that only additional voluntary enlistment kept the numbers up. To help prevent large numbers ‘disappearing’ rather than taking their place in the ranks, Charles reduced enlistment terms from twenty-five to ten years in the infantry, twelve in the cavalry and fourteen in the artillery and engineers. The very nature of the vast Habsburg Empire meant that the army was multi-national, drawing Germans, Hungarians, Italians, Walloons, Poles, Croats, Serbs and many smaller eastern ethnic groups together to fight for the kaiser.

Economic restrictions made it necessary for the army to house many of its troops in the far-flung corners of the empire, where living was cheaper. Others, after basic training, spent long periods at home on unpaid furlough, limiting the opportunity for regular large-scale manoeuvres. When these manoeuvres did take place they often drew criticism from Charles’s opponents. One commented that they highlighted the ‘capabilities of the rank and file and the total ineptitude of the officers’.

4

In 1803 joint foreign ministers, Franz Colloredo and Johann Cobenzl, felt convinced of the necessity of a new alliance with Russia, but faced constant opposition from Archduke Charles. Besides the unprepared state of the army, Charles also voiced his doubts over Russia’s reliability and the likelihood of any British intervention in Central Europe. Without these, he argued, Austria would once again risk facing the brunt of any French attack alone. Frustrated by Charles’s negative views, Colloredo and Cobenzl began to undermine his position. In doing so, they introduced a retired army officer, FML Karl Leiberich Mack, to present an opposing view on the state of the army. Mack’s disastrous period in command of the Neapolitan army in 1798 had tarnished a well-respected earlier career, during which he earned widespread admiration in the campaigns in the Low Countries (1792–1794). But his positive views appealed to the kaiser, who drew increasingly towards this strong faction.

The signing of the treaty between Austria and Russia in 1804, without Charles’s involvement, confirmed the weakening of his position. The pressure against him continued to mount until in April 1805, he was forced to dismiss FML Duka and accept the appointment of FML Mack as the new Quartermaster General, with direct access to the kaiser. Duka, like Charles, maintained it would take six months to bring the army to a war-footing. Mack suggested he needed only two to achieve the same result. As such, Austria only began to mobilise in July 1805: just a few weeks after Mack had introduced major structural changes in the army.

Under Mack’s belated changes all cavalry regiments, whether light or heavy, increased to eight squadrons: a strength previously only maintained by the hussars. This he achieved by reducing squadron strengths to 131 men in heavy and 151 in the light cavalry regiments. However, as with all other nations in 1805, a shortage of horses made it impossible to attain these numbers in the field.

The reorganisation was more dramatic in the infantry. Until 1805 regiments formed three field battalions, each of six companies of fusiliers and one garrison battalion of four companies. In addition, there were two grenadier companies, but these generally fought in combined grenadier battalions. Under Mack’s changes all regiments were authorised to change their establishment to six battalions: four field and one depot battalion of fusiliers and one battalion of grenadiers, each battalion restricted to four companies. However, it seems clear that not all regiments introduced these changes before war commenced in 1805. The frustrations felt by those who did push them through are expressed by an officer who bemoaned the fact that the ‘common soldiers no longer knew their officers and the officers did not know their men.’

5

There was no time for Mack to attempt any last minute reorganisation of the artillery and the great shortages of men, equipment and draught animals ensured that it was woefully understrength when war broke out.

Mack added one final late change. The army would now follow the French example of living from the land. By drastically reducing the amount of baggage accompanying the army, he hoped to see a corresponding improvement in its mobility. But an army that for generations had relied upon a regular food supply on campaign now found itself required to adapt to foraging to boost a meagre daily flour allowance.

Britain, the other main signatory to the Third Coalition, possessed only a small army when compared to the might of Austria and Russia. While she planned to send forces to support the flanking actions of the Allied plans, the joint forces of the kaiser and the tsar would undertake the main thrust of the campaign. But Britain’s contribution was essential to the plans of the coalition. The treaty between the three nations required Austria to raise 250,000 men and Russia 115,000 for the war – and Britain, under Pitt’s leadership, was to subsidise the cost to the tune of £1.25 million per 100,000 men.

6

And so a revitalised and confident French army, under the inspired leadership of the Emperor Napoleon, held aloft their new eagle standards and carried them eastwards into battle for the first time. Against them, the armies of Austria and Russia hastily completed their final preparations and mustered beneath the shared ancient imperial symbol of the double-headed eagle. As these eagles of Europe sharpened their talons, the armies of emperor, kaiser and tsar unfurled their banners and prepared to march across Europe – to glory or ignominy.

____________

*

Dutch proverb.

Chapter 4

‘Every Delay and Indecision Causes Ruin’

*

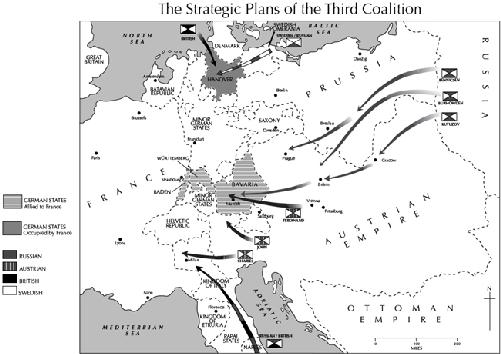

The grand strategic plan conceived by the signatories of the Third Coalition unleashed five separate Allied attacks against France and the territories she occupied. In July 1805, while the diplomats bound their nations together with treaties and protocols, the military men concocted the complex combinations necessary to bring their plans to fruition.

The Russians entrusted their negotiations to the able General Maior Baron Ferdinand Wintzingerode. German-born and having served in the Hessian and Austrian armies before joining the Russian army in 1797, Wintzingerode quickly established himself and was appointed an aide to the tsar in 1802. His experience and knowledge ideally placed him to undertake this important role. For Austria, Mack sat at the negotiating table, along with FML Schwarzenberg, a brave soldier–diplomat and vice president of the Hofkriegsrat, the Imperial War Council. There was no place for Archduke Charles. The plans they hammered out called for a Russian force of about 16,000 men to join the 12,000-strong Swedish garrison of Stralsund on the Baltic coast and drive into Hanover, where, reinforced by British troops, they would press on into Holland. In the south of Europe, as many as 25,000 Russian troops, based on the island of Corfu and at the Black Sea port of Odessa, supported by up to 9,000 British troops from Malta and Gibraltar, would land in the Kingdom of Naples. Then, in conjunction with the Neapolitan army (some 36,000-strong), they were to defeat the French in that region and drive north to support the offensive in Central Europe, where the main thrust of the Allied campaign would take place.

The main Austrian army, under the command of Archduke Charles, was to assemble in north-eastern Italy, behind Verona on the Adige river, from where it could advance into Lombardy and push on Milan. With the French driven back, Charles could then continue through Switzerland, and in conjunction with a second Austrian army on the Danube, press on into France. While

Charles launched his attack, this second army would fulfil more of a holding role. Under the command of the 24-year-old Archduke Ferdinand d’Este, a close relative of the kaiser, this army was to cross the border into Bavaria, gain the support of the Bavarian army and await the arrival of a Russian army, led by General Mikhail Kutuzov. Only then would it join the advance into France. Linking these two Austrian armies was a smaller defensive force located in the mountainous Tirol region between Bavaria and the Austrian provinces in northern Italy, under the command of Charles’ younger brother, the 23-year-old Archduke John. Kutuzov, with a Russian army of 46,000 men was to march with all speed from the western edge of Russia to Braunau on the River Inn, the border between Austria and Bavaria, where it was to regroup. The date for the commencement of Kutuzov’s advance was set for 16 August, but a delay in Wintzingerode’s departure from Vienna officially put the start date back to 20 August.

1

Further to the north, General Bennigsen would advance through Prussia and Bohemia before driving into Franconia (northern Bavaria) at the head of a Russian army of about 40,000 men. From here he could support the attack on Hanover and Holland or align with Kutuzov on the Danube. Another Russian army, 50,000 men on paper and commanded by General Leitenant Buxhöwden, would march later, between Kutuzov and Bennigsen, able to switch to the support of either as circumstances dictated.

There is no doubt that the plan looked impressive, and if it could have been made to work then it would certainly have caused Napoleon problems. But even before the campaign got underway the plans were thrown into confusion. Much of the strength of the plan depended on Prussia joining the coalition and granting permission for Russian troops to march through her territory: but with Prussia resolutely clinging on to her neutrality, permission was not forthcoming.

In Austria, command issues threatened the preparations too. The tsar insisted that when Kutuzov linked with the Austrian forces on the Danube the supreme commander should hold a high dynastic rank. With Archduke Charles destined for Italy, the kaiser assumed the responsibility of this position, but in the meantime, Archduke Ferdinand would remain in command and lead the army into Bavaria. However, Francis then appointed FML Mack as Ferdinand’s chief of staff and handed him secret orders empowering him to override Ferdinand’s military decisions. By this authority Mack became the de facto commander of the army on the Danube. It was a fatal decision, one that would play havoc with the command structure in the coming weeks. Meanwhile, endless diplomatic delays, disputes and negotiations held back the proposed flanking attacks in Hanover and Naples. By the time they got underway it was too late to influence the campaign.

Throughout the spring and early summer of 1805 Napoleon’s agents brought him reports of increasing Austrian military activity in Tirol and northern Italy, as well as in Upper Austria. Alerted to this development he began to woo Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden: their military contingents

would prove useful additions to his army, but more importantly, should war follow, unrestricted passage for his army through their territories would allow him to strike swiftly on the Danube. The pressure on Prussia to form an alliance increased too, with the prize of Hanover on offer in exchange. In return for this territorial expansion, Napoleon required Prussia to mobilise an army on her border with Bohemia to face any Russian incursion. Prussia made soothing noises but determinedly declared her neutrality, nervously veiling the defensive treaty agreed with Russia the previous spring.

Matters intensified in August when reports reached Napoleon that Austrian contractors were openly filling magazines with supplies in Swabia, a region encompassing much of south-west Bavaria and the Black Forest. By 23 August he had heard enough. On that day he despatched a letter to Prussia declaring his intention to march on the Danube and rejoicing ‘at the new bonds which will draw together our states’, before offering the prize of Hanover once again. He well understood the threatening effect a belligerent Prussia would have on the war plans of Austria and the release of his troops currently occupying Hanover would boost the forces available for the war. But Prussia would not sign and continued to affirm neutrality.