Read Avoid Boring People: Lessons From a Life in Science Online

Authors: James D. Watson

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Self-Help, #Life Sciences, #Science, #Scientists, #Molecular biologists, #Biology, #Molecular Biology, #Science & Technology

Avoid Boring People: Lessons From a Life in Science (3 page)

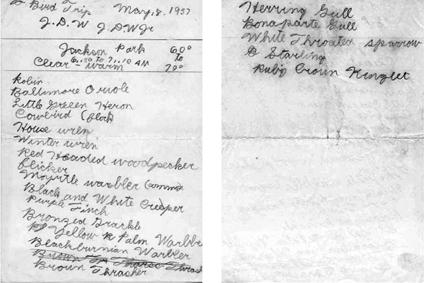

Early on I learned from my father to keep careful notes on birds.

My mother, by then a captain of our Seventh Ward precinct, enjoyed working for the Democratic Party. Our basement became the local polling station, earning us ten dollars per election, and my mother made another ten manning the polls. At the 1940 Democratic National Convention, held in Chicago, we rooted, to no avail, for Paul McNutt, Indiana's handsome governor then bidding to be chosen as Roosevelt's running mate.

In the evenings, Dad often was consumed with work brought home from the office. His principal task as collection manager of the LaSalle correspondence school was to write letters dunning students for delinquent payments. He never believed in threatening them, instead cajoling them with reminders of how their studies of the law or accounting would help them advance to high-paying jobs. I now realize how difficult it must have been to keep the job, he being a socialist-leaning Democrat sympathetic to the students who couldn't pay. No one, however, could accuse him of not working hard or of undermining free enterprise or, for that matter, of frowning upon the plutocratic game of golf, which he first came to enjoy in youth but later could play only on company outings after the Depression had forced the sale of the family Hudson.

Ten years old and soon to abandon Sunday mass for Sunday morning bird-watching

Our family always rooted for Franklin Roosevelt and his New Deal's promise to rescue the downtrodden from the heartless grasp of unregulated capitalism. We were naturally on the side of the strikers in their violent confrontations with U.S. Steel at the massive South Side mill two miles east of our home along the shore of Lake Michigan. Matters of economics, however, began to concern our family less as the German menace grew. My father was a strong supporter of the English and French, the Allies on whose side he had fought in the First World War. He would have found the Germans a natural enemy even without Hitler.

I remember his anguish when Madrid fell to Franco. The local radio stations played up the defeat of the communist-backed republicans, but Father then saw fascism and Nazism as the real evils. By the time of Munich, the news from Europe was as much cause to be glued to the radio as was the Lone Ranger or the Chicago Cubs. Particularly crucial to us was the outcome of the 1940 presidential election, wherein Roosevelt sought his third term and was opposed by Wendell Willkie. Seemingly almost as awful as the Nazis themselves were America's isolationists, who wanted to stay out of the problems of Europe. My father was among those who saw in Charles Lindbergh's visit to Germany a manifestation of anti-Semitism.

Occasionally my parents had nasty disagreements about misspending what little money they had. But these frustrations were never passed on to my sister and me, and we each regularly received five cents for the Saturday afternoon double features at the nearby Avalon Theatre. Our parents would join us for some movies, one such occasion being John Ford's adaptation of Steinbeck's epic chronicle

The Grapes of Wrath.

The message that great decency by itself does not generate a happy ending never left me. A long drought that turned fertile farmlands into dust clouds should not cause a family to lose everything. How any responsible citizen could see this film and not see the good brought about by the New Deal boggled my imagination.

I always liked going to grammar school and twice skipped a half grade, graduating when I was just thirteen. Somewhat downcasting were the results of my two IQ tests, discovered by stealthy looks at teachers’ desktops. In neither test did I rise much above 120.1 got more encouragement from my reading comprehension scores, which placed me at the top of my class. I graduated from grammar school in June 1941, just after Germany invaded Russia. By then Churchill had joined Roosevelt as a hero of mine, and on most evenings we listened to Edward R. Murrow reporting from London on the CBS news. That summer was broken by my first time away from my family, going by train for two weeks in August to Owasippe Scout Reservation in Michigan above Muskegon on the White River. There I enjoyed working for nature-oriented merit badges that made me a Life Scout. Less fun were the overnight camping trips, in which I would invariably lag behind the other hikers, catching up only when they stopped to rest. Nonetheless, I came home content to have spotted thirty-seven different bird species.

Russell Hart (center) and I on the way to Boy Scout camp in 1941

I could not help realizing, however, that as a boy expert on birds I was far behind the much younger Gerard Darrow, who thanks to a prodigious memory became a Chicago celebrity when as a four-year-old ornithologist his story and talent were written up in the

Chicago Daily News.

I would resent him even more when he became the first famous “Quiz Kid” of a Sunday afternoon radio program that first aired in June 1940. Groups of five children, each of whom received a $100 defense bond, were asked questions by the host, the third-grade-educated Jolly Joe Kelley Previously he had been emcee of the

National Barn Dance,

having first come to radio fame by reading the funnies on WLS. Almost instantaneously,

Quiz Kids

became a national sensation, with its weekly listenership between ten million and twenty million—almost half the giant audiences that listened to Jack Benny, Bob Hope, and Red Skelton.

Virtually every Sunday afternoon for over two years, I listened to

Quiz Kids

hoping that somehow I might get on the program and win a war bond. Stoking this hope was the fact that one of the show's producers, Ed Simmons, lived in the apartment house next to our bungalow. Finally, because of a successful audition or because of Ed Simmons's influence, I became a fourteen-year-old Quiz Kid in the fall of 1942. My first two appearances went well, with lots of questions suited to my expertise. But my third time on, I was up against an eight-year-old called Ruth Duskin and a battery of questions on the Bible and Shakespeare dominating the thirty-minute horror. I had never been encouraged to know the plots of Shakespeare, and my early Catholic upbringing had furthermore shielded me from any knowledge of the Old Testament. So it was virtually preordained that I would not be one of the three contestants to come back for the next program. When we went home I bitterly felt the want of encyclopedic knowledge and quick wits needed for semipermanence as a Quiz Kid. But I was nevertheless three defense bonds richer. Later these were used to purchase a pair of 7×50 Bausch and Lomb binoculars to replace the ancient pair my father had used as a birder in his youth.

As a Quiz Kid in 1942, second from the left, doomed by my lack of familiarity with the Bible and Shakespeare

By then I was a sophomore at the newly built South Shore High School. I continued as a largely S (superior) student, though I encountered much more competition than I had at Horace Mann. There was a great Latin teacher, Miss Kinney, who sent me off to the state Latin exams with the more stellar student Marilyn Weintraub, on whom I had a slight crush that no one ever knew about. I was then acutely conscious of my size, only five feet tall when entering high school, and shorter than my sister, who went through puberty early and reached her final height of five feet three inches while I was still only five foot one.

Dad and I spotted the seldom-seen white-winged scoter off Jackson Park in Lake Michigan.

I worked on and off behind a neighborhood drugstore soda fountain making Cokes from syrup and carbonated water. The other conventional teenage job possibility was as a bicycle newspaper delivery boy. But that would have prevented my going on early bird walks with my father and was never seriously considered. Particularly in May, we would routinely get up while it was still dark so we could arrive in Jackson Park soon after sunrise. That way we would have almost two hours to go after the rarer warblers, principally in the region of Wooded Island. Dad's ear for birdsongs was much better than mine— upon hearing, say, the rough sound of the scarlet tanager, he never mistook it for the more melodious Baltimore oriole, which also migrates into Chicago just after the leaves come out. Afterward, Dad would catch a northbound streetcar to his work, while I would get a trolley going in the opposite direction, which would let me off near school.

It was in Jackson Park in 1919 that Dad had met the extraordinarily talented but socially awkward sixteen-year-old University of Chicago student Nathan Leopold, who was equally obsessive about spotting rare birds. In June 1923, Leopold's wealthy father financed a birding expedition so Nathan and my dad could go to the jack pine barrens above Flint, Michigan, in search of the Kirkland warbler. In their pursuit of this rarest of all warblers, they were accompanied by their fellow Chicago ornithologists George Porter Lewis and Sidney Stein, as well as by Nathan's boyhood friend Richard Loeb, whose family helped form the growing Sears, Roebuck store empire.

I had just entered high school when Dad and Mother first told me of Nathan and how for a thrill he and Richard Loeb had brutally killed a younger acquaintance, Bobby Franks. After offering Bobby a ride home from school, they fatally struck him in the head, disposing of the body in a culvert adjacent to the Eggers Wood birding site to which Dad later often brought me. Some six months before Nathan's senseless though nearly perfect crime of May 24,1924, his father contacted mine expressing worry about his son's obsessive fascination with Loeb. Nathan by then was already at the University of Chicago Law School and Dad had no acquaintance with the rich college youths that Leopold and Loeb moved among. In July, Leopold and Loeb were defended in a Chicago courtroom filled with newspapermen by the celebrated Clarence Darrow, who asked Dad to appear as a character witness. But his family advised against this action, saying it would mark him for life in Chicago.