AWOL on the Appalachian Trail (33 page)

Read AWOL on the Appalachian Trail Online

Authors: David Miller

After our nineteen miles of hiking are complete, we still have a half-mile side trail to walk before reaching the lean-to. We arrive as the sky begins to darken. The sun sets about six minutes sooner each day as the season transitions from summer to fall. At 7:20 p.m. it is dark. Cloud Pond Lean-to is yet another in Maine that is paired with a pond.

The moon is illuminating the shelter when I wake up near midnight. Kiwi has a headlamp on and is watching the mice. His pack is hung about a foot from his food bag. The mice drop from the rafters onto the pack and leap from the pack over to the food.

In the morning, Kiwi finds that he has suffered only minor loss of food to the mice. Overnight the temperature fell into the thirties, making for a chilly morning, but shortly into my hiking day I am able to pare down to my shorts and T-shirt. It is excellent hiking weather, and I rarely break a sweat. Hiking in the 100-Mile Wilderness is easier than the hiking in southern Maine, but it is no cakewalk. Short but precipitous ascents and descents continue. I pause when the downhill trail leads into what looks like a rockslide, similar to the rockslide we ascended at the end of the day yesterday. Climbing down will be much more treacherous. The bike accident comes to mind, causing me to think how vulnerable people are and how unfortunate it would be to get hurt here, so close to the end of my hike.

I'm frustrated with the trail at the moment. There seems to be no reason for it to be so precarious. I wish the AT would wind down the mountainside on switchbacks. I'm taking this obstacle personally, as if it was put here with the intent to trip me up. I'd like to hurl every expletive I know at the trail at this moment. Kiwi comes up behind me and says, in his genteel New Zealand accent, "It's quite steep here, isn't it?" His statement is so understated it makes me laugh. After working our way down the mountain, I stop to take a long break and regroup. I encourage Kiwi to continue on, and I spend time writing.

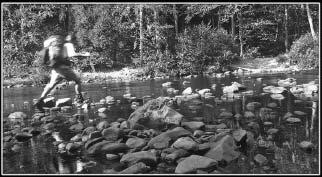

Late in the afternoon I reach the Pleasant River. It is the widest river since the Kennebec, and there is no ferry. It is twenty-five yards across, but studded with enough rock to give me hope of crossing without getting wet. I progress stepping from rock to rock, easily at first, then having to make longer jumps. I come to an impasse tantalizingly close to the far shore. I backtrack and then try to advance picking rocks a bit more upriver. Again, I am thwarted just fifteen feet from the north shore.

I return all the way to the shore where I started, change into my rubber clog camp shoes, and begin to wade across. The water is numbingly cold, and my ankles immediately start to ache with the curious pain induced by cold. The clear water in the deepest part of the river is deeper than I expected. It is up to my knees and is threatening the hem of my shorts. I'd like to hurry across, but the push of the water is surprisingly strong. I try to spear my trekking poles into the river bed for support, but the current slaps them away as soon as they touch the surface. The power of the river nearly dislodges one of my clogs. I wiggle my foot back into place and shuffle the rest of the way across the river.

Awol rock-hopping the Pleasant River.

On the north bank, I quickly put socks and shoes on my wet, blue feet. Beyond the Pleasant River the trail is smooth and takes a gradual upslope. I walk alone in the quiet woods and ponder the difficulties of my day. I think myself unfit for this hike, being so susceptible to cold and being discombobulated by the rockslide descent earlier. I want to give myself no credit for hiking two thousand miles; I am just the beneficiary of favorable conditions. The "cold" weather, as I perceive it now, is mild for Maine at this time of year, and I have been fortunate to have little rain to deal with since leaving Vermont.

My arrival makes for a full house at the Carl Newhall Lean-to. Kiwi is here, along with some weekend hikers, and I am surprised and pleased to see Biscuit once again. Her boyfriend, whom she has dubbed Grasshopper, has joined her for a week of hiking. A huge campfire is raging in front of the shelter, and the weekend hikers are throwing all of their trash, flammable or not, into the fire.

In the morning I wake to see Biscuit picking shriveled lumps of plastic and foil from the pit. Kiwi has already left, and Biscuit and Grasshopper leave before I am packed. The lean-to is located partway up the south face of White Cap Mountain. Immediately leaving the shelter, the AT steeply resumes the ascent of the mountain. It is a rocky and challenging walk, and I catch up with Grasshopper and Biscuit sooner than I expect. Grasshopper is standing with his hands on his hips, panting for breath. Biscuit is ahead of him, looking back over her shoulder, as if waiting for him to continue hiking. They are not talking, and neither says anything as I pass. I assume they my have been arguing, or that Biscuit was impatient with having to go at a slower pace. It would be difficult for any visitor to keep up with a thru-hiker at this stage.

I am moving a bit faster today, eager to get my first look at Mount Katahdin. My anticipation builds as I can see the trail peaking the crest ahead. At the top, I am disappointed to find that it is a secondary summit. The trail descends again before heading up the major summit of White Cap Mountain. Near the top, the incline of the trail lessens and bends to my right to make a more gradual, teasing approach to the top. I am not sure if my bearing is east or north, or if Katahdin is east, west, or north of White Cap. About the only place I know I can rule out spotting Katahdin is directly behind me. I am above timberline, scanning everywhere I can see and craning my head to peer over the shoulder of the mountain that I am on at this moment. My pace has quickened, as if Katahdin might sneak away if I don't rush to get a glimpse. I see some distant peaks, and I give each a good look, not knowing how "the Big K" will appear from this distance. Nothing stands out. I reach the peak of White Cap and see that the trail curves left and descends on a gradual side-hill course. I now have a clear view to my left, and there it is! Mount Katahdin stands out as a bulking, unambiguous monolith even when viewed seventy-two trail miles from its summit.

Content already with my day, I ease down to Logan Brook Lean-to on the north face of White Cap and take a lengthy lunch break. From there, I meander down to East Branch Lean-to, where I catch up with Kiwi once again. We are relaxed, put at ease by the sight of Katahdin. We really have made it. There are minor hills to climb, but they get progressively lower, diminishing like attenuating waves--the last ripples of the mountain range.

Kiwi and I are feeling hunger after three long days, and we talk about the food we enjoy "back home." Fish and chips is the most popular meal in New Zealand. I crave volume--all-you-can-eat-buffet food cooked three hours ago in five-gallon trays and warmed by heat lamps. I want to go to a place that has a dessert bar where patrons cut their own servings from a slab of cake, and I can come along and scoop up all the crumbs and oodles of leftover icing.

We stop at Cooper Brook Falls Lean-to. Cooper Brook Falls cascades into a wide pool of water in front of the shelter. A section hiker named David is also staying in the lean-to. He will be ending his hike sooner than planned and gives me a day's worth of food. I cook freeze-dried spaghetti.

Biscuit and Grasshopper come in around midnight, walking under the light of the full moon. Biscuit is quick to apologize for their reticence earlier in the day. It is September 11, and they had decided to observe the day with silence.

I cannot get back to sleep. I recall events of my thru-hike. I think about the conclusion of the trip, what it might feel like to finish, and what I'll do when I get back home. I dismiss some of the anxiety I had in Gorham over the lack of change effected by my trip. The radical break from routine that I made in coming on this adventure unloaded the attic of my mind. Everything that I had stored away, out of habit, I've taken out and reexamined. I've yet to rearrange, toss things out, and repack. But most important, I should not treat this journey simply as an agent for change. It is an experience in and of itself. I am unequivocally pleased doing this.

I am the first to leave in the morning. Less than a mile from the lean-to I see a mother bear with two nearly grown cubs. One cub climbs a tree, but he sems too heavy to get very high or hang on for long. Realizing the tactic is doing him little good, he jumps down and runs away.

The trail is level and smooth, and I speed along, all the way to Antlers Campsite. I read the guidebook mileage and I'm able to determine that my pace is nearly four miles per hour. Just beyond the campsite, I find a rock the size of a bench and sit for a break. The forest looks ancient. Bark on the trees has accumulated moss and has deep fissures, akin to the age-spotting and wrinkling of aged humans. The added texture gives the trees character with no loss of vitality. They look like survivors, resilient and deeply rooted.

I dawdle, waiting for Kiwi. Now I am the one who enjoys having a hiking partner. I plan to end my day at a hostel called Whitehouse Landing. When I last spoke with Kiwi, he had not yet decided if he would stop there. Kiwi arrives, and we hike together to Pemadumcook Lake, where we get our second look at Mount Katahdin. The lake is shallow near this shore; large boulders protrude from the lake, far out into the water. Above the water, there is a band of dark green--the trees on the far shore--and then there is the ghostly lump of Katahdin, the only land visible above the trees. The color of the mountain is dulled by distance, but the timberline is distinct. The rocks atop the mountain give it the appearance of being capped by snow.

Two miles later, we reach the mile-long side trail to the hostel. Kiwi has decided to come along. At the end of the trail, we reach a boat dock on the extensive shoreline of Pemadumcook Lake, the same lake from which we had the earlier view of Katahdin. Whitehouse Landing is on the other side of the lake. There is an air horn on the boat dock; we give it a blast and Bill, the owner of the hostel, comes to ferry us across in a motorboat. Whitehouse Landing is a complex with multiple cabins alongside the bunkroom where we stay. The modest main building serves as the office, lodge, camp store, and dining area. A lazy hound dog is a fixture on the porch. Kiwi and I are the only guests tonight. Bill tells us that his place is also an ice fishing outpost in the winter. There is no electricity or public phone, but there are propane-heated showers and battery-powered lights.

Bill cooks us one-pound hamburgers for dinner. "Would you like cheese on that?"

"Of course." The hamburger is a mess to eat, but it is delicious. For dessert, I have a New England whoopie pie. It is made with two bun-shaped pieces of chocolate cake and creamy frosting sandwiched between. It is as large as the hamburger.

At sunset Kiwi and I take the canoe out on the lake. We row far enough out on the choppy lake to get another view of Katahdin's peak. The sky on the western horizon is pink with the last traces of sun, and it transitions upward through shades of mauve, purple, and blue. Directly overhead, the sky is deep blue; panning down to the east, the hue darkens and stars are already visible. Darkness comes early and fast, too hurried, like a drawn curtain. My hike is nearly over.

In the morning, Bill gives Kiwi and me a boat ride back to the trail, and we hike on together. The AT takes a crab-wise route to Katahdin, winding around lakes and ponds, which gives us views of the mountain from different angles. Nesuntabunt Mountain is the only climb of the day. It is an unusually twisting, disorienting climb. We stop for lunch on top, where we have a "side" view of Katahdin. The postcard view of Katahdin, which I arbitrarily deem to be the "front," shows the mountain broadside, with a barely discernible center summit and symmetrical summits on the shouders that are nearly as high. From Nesuntabunt, Katahdin looks narrower and taller.

When we return to the trail, I am in front.

"Where are you going?" Kiwi asks.

"This is the trail, isn't it?" I answer.

"Yes, but you are going back the way we came."

"Are you sure?"

"Quite sure."

I feel certain about my choice, but there really is no way to be sure. Both paths seem to lead away from Katahdin. Since we are at the top of a mountain, both ways go downhill. I reluctantly follow Kiwi's direction since he seems more certain than I am. It takes me more than a quarter of a mile to be convinced of our direction, but he is right.

After descending Nesuntabunt, the trail levels and runs parallel to a gorge. A wide stream flows in the center of the gorge ten to thirty feet below us as the land undulates and the stream maintains its gradual downhill course. The coming of fall is increasingly evident; we crunch through fallen leaves, and the maple trees, still holding on to their red and yellow leaves, stand out like torches. Along with Kiwi, Ken, and Marcia, I set up my tarp next to Rainbow Lake. Loons on the lake make calls that sound as if they are blown from a flute. This will be my last night on the trail.

Way back in Hiawassee, I had cut eighty-five pages of mileage data loose from my guidebook. I keep the most current page in a Ziploc bag and tuck it in my pants pocket. I start the day by paring down to the last sheet. My goal is to get to the base of Katahdin and then hitch out to the town of Millinocket, where I'll wait for my family before hiking the final five miles of trail.