B0041VYHGW EBOK (109 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

6.133

Mon Oncle d’Amérique.

6.134

Mon Oncle d’Amérique.

More drastically, a filmmaker may violate or ignore the 180° system. The editing choices of filmmakers Jacques Tati and Yasujiro Ozu are based on what we might call 360° space. Instead of an axis of action that dictates that the camera be placed within an imaginary semicircle, these filmmakers work as if the action were not a line but a point at the center of a circle and as if the camera could be placed at any point on the circumference. In

Mr. Hulot’s Holiday, Play Time,

and

Traffic,

Tati systematically films from almost every side; edited together, the shots present multiple spatial perspectives on a single event. Similarly, Ozu’s scenes construct a 360° space that produces what the continuity style would consider grave editing errors. Ozu’s films often do not yield consistent relative positions and screen directions; the eyeline matches are out of joint, and the only consistency is the

violation

of the 180° line. One of the gravest sins in the classical continuity style is to match on action while breaking the line, yet Ozu does this comfortably in

Early Summer

(

6.135

,

6.136

).

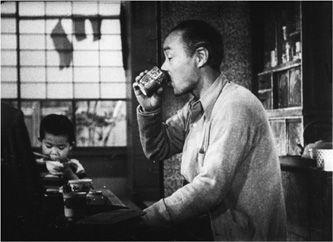

6.135 In

Early Summer,

Ozu cuts on the grandfather’s gesture of drinking …

6.136 … directly to the opposite side of the characters.

Such spatially discontinuous cutting affects the spectator’s experience as well. The defender of classical editing would claim that spatial continuity rules are necessary for the clear presentation of a narrative. But anyone who has seen a film by Ozu or Tati can testify that no narrative confusion arises from their continuity violations. Though the spaces do not flow as smoothly as in the Hollywood style (this is indeed part of the films’ fascination), the causal developments remain intelligible. The likeliest conclusion is that the continuity system is only

one

way to tell a story. Historically, this system has been the dominant one, but artistically, it isn’t a necessity.

There are two other notable devices of discontinuity. In

Breathless,

Jean-Luc Godard violates conventions of spatial, temporal, and graphic continuity by his systematic use of the

jump cut

. Though this term is often loosely used, its primary meaning is this: when two shots of the same subject are cut together but are not sufficiently different in camera distance and angle, there will be a noticeable jump on the screen. Classical continuity avoids such jumps by generous use of shot/reverse shots and by the

30° rule

(advising that every camera position be varied by at least 30° from the previous one). An examination of shots from

Breathless

suggests the consequences of Godard’s jump cuts

(

6.137

,

6.138

).

Far from flowing unnoticeably, such cuts are very visible.

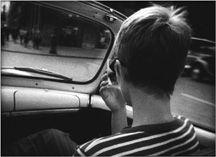

6.137 In

Breathless,

in the jump cut from this shot of Patricia …

6.138 … to this one, the background has changed and some story time has gone by.

Jump cuts should not be confused with those elliptical cuts that convey the passage of time by showing a person in different positions. We saw an instance earlier (

6.121

–

6.123

) in which Wendy is sitting in two positions on her cell bunk. In cuts like this one, we have two distinct angles on the subject, in accordance with the 30° rule. The jump cut shows the action from a single angle.

Today’s mainstream films have somewhat domesticated the jump cut. It can now be found in montage sequences and during moments of surprise or violence. Ridley Scott’s

Matchstick Men

is one film that exploits the technique as extensively as

Breathless

does.

A second violation of continuity is created by the

nondiegetic insert

. Here the filmmaker cuts from the scene to a metaphorical or symbolic shot that is not part of the space and time of the narrative. Clichés abound here

(

6.139

,

6.140

).

More complex examples occur in the films of Eisenstein and Godard. In Eisenstein’s

Strike,

the massacre of workers is intercut with the slaughter of a bull. In Godard’s

La Chinoise,

Henri tells an anecdote about the ancient Egyptians, who, he claims, thought that “their language was the language of the gods.” As he says this

(

6.141

),

Godard cuts in two close-ups of relics from the tomb of King Tutankhamen

(

6.142

,

6.143

).

As non diegetic inserts, coming from outside the story world, these shots construct a running, often ironic, commentary on the action, and they prompt the spectator to search for implicit meanings. Do the relics corroborate or challenge what Henri says?

6.139 In

Fury,

Lang cuts from housewives gossiping …

6.140 … to shots of clucking hens.

6.141 A diegetic shot in

La Chinoise

is followed by …