B0041VYHGW EBOK (148 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Now the problem has been introduced and discussed, and emotional appeals have prepared the audience to accept a solution. Segment 8 presents that solution and begins the part of the film devoted to the proofs that this solution is an effective one. In segment 8, the map of the opening titles returns, and the narrator says, “There is no such thing as an ideal river in nature, but the Mississippi River is out of joint.” Here we have another example of an enthymeme—an inference assumed to be logically valid and factually accurate. The Mississippi may be “out of joint” for certain uses, but would it present a problem to the animals and plants in its ecosystem? This statement assumes that an “ideal” river would be one perfectly suited to

our

needs and purposes. The narrator goes on to give the film’s most clear-cut statement of its argument: “The old River

can

be controlled. We had the power to take the Valley apart. We have the power to put it together again.”

Now we can see why the film’s form has been organized as it has. In early segments, especially 3 and 5, we saw how America developed great agricultural and industrial strength. At the time, we might have taken these events as simple facts of history. But now they turn out to be crucial to the film’s argument. That argument might be summarized this way: We have seen that the American people have the power to build and to destroy; therefore, they have the power to build again.

The narrator continues, “In 1933 we started …,” going on to describe how Congress formed the TVA. This segment presents the TVA as an already settled solution to the problem and offers no other possible solutions. Thus something that was actually controversial seems to be a matter of straightforward implementation. Here is a case where one solution, because it has so far been effective in dealing with a problem, is taken to be

the

solution. Yet, in retrospect, it is not certain that the massive series of dams built by the TVA was the single best solution to flooding. Perhaps a less radical plan combining reforesting with conservation-oriented farming would have created fewer new problems (such as the displacement of people from the land flooded by the dams). Perhaps local governments rather than the federal government would have been more efficient problem solvers.

The River

does not bother to rebut these alternatives, relying instead on our habitual inference from problem to solution.

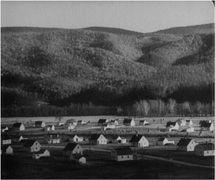

Segment 9 contains similarities to and differences from several earlier parts. It begins with a list of dams, which we see in progress or finished. This echoes the lists of rivers, trees, towns, and so on that we have heard at intervals. The serene shots of the artificial lakes that follow link the ending to the beginning, recalling the lyrical river shots of

segment 2

(

10.40

).

The displaced, flooded-out, and unemployed people from segment 6 seem now to be happily at work, building planned model towns on government loans. Electricity generated by the dams links these rural communities to those “hundred cities and thousand towns” we heard about earlier, bringing to the countryside “the advantages of urban life.” Many motifs planted in a simple fashion are now picked up and woven together to act as proofs of the TVA’s benefits. The ending shows life as being parallel to the way it was in the beginning—beautiful nature, productive people—but enhanced by modern government planning. The film’s middle segments have denied us the picturesque views of mountains and sky we saw at the beginning. But after the introduction of the TVA, such shots return

(

10.41

–

10.43

).

Tying the ending back to the beginning, the imagery shows a return to idyllic nature, under the auspices of government planning.

10.40 A beautiful lake in

The River.

10.41 In

The River,

men going to work are framed in low angle against the sky.

10.42 Soon after this, one shot begins on a hillside, also against the sky, then tilts down …

10.43 … to reveal the model town.

An upswell of music and a series of images of the dams and rushing water create a brief epilogue summarizing the factors that have brought about the change—the TVA dams. Under the ending titles and credits, we see the map again. A list tells us the names of the various government agencies that sponsored the film or assisted in its making. These again seem to lend authority to the source of the arguments in the film.

The River

achieved its purpose. Favorable initial response led a major American studio, Paramount, to agree to distribute the film, a rare opportunity for a government-sponsored short documentary at that time. Reviewers and public alike greeted the film enthusiastically. A contemporary critic’s review testifies to the power of the film’s rhetorical form. After describing the early portions, Gilbert Seldes wrote, “And so, without your knowing it, you arrive at the Tennessee Valley—and if this is propaganda, make the most of it, because it is masterly. It is as if the pictures which Mr. Lorentz took arranged themselves in such an order that they supplied their own argument, not as if an argument conceived in advance dictated the order of the pictures.”

President Roosevelt himself saw

The River

and liked it. He helped get congressional support to start a separate government agency, the U.S. Film Service, to make other documentaries like it. But not everyone was in favor of Roosevelt’s policies or believed that the government should set itself up to make films that essentially espoused the views of the administration currently in office. By 1940, the Congress had taken away the U.S. Film Service’s funding, and documentary films were once again made only within the separate sections of the government. In such ways, rhetorical form can lead both to direct action and to controversy.

Another basic type of filmmaking is willfully nonconformist. In opposition to dominant, or mainstream, cinema, some filmmakers set out to create films that challenge orthodox notions of what a movie can show and how it can show it. These filmmakers work independently of the studio system, and often they work alone. Their films are hard to classify, but usually they are called

experimental

or

avant-garde.

Experimental films are made for many reasons. The filmmaker may wish to express personal experiences or viewpoints in ways that would seem eccentric in a mainstream context. In

Mass for the Dakota Sioux,

Bruce Baillie suggests a despair at the failure of America’s optimistic vision of history. Su Friedrich’s

Damned If You Don’t,

a story of a nun who discovers her sexuality, presents the theme of release from religious commitment. Alternatively, the filmmaker may seek to convey a mood or a physical quality

(

10.44

,

10.45

).

10.44 Maya Deren’s

Choreography for Camera

frames and cuts a dancer’s movements …

10.45 … to suggest graceful passage across different times and places.

The filmmaker may also wish to explore some possibilities of the medium itself. Experimental filmmakers have tinkered with cinema in myriad ways. They have presented cosmic allegories, such as Stan Brakhage’s

Dog Star Man,

and highly private japes, as in Ken Jacobs’s

Little Stabs at Happiness.

Robert Breer’s

Fist Fight

experiments with shots only one or two frames long (

6.127

); by contrast, the shots in Andy Warhol’s

Eat

last until the camera runs out of film. An experimental film might be improvised or built according to mathematical plan. For

Eiga-zuke (Pickled Film),

Japanese American Sean Morijiro Sunada O’Gara applied pickling agents to negative film and then handprinted the blotchy abstractions onto positive stock.