B0041VYHGW EBOK (185 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Early cinema was influenced by other media of its day, including narrative painting. We suggest some similarities in “Professor sees more parallels between things, other things.”

In 1882, another scientist interested in analyzing animal movement, the Frenchman Étienne-Jules Marey, invented a camera that recorded 12 separate images on the edge of a revolving disc of film on glass. This constituted a step toward the motion picture camera. In 1888, Marey built the first camera to use a strip of flexible film, this time on paper. Again, the purpose was only to break down movement into a series of stills, and the movements photographed lasted a second or less.

In 1889, George Eastman introduced a crude flexible film base, celluloid. Once this base was improved and camera mechanisms had been devised to draw the film past the lens and expose it to light, the creation of long strips of frames became possible.

Projectors had existed for many years and had been used to show slides and other shadow entertainments. These magic lanterns were modified by the addition of shutters, cranks, and other devices to become early motion picture projectors.

One final device was needed if films were to be projected. Since the film stops briefly while the light shines through each individual frame, there had to be a mechanism to create an

intermittent

motion of the film. Marey used a Maltese cross gear on his 1888 camera, and this became a standard part of early cameras and projectors.

A flexible and transparent film base, a fast exposure time, a mechanism to pull the film through the camera, an intermittent device to stop the film, and a shutter to block off light—all these innovations had been achieved by the early 1890s. After several years, inventors working independently in many countries had developed different film cameras and projection devices. The two most important firms were the Edison Manufacturing Company in America, owned by inventor Thomas A. Edison, and Lumière Frères in France, the family firm of Louis and Auguste Lumière.

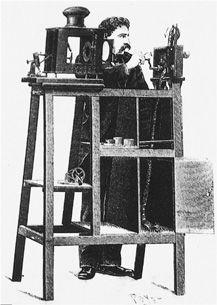

By 1893, Thomas A. Edison’s assistant, W.K.L. Dickson, had developed a camera that made short 35mm films. Interested in exploiting these films as a novelty, Edison hoped to combine them with his phonograph to show sound movies. He had Dickson develop a peep-show machine, the

Kinetoscope

(

12.1

),

to display these films to individual viewers.

12.1 The Kinetoscope held film in a continuous loop threaded around a series of bobbins.

Since Edison believed that movies were a passing fad, he did not develop a system to project films onto a screen. This task was left to the Lumière brothers. They invented their own camera independently; it exposed a short roll of 35mm film and also served as a projector

(

12.2

).

On December 28, 1895, the Lumière brothers held one of the first public showings of motion pictures projected on a screen, at the Grand Café in Paris.

12.2 Placing a magic lantern behind the Lumière camera turned it into a projector.

There had been several earlier public screenings, including one on November 1 of the same year by the German inventor Max Skladanowsky. But Skladanowsky’s bulky machine required two strips of wide-gauge film running simultaneously and hence had less influence on the subsequent technological development of the cinema. Although the Lumières didn’t wholly invent cinema, they largely determined the specific form the new medium was to take. Edison himself was soon to abandon Kinetoscopes and form his own production company to make films for theaters.

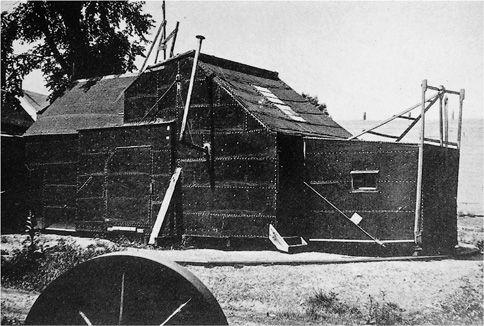

The first films were simple in form and style. They usually consisted of a single shot framing an action, usually at long-shot distance. In the first film studio, Edison’s Black Maria

(

12.3

),

vaudeville entertainers, famous sports figures, and celebrities like Annie Oakley performed for the camera. A hinged portion of the roof opened to admit a patch of sunlight, and the entire building turned on a circular rail (visible in

12.3

) to follow the sun’s motion. The Lumières, however, took their cameras out to parks, gardens, beaches, and other public places to film everyday activities or news events, as in their

Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat

(

5.61

).

12.3 The hinged portion of the Black Maria’s roof, at the center, swung open for filming.

Until about 1903, most films showed scenic places or noteworthy events, but narrative form also entered the cinema from the beginning. Edison staged comic scenes, such as one copyrighted 1893 in which a drunken man struggles briefly with a policeman. The Lumières made a popular short

L’Arroseur arrosé

(

The Waterer Watered,

1895), also a comic scene, in which a boy tricks a gardener into squirting himself with a hose (

4.8

).

After the initial success of the new medium, filmmakers had to find more complex or interesting formal properties to keep the public’s interest. The Lumières sent camera operators all over the world to show films and to photograph important events and exotic locales. But after making a huge number of films in their first few years, the Lumières reduced their output, and they ceased filmmaking altogether in 1905.

“In conjuring you work under the attentive gaze of the public, who never fail to spot a suspicious movement. You are alone, their eyes never leave you. Failure would not be tolerated. … While in the cinema … you can do your confecting quietly, far from those profane gazes, and you can do things thirty-six times if necessary until they are right. This allows you to travel further in the domain of the marvellous.”

— George Méliès, magician and filmmaker

In 1896, Georges Méliès purchased a projector from the British inventor Robert William Paul and soon built a camera based on the same mechanism. Méliès’s first films resembled the Lumières’ shots of everyday activities. But as we have seen (

pp. 113

–

115

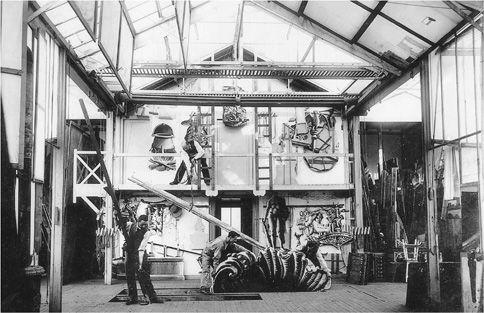

), Méliès was also a magician, and he discovered the possibilities of simple special effects. In 1897, Méliès built his own studio. Unlike Edison’s Black Maria, Méliès’s studio was glass-sided like a greenhouse, so that the studio did not have to move with the sun

(

12.4

).

12.4 Méliès’s glass-sided studio admitted sunlight from a variety of directions.

Méliès also began to build elaborate settings to create fantasy worlds within which his magical transformations could occur. We have already seen how Méliès thereby became the first master of mise-en-scene technique (

4.3

–

4.6

). From the simple filming of a magician performing a trick or two in a traditional stage setting, Méliès progressed to longer narratives with a series of tableaux. Each consisted of one shot, except when the transformations occurred. These were created by cuts designed to be imperceptible on the screen. He also adapted old stories, such as

Cinderella

(1899), or wrote his own. All these factors made Méliès’s films extremely popular and widely imitated.

During this early period, films circulated freely from country to country. The French phonograph company Pathé Frères moved into filmmaking from 1901 on, establishing production and distribution branches in many countries. Soon Pathé was the largest film concern in the world, a position it retained until 1914, when the beginning of World War I forced it to cut back production. In England, several entrepreneurs managed to invent or obtain their own filmmaking equipment and made scenics, narratives, and trick films from 1895 into the early years of the 20th century. Members of the Brighton School (primarily G. Albert Smith and James Williamson), as well as others like Cecil Hepworth, shot their films on location or in simple open-air studios (as in

12.5

). Their innovative films circulated abroad and influenced other filmmakers. Pioneers in other countries invented or bought equipment and were soon making their own films of everyday scenes or fantasy transformations.

12.5 G. Albert Smith’s

Santa Claus

(1898).

From about 1904 on, narrative form became the most prominent type of filmmaking in the commercial industry, and the worldwide popularity of cinema continued to grow. French, Italian, and American films dominated world markets. Later, World War I was to restrict the free flow of films from country to country, and Hollywood emerged as the dominant industrial force in world film production, contributing to the creation of distinct differences in the formal traits of individual national cinemas.