B0041VYHGW EBOK (181 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

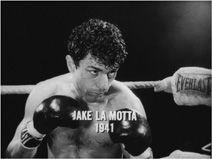

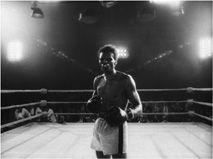

11.105 Realistic violence in the boxing scenes.

He creates a realistic social and historical context by using other conventions. One of these is a series of superimposed titles that identify each boxing match by date, locale, and participants. This narrational ploy yields a quasi-documentary quality.

The most important factor creating realism, however, is probably the acting. Aside from Robert De Niro, the cast was chosen from virtually unknown actors or nonactors. As a result, they did not bring glamorous star associations to the film. De Niro was known mainly for his grittily realistic performances in Scorsese’s

Mean Streets

and

Taxi Driver,

as well as Michael Cimino’s

The Deer Hunter.

In

Raging Bull,

the actors speak with thick Bronx accents, repeat or mumble many of their lines, and make no attempt to create likable characters. In the publicity surrounding the film, much was also made of the fact that De Niro gained 60 pounds in order to play Jake as an older man. The film emphasizes De Niro’s transformation by cutting straight from a medium close-up of Jake at the end of

segment 2

, in 1964

(

11.106

),

to a similar framing of him in the ring in 1941

(

11.107

).

Such realism in the acting and other techniques makes it difficult for us to accept the film’s violence casually, as we might in a conventional horror or crime film.

11.106 A graphic match moves the film from the end of the 1964 opening …

11.107 … to Jake in 1941.

Through its narrative structure and its use of the stylistic conventions of realism, the film thus offers a criticism of violence in American life, both in the ring and in the home. Yet the film doesn’t permit us to condemn Jake as merely a raging bull. It also presents violence as fascinating and ambiguous. Although the fight scenes favor brutal realism, aspects of them are distorted in mesmerizing ways. The sounds of punches assault our ears with shuddering impact. The sound mix for the fights blended animal cries, airplane motors, whizzing arrows, and even music, but the sources are unrecognizable because they are slowed down or played backward.

More broadly, violence is made disturbingly attractive even in the scenes outside the ring because the narration concentrates far more on the perpetrators of the violence than on the victims. In particular, the three important female characters—Jake’s first wife, Joey’s wife Lenore, and Vickie—have little to do in the action except take abuse or rail ineffectually against it. We never learn why they are initially attracted to the violent men they marry or why they stay with them so long. At first Vickie seems to admire Jake for his fame and his flashy car, but her willingness to sustain their marriage for so long is not explained. Indeed, her sudden decision to leave him after 11 years has no specific motivation.

Such victims of Jake’s violence serve chiefly to provoke him to respond. One portion of the action focuses on his pummeling of a “pretty” fighter to whom he thinks Vickie is attracted. Another deals with Jake’s violent reaction to his irrational belief that Joey and Vickie have had an affair. It is notable that after this crisis, when Jake beats Joey up, Joey becomes as peripheral a figure as Vickie. We glimpse him briefly watching Jake’s bloody title defeat and then see a short scene of him resisting Jake’s offer of reconciliation. The film thus offers no positive counterweight to Jake’s excesses.

Another indication of the narration’s fascination with Jake’s violence is the descent into subjective presentation. Several scenes show events from his point of view, using slow motion to suggest that we are seeing not just what he sees but how he reacts subjectively to it. This technique becomes especially vivid when Jake sees Vickie with other men and becomes jealous. Similarly, in the final fight with Robinson, Jake’s vision of his opponent is shown via a point-of-view framing. The POV imagery also incorporates a combined track-forward and zoom-out to make the ring seem to stretch far into the distance, while a decrease in the frontal light makes Robinson appear even more menacing

(

11.108

).

Other deviations from realism, such as the thunderous throbbing on the sound track during Jake’s major victory bout, also suggest that we’re entering Jake’s mind.

11.108 Jake’s point of view during a fight.

In part Scorsese justifies the film’s fascination with violence by emphasizing how self-destructive Jake is. However much he hurts other people, he injures himself at least as much. He also quickly regrets having hurt people, as several parallel scenes show. In

segment 3

, Jake has a vicious argument with his first wife in which he threatens to kill her but then immediately says, “Come on, honey, let’s be—let’s be friends. Truce, all right?” Later, after he has beaten Vickie up for her imagined infidelities, he apologizes and persuades her to stay with him. These domestic reconciliations are echoed in the big title fight where he defeats the current champion, Marcel Cerdan, then walks to his opponent’s corner and magnanimously embraces him.

Sympathy for Jake is reinforced by other means.

Raging Bull

suggests that he is strongly masochistic, using his aggression to induce others to inflict pain on him. This notion is emphasized in the love scene in

segment 4

. There he childishly asks Vickie to caress and kiss the wounds from his triumph over Sugar Ray Robinson

(

11.109

).

Soon Jake denies himself sexual gratification by pouring ice water into his shorts. The scene then leads directly into a fight in which Robinson defeats him.

11.109 A close-up links violence and sexuality as Jake asks Vickie to kiss his bruises.

This defeat is paralleled in segment 8, another boxing scene, when Jake simply stands and goads Robinson into beating him to a pulp. The motif of masochism comes to a climax in segment 9, when Jake is thrown into solitary confinement in a Dade County jail. A long, disturbing take has Jake beating his head and fists against the prison wall, as he asserts that he is not an animal and berates himself as stupid.

More implicitly, the film suggests a strain of repressed homosexuality in Jake’s aggressiveness. His embrace of the defeated opponent, Cerdan, in his title fight, as well as his urging of Robinson to attack him in his final bout, suggest such an interpretation. In segment 6, when Jake sits down at a nightclub table and jokes about how pretty his upcoming opponent is, he tauntingly offers him as a sex partner to a mobster he suspects of being in love with Vickie. In segment 8, one scene begins with an erotically suggestive slow-motion shot of seconds’ hands massaging Jake’s torso. In general, there is a hint that Jake’s fascination with boxing and his refusal to deal with his domestic life stem from an unacknowledged homosexual urge. Such an implication goes against the usual ideology of Hollywood, which assumes that a heterosexual romance is the basis for most narratives.

Ultimately, the ideological stance that

Raging Bull

offers is far from being as straightforward as that of

Meet Me in St. Louis.

Instead of displaying an idealized image of American society, the film criticizes one pervasive aspect of that society: its penchant for unthinking violence. Yet it also displays a considerable fascination with that violence and with its main embodiment, Jake.

The film’s ambiguity intensifies at the end. In segment 12, a biblical quotation appears: “So, for the second time, [the Pharisees] summoned the man who had been blind and said: ‘Speak the truth before God. We know this fellow is a sinner.’ ‘Whether or not he is a sinner, I do not know,’ the man replied. ‘All I know is this: once I was blind and now I can see.’”

As this quotation emerges line by line, we are cued to relate it to the protagonist. Has Jake achieved some sort of enlightenment through his experiences? Several factors suggest not. Despite being a poor actor, he continues to perform literary recitals, trying to regain his public (“I’m the boss”). Furthermore, the speech he practices at the end is the famous “I could have been a contender” passage from

On the Waterfront.

In that film, a failed boxer blamed his brother for his lack of a chance to succeed. Is Jake now blaming Joey or someone else for his decline? Or is it possible that he has become aware enough of his faults to ironically recall a film in which the hero also comes to realize his mistakes?

“I was fascinated by the selfdestructive side of Jake La Motta’s character, by his very basic emotions. What could be more basic than making a living by hitting another person on the head until one of you falls or stops? … I put everything I knew and felt into that film, and I thought it would be the end of my career. It was what I call a kamikaze way of making movies: pour everything in, then forget about it and go find another way of life.”

— Martin Scorsese, director