B0041VYHGW EBOK (89 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

5.196 The zoom-ins in

Wavelength

will soon eliminate the body on the floor from the frame.

From the standpoint of the viewer’s experience,

Wavelength

’s use of frame mobility arouses, delays, and gratifies unusual expectations. What plot there is briefly arouses curiosity (What are the people up to? What has led to the man’s death, if he does die?) and surprise (the apparent murder). But in general, a story-centered suspense is replaced by a

stylistic

suspense: What will the zoom eventually frame? From this standpoint, the colored tints and even the plot work with the spasmodic qualities of the zoom to delay the forward progress of the framing. When the zoom finally reveals its target, our stylistic anticipations have come to fulfillment. The film’s title stands revealed as a multiple pun, referring not only to the steadily rising pitch of the sound track but also to the distance that the zoom had to cross in order to reveal the photo—a “wave length.”

Grand Illusion

and

Wavelength

illustrate, in different ways, how frame mobility can guide and shape our perception of a film’s space and time. Frame mobility may be motivated by larger formal purposes, as in Renoir’s film, or it may itself become the principal formal concern, motivating other systems, as in Snow’s film. By examining how filmmakers use the mobile frame within specific contexts, we can gain a fuller understanding of how our experience of a film is created.

In our consideration of the film image, we have emphasized spatial qualities—how photographic transformations can alter the properties of the image, how framing defines the image for our attention. But cinema is an art of time as well as space, and we have seen already how mise-en-scene and frame mobility operate in temporal as well as spatial dimensions. What we need to consider now is how the duration of the shot affects our understanding of it.

There is a tendency to consider the shot as recording real duration. Suppose a runner takes three seconds to clear a hurdle. If we film the runner, our projected film will also consume three seconds—or so the assumption goes. One film theorist, André Bazin, made it a major tenet of his aesthetic that cinema records real time. But the relation of shot duration to the time taken by the filmed event is not so simple.

First, obviously, the duration of the event on the screen may be manipulated during filming or post-production, as we discussed earlier in this chapter. Slow-motion or fast-motion techniques may present the runner’s jump in 20 seconds or 2. Second, narrative films often permit no simple equivalence of real duration with screen duration, even within one shot. As

Chapter 3

pointed out (

p. 86

), story duration will usually differ considerably from plot duration and screen duration.

Consider a shot from Yasajiro Ozu’s

The Only Son.

It is well past midnight, and we have just seen a family awake and talking; this shot shows a dim corner of the family’s apartment, with none of the characters onscreen

(

5.197

).

But soon the light changes. The sun is rising. By the end of the shot, it is morning

(

5.198

).

This transitional shot consumes about a minute of screen time. It plainly does not record the duration of the story events; that duration would be at least five hours. To put it another way, by manipulating screen duration, the film’s plot has condensed a story duration of several hours into a minute or so.

5.197 A scene in

The Only Son

moves from night …

5.198 … to day in a single shot.

Other films use tracking movements to compress longer passages of time in a continuous shot

(

5.199

,

5.200

).

The final shot of

Signs

moves away from an autumn view through a window (itself an echo of the opening shot’s track-back from a window) and through a room, to reveal a winter landscape outside another window. Months of story time have passed during the tracking movement.

5.199 In Roger Michell’s

Notting Hill,

the protagonist’s walk through the Portobello street market moves through autumn …

5.200 … winter, and spring.

Every shot has some measurable screen duration, but in the history of cinema, directors have varied considerably in their choice of short or lengthy shots. In general, early cinema (1895–1905) tended to rely on shots of fairly long duration, since there was often only one shot in each film. With the emergence of continuity editing in the period 1905–1916, shots became shorter. In the late 1910s and early 1920s, an American film would have an average shot length of about 5 seconds. After the coming of sound, the average stretched to about 10 seconds.

Throughout the history of the cinema, some filmmakers have consistently preferred to use shots of greater duration than the average. In various countries in the mid-1930s, directors began to experiment with very lengthy shots. These filmmakers’ unusually lengthy shots—

long takes,

as they’re called—represented a powerful creative resource.

Long take

is not the same as

long shot,

which refers to the apparent distance between camera and object. As we saw in examining film production (

pp. 16

–17), a

take

is one run of the camera that records a single shot. Calling a shot of notable length a long take rather than a long shot prevents ambiguity, since the latter term refers to a distanced framing, not to shot duration. In the films of Jean Renoir, Kenji Mizoguchi, Orson Welles, Carl Dreyer, Miklós Janscó, Hou Hsiao-hsien, and Bèla Tarr, a shot may go on for several minutes. It would be impossible to analyze these films without an awareness of how the long take can contribute to form and style. One long take in Andy Warhol’s

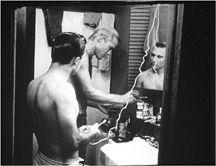

My Hustler

follows the seductive exchange of two gay men as they groom themselves in a bathroom

(

5.201

).

The shot, which runs for about 30 minutes, constitutes much of the film’s second half.

5.201 A long take in

My Hustler.

Usually, we can regard the long take as an alternative to a series of shots. The director may choose to present a scene in one or a few long takes or to present the scene through several shorter shots. When an entire scene is rendered in only one shot, the long take is known by the French term

plan-séquence,

or

sequence shot.

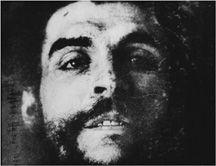

Most filmmakers use the long take selectively. One scene may rely heavily on editing, while another is presented in a long take. This permits the director to associate certain aspects of narrative or non-narrative form with the different stylistic options. A vivid instance occurs in the first part of Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino’s

Hour of the Furnaces.

Most of the film relies on editing of newsreel and staged shots to describe how European and North American ideologies penetrate developing nations. But the last shot of the film is a slow zoom-in to a photograph of the corpse of Che Guevara, symbol of guerrilla resistance to imperialism. Solanas made the shot a long take, holding it for three minutes to force the viewer to dwell on the cost of resistance

(

5.202

).

5.202 The final three-minute shot of

Hour of the Furnaces.