B0041VYHGW EBOK (193 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Neorealism created a somewhat distinctive approach to film style. By 1945, the fighting had destroyed most of Cinecittà, the large Roman studio complex, so sets were in short supply and sound equipment was rare. As a result, Neorealist miseen-scene relied on actual locales, and its photographic work tended toward the raw roughness of documentaries. Rossellini has told of buying bits of negative stock from street photographers, so that much of

Rome Open City

was shot on film with varying photographic qualities.

Shooting on the streets and in private buildings made Italian camera operators adept at cinematography that often avoided the three-point lighting system of Hollywood (4.36). Although Neorealist films often featured famous stage or film actors, nonactors were also recruited for their realistic looks and behavior. For the adult “star” of

Bicycle Thieves,

De Sica chose a factory worker: “The way he moved, the way he sat down, his gestures with those hands of a working man and not of an actor … everything about him was perfect.” The Italian cinema had a long tradition of dubbing, and the ability to postsynchronize dialogue permitted the filmmakers to work on location with smaller crews and to move the camera freely. With a degree of improvisational freedom in the acting and setting went a certain flexibility of framing, well displayed in the death of Pina in

Rome Open City

(

12.41

–

12.43

),

the final sequence of

Germany Year Zero,

and

La Terra Trema

(

12.44

).

The tracking shots through the open-air bicycle market in

Bicycle Thieves

illustrate the possibilities that the Neorealist director found in returning to location filming.

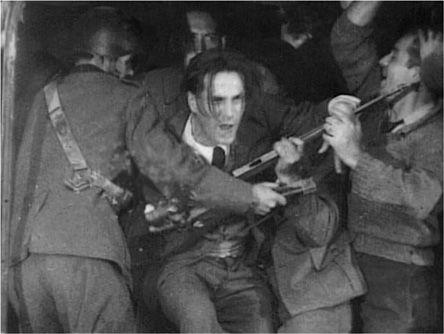

12.41 Shooting in the streets for the death of Pina in

Rome Open City

: Francesco is thrown into a truck by Nazi soldiers …

12.42 … Pina breaks through the guards …

12.43 … and a rough, bumpy shot taken from the truck shows her running after it.

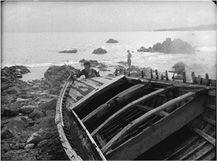

12.44 One of the magnificent landscapes in depth in

La Terra Trema.

Perhaps even more influential was the Neorealist sense of narrative form. Reacting against the intricately plotted white-telephone dramas, the Neorealists tended to loosen up narrative relations. The earliest major films of the movement, such as

Ossessione, Rome Open City,

and

Shoeshine,

contain relatively conventionally organized plots (albeit with unhappy endings). But the most formally innovative Neorealist films allow the intrusion of noncausally motivated details

(

12.45

).

Although the causes of characters’ actions are usually seen as concretely economic and political (poverty, unemployment, exploitation), the effects are often fragmentary and inconclusive. Rossellini’s

Paisan

is frankly episodic, presenting six anecdotes of life in Italy during the Allied invasion; often we are not told the outcome of an event, the consequence of a cause.

12.45 In

Bicycle Thieves,

the hero takes shelter along with a group of priests during a rain shower. The incident doesn’t affect the plot and seems as casual as any moment in daily life.

The ambiguity of Neorealist films is also a product of narration that refuses to yield an omniscient knowledge of events. The film seems to admit that the totality of reality is simply unknowable. This is especially evident in the films’ endings.

Bicycle Thieves

concludes with the worker and his son wandering down the street, their stolen bicycle still missing, their future uncertain. Although ending with the suppression of the Sicilian fishermen’s revolt against the merchants,

La Terra Trema

does not cancel the possibility that a later revolt will succeed. Neorealism’s tendency toward slice-of-life plot construction gave many films of the movement an open-ended quality quite opposed to the narrative closure of the Hollywood cinema.

As economic and cultural forces had sustained the Neorealist movement, so they helped bring it to an end. When Italy began to prosper after the war, the government looked askance at films so critical of contemporary society. After 1949, censorship and state pressures began to constrain the movement. Large-scale Italian film production began to reappear, and Neorealism no longer had the freedom of the small production company. In addition, the Neorealist directors, now famous, began to pursue more individualized concerns: Rossellini’s investigation of Christian humanism and Western history, De Sica’s sentimental romances, and Visconti’s examination of upper-class milieus. Most historians date the end of the Neorealist movement with the public attacks on De Sica’s

Umberto D

(1951). Nevertheless, Neorealist elements are still quite visible in the early works of Federico Fellini (

I. Vitelloni,

1954, is a good example) and Michelangelo Antonioni (

Cronaca di un amore,

1951); both directors had worked on Neorealist films. The movement exercised a strong influence on individual filmmakers such as Ermanno Olmi and Satyajit Ray and on groups such as the French New Wave.

“The sentiment of

[Bicycle Thieves]

is expressed overtly. The feelings invoked are a natural consequence of the themes of the story and the point of view it is told from. It is a politically committed film, fueled by a quiet but burning passion. But it never lectures. It observes rather than explains.”— Sally Potter, director,

Orlando

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw the rise of a new generation of filmmakers around the world. In country after country, there emerged directors born before World War II but grown to adulthood in the postwar era of reconstruction and rising prosperity. Japan, Canada, England, Italy, Spain, Brazil, and the United States all had their new waves or young cinema groups—some trained in film schools, many allied with specialized film magazines, most in revolt against their elders in the industry. The most influential of these groups appeared in France.

“We were all critics before beginning to make films, and I loved all kinds of cinema—the Russians, the Americans, the neorealists. It was the cinema that made us—or me, at least—want to make films. I knew nothing of life except through the cinema.”

— Jean-Luc Godard, director

In the mid-1950s, a group of young men who wrote for the Paris film journal

Cahiers du cinéma

made a habit of attacking the most artistically respected French filmmakers of the day. “I consider an adaptation of value,” wrote François Truffaut, “only when written by a

man of the cinema.

Aurenche and Bost [the leading scriptwriters of the time] are essentially literary men and I reproach them here for being contemptuous of the cinema by underestimating it.” Addressing 21 major directors, Jean-Luc Godard asserted, “Your camera movements are ugly because your subjects are bad, your casts act badly because your dialogue is worthless; in a word, you don’t know how to create cinema because you no longer even know what it is.” Truffaut and Godard, along with Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, and Jacques Rivette, also praised directors considered somewhat outdated (Jean Renoir, Max Ophuls) or eccentric (Robert Bresson, Jacques Tati).

More important, the young men saw no contradiction in rejecting the French filmmaking establishment while loving blatantly commercial Hollywood. The young rebels of

Cahiers

claimed that in the works of certain directors—certain

auteurs

(authors)—artistry existed in the American cinema. An

auteur

usually did not literally write scripts but managed nonetheless to stamp his or her personality on studio products, transcending the constraints of Hollywood’s standardized system. Howard Hawks, Otto Preminger, Samuel Fuller, Vincente Minnelli, Nicholas Ray, Alfred Hitchcock—these were more than craftsmen. Each person’s total output constituted a coherent world. Truffaut quoted Giraudoux: “There are no works, there are only auteurs.” Godard remarked later, “We won the day in having it acknowledged in principle that a film by Hitchcock, for example, is as important as a book by Aragon. Film auteurs, thanks to us, have finally entered the history of art.” And indeed, many of the Hollywood directors these critics and filmmakers championed have become recognized as great artists.

Writing criticism didn’t satisfy these young men. They itched to make movies. Borrowing money from friends and filming on location, each started to shoot short films. By 1959, they had become a force to be reckoned with. In that year, Rivette filmed

Paris nous appartient

(

Paris Belongs to Us

); Godard made

À Bout de souffle

(

Breathless

); Chabrol made his second feature,

Les Cousins;

and in April, Truffaut’s

Les Quatre cent coups

(

The 400 Blows

) won the Grand Prize at the Cannes Festival.