B0041VYHGW EBOK (197 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

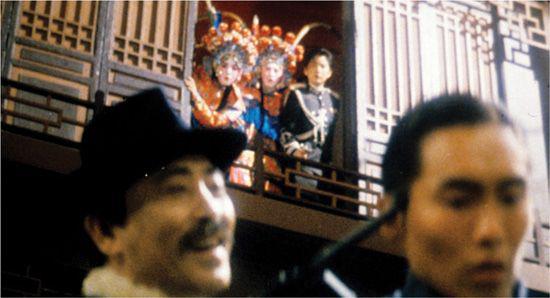

12.57 Rapid movements into and out of the frame are characteristic of Hong Kong film style. In this shot from

Peking Opera Blues,

the sheriff and his captive rise into the foreground as the three heroines watch from the rear.

Seeing the success that modern cops-and-crooks films were then enjoying, Tsui partnered with John Woo on

A Better Tomorrow

(1986), a remake of a 1960s movie

(

12.58

).

Woo was something of an in-between figure, having been a successful studio comedy director during the 1970s. With Tsui as producer,

A Better Tomorrow

became Woo’s comeback effort, one of the most successful Hong Kong films of the 1980s and a star-making vehicle for the charismatic Chow Yun-fat. Tsui, Woo, and Chow teamed again for a sequel and for the film that made Woo famous in the West,

The Killer

(1989), a lush and baroque story of the unexpected alliance between a hitman and a detective

(

12.59

).

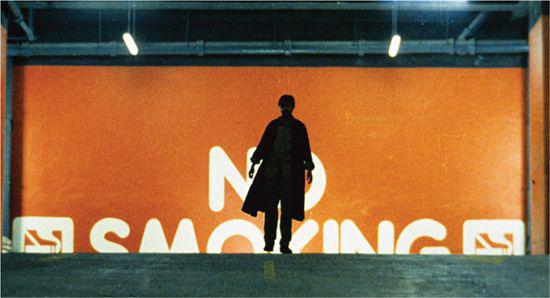

12.58 John Woo’s debt to the Western: a striking long shot as a hero walks to meet his fate in

A Better Tomorrow.

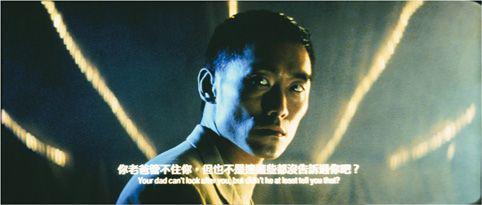

12.59 Cop and hitman as blood brothers in

The Killer.

Hong Kong cinema of the 1980s and early 1990s simmered with almost reckless energy. The rushed production schedules didn’t allow much time to prepare scripts, so the plots, borrowing freely from Chinese legend and Hollywood genres, tended to be less tightly unified than those in U.S. films. They avoided tight linkage of cause and effect in favor of a more casual, episodic construction—not, as in Italian Neorealism, to suggest the randomness of everyday life but rather to permit chases and fights to be inserted easily. While action sequences were meticulously choreographed, connecting scenes were often improvised and shot quickly. Similarly, the kung-fu films had often bounced between pathos and almost silly comedy, and this tendency to mix tones continued through the 1980s. In

A Better Tomorrow,

for example, Tsui appears in a slapstick interlude involving a cello. Again, because of rushed shooting, the plots often end abruptly, with a big action set-piece but little in the nature of a mood-setting epilogue. One of Tsui’s innovations was to provide more satisfying conclusions, as in the lilting railroad station finale of

Shanghai Blues.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Since one of David’s specialties is Hong Kong cinema, he often blogs on the subject. For a discussion of Edward Yang and Charles Wang in “Two Chinese men of the cinema,” see

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=1097

. On

Ashes of Time,

see “Ashes to Ashes (Redux),” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=3133

. For stylistic analysis of

City of Violence,

see “A glance at blows,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=3208

. On director Tsui Hark and his production work, see “Happy Birthday, Film Workshop,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=4210

.

At the level of visual style, Hong Kong directors brought the action film to a new pitch of excitement. Gunmen (and gunwomen) leaped and fired in slow motion, hovering in midair like 1970s swordfighters and kung-fu warriors. John Woo, who had been an assistant director for Chang Cheh, pushed such shots to extravagant limits. Directors also developed florid color designs, with rich reds, blues, and yellows glowing out of smoky nightclubs or narrow alleyways. Well into the 1990s, unrealistically tinted mood lighting was a trademark of Hong Kong cinema

(

12.60

).

Above all, everything was sacrificed to constant motion; even in dialogue scenes, the camera and the characters seldom stood still.

12.60 Stylized blocks of light for

The Longest Nite

(1998).

Aiming to energize the viewer, the new action directors built on the innovations of King Hu and his contemporaries. They developed a staccato cutting technique based on the tempo of martial-arts routines and Peking Opera displays, alternating rapid movement with sudden pauses. If shot composition was kept simple, an action could be cut to flow across shots very rapidly, while another cut could accentuate a moment of stillness

(

12.61

–

12.63

).

Most Hong Kong directors were unaware of the Soviet Montage movement, but in their efforts to arouse viewers kinesthetically through expressive movement and editing, they were reviving ideas of concern to 1920s filmmakers.

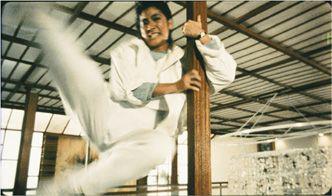

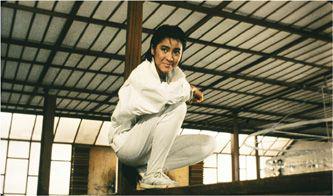

12.61 Crisp editing in

Yes, Madam!

In a shot only 7 frames long, Michele Yeoh swings swiftly …

12.62 … to knock the villain spinning (15 frames) …

12.63 … before she drops smoothly into a relaxed posture on the rail (17 frames).

The 1990s brought the golden age of Hong Kong action cinema to a close. Jackie Chan, John Woo, Chow Yun-fat, Sammo Hung, and action star Jet Li began working in Hollywood, with Yuen Wo-ping designing the action choreography for

The Matrix

(1999) and

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

(2000). A recession after Hong Kong’s 1997 handover to China depressed the local film industry. As Hollywood began imitating Hong Kong movies (as in

The Replacement Killers,

1998), local audiences developed a taste for U.S. films. At the same time, the art-cinema wing became more ambitious, and festivals rewarded the offbeat works of Wong Kar-wai (see the analysis of

Chungking Express,

pp. 417

–

422

). The action tradition was maintained by only a few directors such as Johnnie To, whose laconic film noir

The Mission

(1999) brought a leanness and pictorial abstraction to the gangster genre.

WHERE TO GO FROM HERE

Allen, Robert C., and Douglas Gomery.

Film History: Theory and Practice.

New York: Random House, 1985.

Bordwell, David.

On the History of Film Style.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Gomery, Douglas.

The Hollywood Studio System: A History.

London: BFI Publishing, 2005.

Lanzoni, Rémi Fournier.

French Cinema: From Its Beginnings to the Present.

New York: Continuum, 2002.

Luhr, William, ed.

World Cinema Since 1945.

New York: Ungar, 1987.

Salt, Barry.

Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis,

2nd ed. London: Starword, 1992.

Thompson, Kristin, and David Bordwell.

Film History: An Introduction,

3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010.

Abel, Richard,

The Ciné Goes to Town: French Cinema 1896–1914.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Allen, Robert C.

Vaudeville and Film, 1895–1915: A Study in Media Interaction.

New York: Arno, 1980.

Brewster, Ben, and Lea Jacobs.

Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Cherchi Usai, Paolo.

Silent Cinema: An Introduction.

London: British Film Institute, 2000.

Cherchi Usai, Paolo, and Lorenzo Codelli, eds.

Before Caligari: German Cinema, 1895–1920.

Pordenone: Edizioni Biblioteca dell’ Immagine, 1990.

Dibbets, Karl, and Bert Hogenkamp, eds.

Film and the First World War.

Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1995.

Elsaesser, Thomas, ed.

Early Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative.

London: British Film Institute, 1990.

Fell, John L., ed.

Film Before Griffith.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Fullerton, John, ed.

Celebrating 1895: The Centenary of Cinema.

Sydney: John Libbey, 1998.

Grieveson, Lee, and Peter Krämer, eds.

The Silent Cinema Reader.

London: Routledge, 2004.

Gunning, Tom.

D. W. Griffith and the Origins of American Narrative Film: The Early Years at Biograph.

Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

Hammond, Paul.

Marvelous Méliès.

New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1975.

Hendricks, Gordon.

The Edison Motion Picture Myth.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961.

Leyda, Jay, and Charles Musser, eds.

Before Hollywood: Turn-of-the-Century Film from American Archives.

New York: American Federation of the Arts, 1986.

Musser, Charles.

Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

———.

The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907.

New York: Scribner, 1991.

Pratt, George, ed.

Spellbound in Darkness.

Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1973.

Rossell, Deac.

Living Pictures: The Origins of the Movies.

Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998.

Tsivian, Yuri, ed.

Testimoni silenziosi: Film russi 1908–1919.

Pordenone: Edizioni Biblioteca dell’Immagine, 1989. (Bilingual in Italian and English.)

Youngblood, Denise.

The Magic Mirror: Moviemaking in Russia, 1908–1918.

Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1999.

Balio, Tino, ed.

The American Film Industry,

rev. ed. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985.

Bordwell, David, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson.

The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960.

New York: Columbia University Press, 1985.

Bowser, Eileen.

The Transformation of Cinema, 1907–1915.

New York: Scribner, 1990.

Brownlow, Kevin.

The Parade’s Gone By.

New York: Knopf, 1968.

DeBauche, Leslie Midkiff.

Reel Patriotism: The Movies and World War I.

Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997.

Gomery, Douglas.

Shared Pleasures: A History of American Moviegoing.

Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992.

Hampton, Benjamin B.

History of the American Film Industry.

1931. Reprinted. New York: Dover, 1970.

Keil, Charlie.

Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking, 1907–1918.

Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001.

Keil, Charlie, and Shelley Stamp, eds.

American Cinema’s Transitional Era: Audiences, Institutions, Practices.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Koszarski, Richard.

An Evening’s Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915–1928.

New York: Scribner, 1990.

Staiger, Janet.

Interpreting Films: Studies in the Historical Reception of American Cinema.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992.

Vasey, Ruth.

The World According to Hollywood, 1928–1939.

Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997.

Barlow, John D.

German Expressionist Film.

Boston: Twayne, 1982.

Budd, Mike, ed.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari: Texts, Contexts, Histories.

New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990.

Eisner, Lotte.

The Haunted Screen.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969.

———.

Fritz Lang.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

———.

F. W. Murnau.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Kracauer, Siegfried.

From Caligari to Hitler.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1947.

Kreimeier, Klaus.

The UFA Story: A History of Germany’s Greatest Film Company 1918–1945.

Trans. Robert and Rita Kimber. New York: Hill & Wang, 1996.

Myers, Bernard S.

The German Expressionists.

New York: Praeger, 1963.

Robinson, David.

Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari.

London: British Film Institute, 1997. (In English.)

Scheunemann, Dietrich, ed.

Expressionist Film: New Perspectives.

Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2003.

Selz, Peter.

German Expressionist Painting.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1957.

Thompson, Kristin.

Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood: German and American Film After World War I.

Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2005.

Willett, John.

Expressionism.

New York: McGraw-Hill, 1970.

———.

The New Sobriety: Art and Politics in the Weimar Republic, 1917–1933.

London: Thames & Hudson, 1978.

Abel, Richard.

French Cinema: The First Wave, 1915–1929.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984.

———.

French Film Theory and Criticism, 1907–1939,

vol. 1. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Brownlow, Kevin.

“Napoleon”: Abel Gance’s Classic Film.

New York: Knopf, 1983.

Clair, René.

Cinema Yesterday and Today.

New York: Dover, 1972.

King, Norman.

Abel Gance: A Politics of Spectacle.

London: British Film Institute, 1984.

Bordwell, David.

The Cinema of Eisenstein.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Bowlt, John, ed.

Russian Art of the Avant-Garde.

New York: Viking Press, 1973.

Carynnyk, Marco, ed.

Alexander Dovzhenko: Poet as Filmmaker.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1973.

Eisenstein, S. M.

S. M. Eisenstein: Writings 1922–1934,

Richard Taylor, ed. London: British Film Institute, 1988;

Eisenstein, Volume 2, Towards a Theory of Montage,

Michael Glenny and Richard Taylor, eds. London: British Film Institute, 1991;

Eisenstein Writings 1934–1947,

Richard Taylor, ed. London: British Film Institute, 1996.

Beyond the Stars: The Memoirs of Sergei Eisenstein,

vol. 4, Richard Taylor, ed., William Powell, trans. London: British Film Institute, 1995.

Kepley, Jr., Vance.

In the Service of the State: The Cinema of Alexander Dovzhenko.

Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1986.

———.

The End of St. Petersburg.

London: I. B. Tauris, 2003.

Kuleshov, Lev.

Kuleshov on Film.

Ed. and trans. Ronald Levaco. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974.

Leyda, Jay.

Kino,

3rd ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983.

Lodder, Christina.

Russian Constructivism.

New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1983.

Michelson, Annette, ed.

Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

Nilsen, Vladimir.

The Cinema as a Graphic Art.

New York: Hill & Wang, 1959.

Petric, Vlada.

Constructivism in Film: The Man with a Movie Camera—A Cinematic Analysis.

London: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Pudovkin, V. I.

Film Technique and Film Acting.

New York: Grove Press, 1960.

Schnitzer, Luda, Jean Schnitzer, and Marcel Martin, eds.

Cinema and Revolution.

New York: Hill & Wang, 1973.

Taylor, Richard.

The Politics of the Soviet Cinema, 1917–1929.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Taylor, Richard, and Ian Christie, eds.

The Film Factory: Russian and Soviet Cinema in Documents, 1896–1939.

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988.

———.

Inside the Film Factory: New Approaches to Russian and Soviet Cinema.

London: Routledge, 1991.

Youngblood, Denise.

Soviet Cinema in the Silent Era, 1918–1933.

Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1985.

Balio, Tino.

Grand Design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, 1930–1939.

New York: Scribner, 1993.

Balio, Tino, ed.

The American Film Industry,

rev. ed. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985.

———.

Hollywood in the Age of Television.

Boston: Unwin Hyman, 1990.

Bordwell, David, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson.

The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960.

New York: Columbia University Press, 1985.

Crafton, Donald.

The Talkies: American Cinema’s Transition to Sound 1926–1931.

New York: Scribner, 1997.

Koszarski, Richard, ed.

Hollywood Directors, 1914–1940.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Maltby, Richard.

Harmless Entertainment: Hollywood and the Ideology of Consensus.

Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1983.

———.

Hollywood Cinema,

2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 2003.

Schatz, Thomas.

Boom and Bust: American Cinema in the 1940s.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Silver, Alain, and Elizabeth Ward.

Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style.

Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 1979.

Walker, Alexander.

The Shattered Silents: How the Talkies Came to Stay.

New York: Morrow, 1979.

“Widescreen.” Issue of

Velvet Light Trap

21 (Summer 1985).

Armes, Roy.

Patterns of Realism.

New York: A. S. Barnes, 1970.

Bazin, André. “Cinema and Television.”

Sight and Sound

28, 1 (Winter 1958–59): 26–30.

———.

What Is Cinema?

vol. 2. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971.

Bondanella, Peter.

Italian Cinema from Neorealism to the Present.

New York: Ungar, 1983.

Brunette, Peter.

Roberto Rossellini.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Leprohon, Pierre.

The Italian Cinema.

New York: Praeger, 1984.

Liehm, Mira.

Passion and Defiance: Film in Italy from 1942 to the Present.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

Marcus, Millicent.

Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Overbey, David, ed.

Springtime in Italy: A Reader on Neo-Realism.

London: Talisman, 1978.

Sitney, P. Adams.

Vital Crises in Italian Cinema: Iconography, Stylistics, Politics.

Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995.

Crisp, Colin.

The Classic French Cinema, 1930–1960.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Godard, Jean-Luc.

Godard on Godard.

New York: Viking Press, 1972.

Hillier, Jim, ed.

Cahiers du Cinéma: The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985.

———.

Cahiers du Cinéma: The 1960s: New Wave, New Cinema, Reevaluating Hollywood.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986.

Insdorf, Annette.

François Truffaut.

New York: William Morrow, 1979.

McCabe, Colin.

Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at Seventy.

New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2003.

Mussman, Toby, ed.

Jean-Luc Godard.

New York: Dutton, 1968.

Neupert, Richard.

A History of the French New Wave Cinema,

2nd ed. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2007.

Sterritt, David.

The Films of Jean-Luc Godard: Seeing the Invisible.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Truffaut, François.

The Films in My Life.

Trans. Leonard Mayhew. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1978.

Andrew, Geoff.

Stranger Than Paradise: Maverick Film-Makers in Recent American Cinema.

London: Prion, 1998.