B0041VYHGW EBOK (36 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

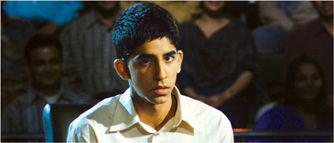

3.18 Early in

Slumdog Millionaire,

it’s established that during the quiz show Jamal recalls his past …

3.19 … most often, his glimpse of Latika at the train station.

Either sort of subjectivity may be signaled through particular film techniques. If a character is drunk, or drugged, or disoriented, the narration may render those perceptual states through slow motion, blurred imagery, or distorted sound. Similar stylistic qualities may suggest a dream or hallucination.

But some imaginary actions may not be so strongly marked. A later scene in

Slumdog Millionaire

shows Jamal reuniting with his gangster brother Salim atop a skyscraper under construction. Jamal hurls himself at Salim, and we see shots of both falling from the building

(

3.20

–

3.21

).

But the next shot presents Jamal still on the skyscraper, glaring at Salim

(

3.22

).

Now we realize that the images of the falling men were purely mental, representing Jamal’s rage. We briefly thought that their fall was really taking place because the shots lacked any marks of subjectivity.

3.20 Furious with Salim, Jamal grabs him and rushes toward the edge of the building.

3.21 Several shots present their fall.

3.22 Cut back to Jamal, glaring at Salim. The shot reveals that he only imagined killing both of them.

Typically, either perceptual or mental subjectivity is embedded in a framework of objective narration. Point-of-view shots, like those of Roger Thornhill in

North by Northwest,

and flashbacks or fantasies are bracketed by more objective shots. We are able to understand Jamal’s memory of Latika and his urge to kill Salim because those images are framed by shots of actions that we take to be really happening in the plot. Other sorts of films, however, may avoid this convention. Fellini’s

8½,

Bunuel’s

Belle de Jour,

Haneke’s

Caché,

and Nolan’s

Memento

mix objectivity and subjectivity in ambiguous ways.

Does a restricted range of knowledge create a greater subjective depth? Not necessarily.

The Big Sleep

is quite restricted in its range of knowledge, as we’ve seen. But we very seldom see or hear things from Marlowe’s perceptual vantage point, and we never get direct access to his mind.

The Big Sleep

uses almost completely objective narration. The omniscient narration of

The Birth of a Nation,

however, plunges to considerable depth with optical point-of-view shots, flashbacks, and the hero’s final fantasy vision of a world without war. Hitchcock delights in giving us greater knowledge than his characters have, but at certain moments, he confines us to their perceptual subjectivity (usually relying on point-of-view shots). Range and depth of knowledge are independent variables.

Incidentally, this is one reason why the term

point of view

is ambiguous. It can refer to range of knowledge (as when a critic speaks of an “omniscient point of view”) or to depth (as when speaking of “subjective point of view”). In the rest of this book, we will use point of view only to refer to perceptual subjectivity, as in the phrase “optical point-of-view shot,” or POV shot.

Manipulating the depth of knowledge can achieve many purposes. Plunging to the depths of mental subjectivity can increase our sympathy for a character and can cue stable expectations about what the characters will later say or do. The memory sequences in Alain Resnais’s

Hiroshima mon amour

and the fantasy sequences in Fellini’s

8½

yield information about the protagonists’ traits and possible future actions that would be less vivid if presented objectively. A subjectively motivated flashback can create parallels among characters, as does the flashback shared by mother and son in Kenji Mizoguchi’s

Sansho the Bailiff

(

3.23

–

3.26

).

A plot can create curiosity about a character’s motives and then use some degree of subjectivity—for example, inner commentary or subjective flashback—to explain the cause of the behavior. In

The Sixth Sense,

the child psychologist’s odd estrangement from his wife begins to make sense when we hear his inner recollection of something his young patient had told him much earlier.

3.23 One of the early flashbacks in

Sansho the Bailiff

starts with the mother, now living in exile with her children, kneeling by a stream.

3.24 Her image is replaced by a shot of her husband in the past, about to summon his son Zushio.

3.25 At the climax of the scene in the past, the father gives Zushio an image of the goddess of mercy and admonishes him always to show kindness to others.

3.26 Normal procedure would come out of the flashback showing the mother again, emphasizing it as her memory. Instead, we return to the present with a shot of Zushio, bearing the goddess’s image. It is as if he and his mother have shared the memory of the father’s gift.