B0041VYHGW EBOK (31 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

(Roger Thornhill has a busy day at his office.)

Rush hour hits Manhattan.

(While dictating to his secretary, Maggie, Roger leaves the office, and they take the elevator.)

Still dictating, Roger gets off the elevator with Maggie and they stride through the lobby.

The total world of the story action is sometimes called the film’s

diegesis

(the Greek word for “recounted story”). In the opening of

North by Northwest,

the traffic, streets, skyscrapers, and people we see, as well as the traffic, streets, skyscrapers, and people we assume to be offscreen, are all diegetic because they are assumed to exist in the world that the film depicts.

The term

plot

is used to describe everything visibly and audibly present in the film before us. The plot includes, first, all the story events that are directly depicted. In our

North by Northwest

example, only two story events are explicitly presented in the plot: rush hour and Roger Thornhill’s dictating to Maggie as they leave the elevator.

Note, though, that the film’s plot may contain material that is extraneous to the story world. For example, while the opening of

North by Northwest

is portraying rush hour in Manhattan, we also see the film’s credits and hear orchestral music. Neither of these elements is diegetic, since they are brought in from

outside

the story world. (The characters can’t read the credits or hear the music.) Credits and such extraneous music are thus

nondiegetic

elements. In

Chapters 6

and

7

, we’ll consider how editing and sound can function nondiegetically. At this point, we need only notice that the plot—the totality of the film—can bring in nondiegetic material.

Nondiegetic material may occur elsewhere than in credit sequences. In

The Band Wagon,

we see the premiere of a hopelessly pretentious musical play. Eager patrons file into the theater

(

3.3

),

and the camera moves closer to a poster above the door

(

3.4

).

There then appear three black-and-white images

(

3.5

–

3.7

)

accompanied by a brooding chorus. These images and sounds are clearly nondiegetic, inserted from outside the story world in order to signal that the production bombed. The plot has added material to the story for comic effect.

3.3 A hopeful investor in the play enters the theater …

3.4 … and the camera moves in on a poster predicting success for the musical.

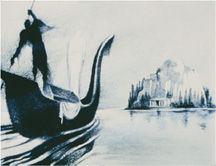

3.5 But three comic nondiegetic images reveal it to be a flop: ghostly figures on a boat …

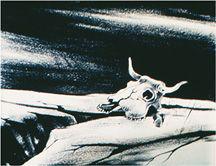

3.6 … a skull in a desert …

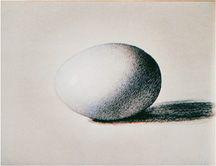

3.7 … and an egg.

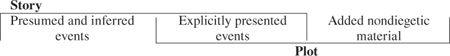

In sum, story and plot overlap in one respect and diverge in others. The plot explicitly presents certain story events, so these events are common to both domains. The story goes beyond the plot in suggesting some diegetic events that we never witness. The plot goes beyond the story world by presenting nondiegetic images and sounds that may affect our understanding of the action. A diagram of the situation would look like this:

We can think about these differences between story and plot from two perspectives. From the standpoint of the storyteller—the filmmaker—the story is the sum total of all the events in the narrative. The storyteller can present some of these events directly (that is, make them part of the plot), can hint at events that are not presented, and can simply ignore other events. For instance, though we learn later in

North by Northwest

that Roger’s mother is still close to him, we never learn what happened to his father. The filmmaker can also add nondiegetic material, as in the example from

The Band Wagon.

In a sense, then, the filmmaker makes a story into a plot.

From the perceiver’s standpoint, things look somewhat different. All we have before us is the plot—the arrangement of material in the film as it stands. We create the story in our minds on the basis of cues in the plot. We also recognize when the plot presents nondiegetic material.

The story–plot distinction suggests that if you want to give someone a synopsis of a narrative film, you can do it in two ways. You can summarize the story, starting from the very earliest incident that the plot cues you to assume or infer and running chronologically to the end. Or you can tell the plot, starting with the first incident you encountered in watching the film and presenting narrative information as you received it while watching the movie.

Our initial definition and the distinction between plot and story constitute a set of tools for analyzing how narrative works. We shall see that the story–plot distinction affects all three aspects of narrative: causality, time, and space.

If narrative depends so heavily on cause and effect, what kinds of things can function as causes in a narrative? Usually, the agents of cause and effect are

characters.

By triggering and reacting to events, characters play roles within the film’s formal system.

Most often, characters are persons, or at least entities like persons—Bugs Bunny or E.T. the extraterrestrial or even the singing teapot in

Beauty and the Beast.

For our purposes here, Michael Moore is a character in

Roger and Me

no less than Roger Thornhill is in

North by Northwest,

even though Moore is a real person and Thornhill is fictional. In any narrative film, either fictional or documentary, characters create causes and register effects. Within the film’s formal system, they make things happen and respond to events. Their actions and reactions contribute strongly to our engagement with the film.

Unlike characters in novels, film characters typically have a visible body. This is such a basic convention that we take it for granted, but it can be contested. Occasionally, a character is only a voice, as when the dead Obi-Wan Kenobi urges the Jedi master Yoda to train Luke Skywalker in

The Empire Strikes Back.

More disturbingly, in Luis Buñuel’s

That Obscure Object of Desire,

one woman is portrayed by two actresses, and the physical differences between them may suggest different sides of her character. Todd Solondz takes this innovation further in

Palindromes,

in which a 13-year-old girl is portrayed by male and female performers of different ages and races.

Along with a body, a character has

traits:

attitudes, skills, habits, tastes, psychological drives, and any other qualities that distinguish the character. Some characters, such as Mickey Mouse, may have only a few traits. When we say a character possesses several varying traits, some at odds with one another, we tend to call that character complex, or three-dimensional, or well developed. A memorable character such as Sherlock Holmes is a mass of traits. Some bear on his habits, such as his love of music or his addiction to cocaine, while others reflect his basic nature: his penetrating intelligence, his disdain for stupidity, his professional pride, his occasional gallantry.

As our love of gossip shows, we’re curious about other humans, and we bring our people-watching skills to narratives. We’re quick to assign traits to the characters onscreen, and often the movie helps us out. Most characters wear their traits far more openly than people do in real life, and the plot presents situations that swiftly reveal them to us. The opening scene of

Raiders of the Lost Ark

throws Indiana Jones’s personality into high relief. We see immediately that he’s bold and resourceful. He’s courageous, but he can feel fear. By unearthing ancient treasures for museums, he shows an admirable devotion to scientific knowledge. In a few minutes, his essential traits are presented straightforwardly, and we come to know and sympathize with him.