B0041VYHGW EBOK (14 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

The centralized studio production system has virtually disappeared. The giants of Hollywood’s golden age have become distribution companies, although they often initiate, fund, and oversee the making of films they distribute. The old studios had stars and staff under contract, so the same group of people might work together on film after film. Now each film is planned as a distinct package, with director, actors, staff, and technicians brought together for this project alone. The studio may provide its own soundstages, sets, and offices for the project, but in most cases, the producer arranges with outside firms to supply cameras, catering, locations, special effects, and anything else required.

Still, the detailed production stages remain similar to what they were in the heyday of studio production. In fact, filmmaking has become vastly more complicated in recent years, largely because of the expansion of production budgets and the growth of computer-based special effects.

Titanic

listed over 1400 names in its final credits.

Not all films using the division of labor we have outlined are big-budget projects financed by major companies. There are also low-budget

exploitation

products tailored to a particular market—in earlier decades, fringe theaters and drive-ins; now, video rentals and sales. Troma Films, maker of

The Toxic Avenger,

is probably the most famous exploitation company, turning out horror movies and teen sex comedies for $100,000 or less. Nonetheless, exploitation filmmakers usually divide the labor along studio lines. There is the producer’s role, the director’s role, and so on, and the production tasks are parceled out in ways that roughly conform to massproduction practices.

“Deep down inside, everybody in the United States has a desperate need to believe that some day, if the breaks fall their way, they can quit their jobs as claims adjusters, legal secretaries, certified public accountants, or mobsters, and go out and make their own low-budget movie. Otherwise, the future is just too bleak.”

— Joe Queenan, critic and independent filmmaker

Exploitation production often forces people to double up on jobs. Robert Rodriguez made

El Mariachi

as an exploitation film for the Spanish-language video market. The 21-year-old director also functioned as producer, scriptwriter, cinematographer, camera operator, still photographer, and sound recordist and mixer. Rodriguez’s friend Carlos Gallardo starred, coproduced, and coscripted; he also served as unit production manager and grip. Gallardo’s mother fed the cast and crew.

El Mariachi

wound up costing only about $7000.

Unlike

El Mariachi,

most exploitation films don’t enter the theatrical market, but other low-budget productions, loosely known as

independent

films, may. Independent films are made for the theatrical market but without major distributor financing. Sometimes the independent filmmaker is a well-known director, such as Spike Lee, David Cronenberg, or Joel and Ethan Cohen, who prefer to work with budgets significantly below the industry norm. The lower scale of investment allows the filmmaker more freedom in choosing stories and performers. The director usually initiates the project and partners with a producer to get it realized. Financing often comes from European television firms, with major U.S. distributors buying the rights if the project seems to have good prospects. For example, David Lynch’s low-budget

The Straight Story

was financed by French and British television before it was bought for distribution by Disney. Danny Boyle’s

Slumdog Millionaire

was made for about $15 million and nearly went straight to DVD when Warner Bros. declined to release it. Art film distributor Fox Searchlight picked it up, and it became an unexpected critical and financial success. Roughly half of

Slumdog Millionaire

was shot on 35mm. The rest was done on 2K digital cameras, which are smaller and facilitated shooting in the crowded streets of Mumbai.

As we would expect, these industry-based independents organize production in ways very close to the full-fledged studio mode. Nonetheless, because these projects require less financing, the directors can demand more control over the production process. Woody Allen, for instance, is allowed by his contract to rewrite and reshoot extensive portions of his film after he has assembled an initial cut.

The category of independent production is a roomy one, and it also includes more modest projects by less well-known filmmakers. Examples are Victor Nuñez’s

Ulee’s Gold,

Phil Morrison’s

Junebug,

and Miranda July’s

Me and You and Everyone We Know.

Even though their budgets are much smaller than for most commercial films, independent productions face many obstacles

(

1.34

).

Filmmakers may have to finance the project themselves, with the help of relatives and friendly investors; they must also find a distributor specializing in independent and low-budget films. Still, many filmmakers believe the advantages of independence outweigh the drawbacks. Independent production can treat subjects that large-scale studio production ignores. No film studios would have supported Jim Jarmusch’s

Stranger Than Paradise

or Kevin Smith’s

Clerks.

Because the independent film does not need as large an audience to repay its costs, it can be more personal and controversial. And the production process, no matter how low-budget, still relies on the basic roles and phases established by the studio tradition.

1.34 In making

Just Another Girl on the IRT,

independent director Leslie Harris used locations and available lighting in order to shoot quickly; she finished filming in just 17 days.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Studio films and independent ones aren’t always that far apart, as we suggest in “Independent film: How different?”

In large-scale and independent production, many people work on the film, each one a specialist in a particular task. But it is also possible for one person to do everything: plan the film, finance it, perform in it, run the camera, record the sound, and put it all together. Such films are seldom seen in commercial theatres, but they are central to experimental and documentary traditions.

Consider Stan Brakhage, whose films are among the most directly personal ever made. Some, such as

Window Water Baby Moving,

are lyrical studies of his home and family

(

1.35

).

Others, such as

Dog Star Man,

are mythic treatments of nature; still others, such as

23rd Psalm Branch,

are quasi-documentary studies of war and death. Funded by grants and his personal finances, Brakhage prepared, shot, and edited his films virtually unaided. While he was working in a film laboratory, he also developed and printed his footage. With over 150 films to his credit, Brakhage proved that the individual filmmaker can become an artisan, executing all the basic production tasks.

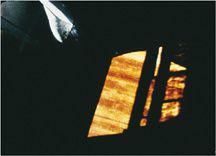

1.35 In

The Riddle of Lumen,

Stan Brakhage turned shadows and everyday objects into vivid distant pattterns.

The 16mm and digital video formats are customary for small-scale production. Financial backing often comes from the filmmaker, from grants, and perhaps from obliging friends and relatives. There is very little division of labor: the filmmaker oversees every production task and performs many of them. Although technicians or performers may help out, the creative decisions rest with the filmmaker. Experimentalist Maya Deren’s

Meshes of the Afternoon

was shot by her husband, Alexander Hammid, but she scripted, directed, and edited it and performed in the central role

(

1.36

).

Amos Poe made his lengthy, evocative experimental film

Empire II

by placing a small digital camera in a window of his Manhattan apartment and exposing single frames in bursts at intervals over an entire year

(

1.37

).

Poe edited the film himself, manipulated the images digitally, and assembled the sound track from existing songs and original music by Mader.

1.36 In

Meshes of the Afternoon,

multiple versions of the protagonist were played by the filmmaker, Maya Deren.

1.37 For

Empire II,

Amos Poe digitally manipulated this tantalizing glimpse of the Manhattan skyline, making it lyrical.

Such small-scale production is also common in documentary filmmaking. Jean Rouch, a French anthropologist, has made several films alone or with a small crew in his efforts to record the lives of marginal people living in alien cultures. Rouch wrote, directed, and photographed

Les Maîtres fous

(1955), his first widely seen film. Here he examined the ceremonies of a Ghanaian cult whose members lived a double life: most of the time they worked as low-paid laborers, but in their rituals, they passed into a frenzied trance and assumed the identities of their colonial rulers.

Similarly, Barbara Koppel devoted four years to making

Harlan County, U.S.A.,

a record of Kentucky coal miners’ struggles for union representation. After eventually obtaining funding from several foundations, she and a small crew spent 13 months living with miners during the workers’ strike. During filming, Koppel acted as sound recordist, working with cameraman Hart Perry and sometimes also a lighting person. A large crew was ruled out not only by Koppel’s budget but also by the need to fit naturally into the community. Like the miners, the filmmakers were constantly threatened with violence from strikebreakers

(

1.38

).