B0041VYHGW EBOK (10 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

The phases can overlap. Filmmakers may be scrambling for funding while shooting and assembling the film, and some assembly is usually taking place during filming. In addition, each stage modifies what went before. The idea for the film may be radically altered when the script is hammered out; the script’s presentation of the action may be drastically changed in shooting; and the material that is shot takes on new significance in the process of assembly. As the French director Robert Bresson puts it, “A film is born in my head and I kill it on paper. It is brought back to life by the actors and then killed in the camera. It is then resurrected into a third and final life in the editing room where the dismembered pieces are assembled into their finished form.”

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

In “Do filmmakers deserve the last word?” we suggest why we should always be cautious in accepting claims filmmakers offer.

These four phases include many particular jobs. Most films that we see in theaters result from dozens of specialized tasks carried out by hundreds of experts. This fine-grained division of labor has proved to be a reliable way to prepare, shoot, and assemble large-budget movies. On smaller productions, individuals perform several roles. A director might also edit the film, or the principal sound recordist on the set might also oversee the sound mixing. For

Tarnation,

a memoir of growing up in a troubled family, Jonathan Caouette assembled 19 years worth of photographs, audiotape, home movies, and videotape. Some of the footage was filmed by his parents, and some by himself as a boy. Caouette shot new scenes, edited everything on iMovie, mixed the sound, and transferred the result to digital video. In making this personal documentary, Caouette executed virtually all the phases of film production himself.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Aspiring filmmakers might want to check out our entry “The magic number 30, give or take 4.”

Two roles are central in this phase: producer and screenwriter. The tasks of the

producer

are chiefly financial and organizational. She or he may be an “independent” producer, unearthing film projects and trying to convince production companies or distributors to finance the film. Or the producer may work for a distribution company and generate ideas for films. A studio may also hire a producer to put together a particular package.

The producer nurses the project through the scriptwriting process, obtains financial support, and arranges to hire the personnel who will work on the film. During shooting and assembly, the producer usually acts as the liaison between the writer or director and the company that is financing the film. After the film is completed, the producer will often have the task of arranging the distribution, promotion, and marketing of the film and of monitoring the paying back of the money invested in the production.

A single producer may take on all these tasks, but in the contemporary American film industry, the producer’s work is further subdivided. The

executive producer

is often the person who arranged the financing for the project or obtained the literary property (although many filmmakers complain that the credit of executive producer is sometimes given to people who did little work). Once the production is under way, the

line producer

oversees the day-to-day activities of director, cast, and crew. The line producer is assisted by an

associate producer,

who acts as a liaison with laboratories or technical personnel.

The chief task of the

screenwriter

is to prepare the

screenplay

(or script). Sometimes the writer will send a screenplay to an agent, who submits it to a production company. Or an experienced screenwriter meets with a producer in a “pitch session,” where the writer can propose ideas for scripts. The first scene of Robert Altman’s

The Player

satirizes pitch sessions by showing celebrity screenwriters proposing strained ideas like “

Pretty Woman

meets

Out of Africa.

” Alternatively, sometimes the producer has an idea for a film and hires a screenwriter to develop it. This approach is common if the producer has bought the rights to a novel or play and wants to adapt it for the screen.

The screenplay goes through several stages. These include a

treatment,

a synopsis of the action; then one or more full-length scripts; and a final version, the

shooting script.

Extensive rewriting is common, and writers often must resign themselves to seeing their work recast over and over.

Shooting scripts are constantly altered, too. Some directors allow actors to modify the dialogue, and problems on location or on a set may necessitate changes in the scene. In the assembly stage, script scenes that have been shot are often condensed, rearranged, or dropped entirely.

If the producer or director finds one writer’s screenplay unsatisfactory, other writers may be hired to revise it. Most Hollywood screenwriters earn their living by rewriting other writers’ scripts. As you can imagine, this often leads to conflicts about which writer or writers deserve onscreen credit for the film. In the American film industry, these disputes are adjudicated by the Screen Writers’ Guild.

As the screenplay is being written or rewritten, the producer is planning the film’s finances. He or she has sought out a director and stars to make the package seem a promising investment. The producer must prepare a budget spelling out

above-the-line costs

(the costs of literary property, scriptwriter, director, and major cast) and

below-the-line costs

(the expenses allotted to the crew, secondary cast, the shooting and assembly phases, insurance, and publicity). The sum of aboveand below-the-line costs is called the

negative cost

(that is, the total cost of producing the film’s master negative). In 2005, the average Hollywood negative cost ran to about $60 million.

Some films don’t follow a full-blown screenplay. Documentaries, for instance, are difficult to script fully in advance. In order to get funding, however, the projects typically require a summary or an outline, and some documentarists prefer to have a written plan even if they recognize that the film will evolve in the course of filming. When making a

compilation documentary

from existing footage, the filmmakers often prepare an outline of the main points to be covered in the voice-over commentary before writing a final version of the text keyed to the image track.

“A screenplay bears somewhat the same relationship to a movie as the musical score does to a symphonic performance. There are people who can read a musical score and ‘hear’ the symphony—but no two directors will see the same images when they read a movie script. The two-dimensional patterns of colored light involved are far more complex than the onedimensional thread of sound.”

— Arthur C. Clarke, co-screenwriter,

2001: A Space Odyssey

When funding is more or less secure and the script is solid enough to start filming, the filmmakers can prepare for the physical production. In commercial filmmaking, this stage of activity is called

pre-production.

The

director,

who may have come on board the project at an earlier point, plays a central role in this and later phases. The director coordinates the staff to create the film. Although the director’s authority isn’t absolute, he or she is usually considered the person most responsible for the final look and sound of the film.

At this point, the producer and the director set up a production office, hire crew and cast the roles, and scout locations for filming. They also prepare a daily schedule for shooting. This is done with an eye on the budget. The producer assumes that the separate shots will be made out of continuity—that is, in the most convenient order for production—and put in proper order in the editing room. Since transporting equipment and personnel to a location is a major expense, producers usually prefer to shoot all the scenes taking place in one location at one time. For

Jurassic Park,

the main characters’ arrival on the island and their departure at the end of the film were both shot at the start of production, during the three weeks on location in Hawaii. A producer must also plan to shoot around actors who can’t be on the set every day. Many producers try to schedule the most difficult scenes early, before cast and crew begin to tire. For

Raging Bull,

the complex prizefight sequences were filmed first, with the dialogue scenes shot later. Keeping all such contingencies in mind, the producer comes up with a schedule that juggles cast, crew, locations, and even seasons most efficiently.

During pre-production, several things are happening at the same time under the supervision of the director and producer. A writer may be revising the screenplay while a casting supervisor is searching out actors. Because of the specialized division of labor in large-scale production, the director orchestrates the contributions of several units. He or she works with the

set unit,

or

production design unit,

headed by a

production designer.

The production designer is in charge of visualizing the film’s settings. This unit creates drawings and plans that determine the architecture and the color schemes of the sets. Under the production designer’s supervision, an

art director

oversees the construction and painting of the sets. The

set decorator,

often someone with experience in interior decoration, modifies the sets for specific filming purposes, supervising workers who find props and a

set dresser

who arranges things on the set during shooting. The

costume designer

is in charge of planning and executing the wardrobe for the production.

Working with the production designer, a

graphic artist

may be assigned to produce a

storyboard

, a series of comic strip–like sketches of the shots in each scene, including notations about costume, lighting, and camera work

(

1.24

).

Most directors do not demand a storyboard for every scene, but action sequences and shots using special effects or complicated camera work tend to be storyboarded in detail. The storyboard gives the cinematography unit and the special-effects unit a preliminary sense of what the finished shots should look like. The storyboard images may be filmed, cut together, and played with sound to help visualize the scene. This is one form of

animatics.

1.24 A page from the storyboard for Hitchcock’s

The Birds.

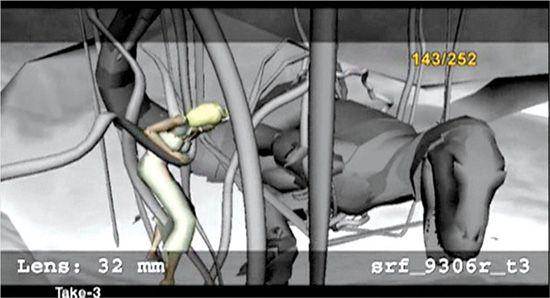

Computer graphics can take planning further. The process of

previsualization,

or “previz,” reworks the storyboards into three-dimensional animation, complete with moving figures, dialogue, sound effects, and music. Contemporary software can create settings and characters reasonably close to what will be filmed, and textures and shading can be added. Previsualization animatics are most often used to plan complicated action scenes or special effects

(

1.25

).

For

Star Wars: Episode III—Revenge of the Sith,

George Lucas’s previsualization team created 6500 detailed shots, a third of which formed the basis for shots in the finished film. In addition, previsualization helps the director test options for staging scenes, moving cameras, and timing sequences.

1.25 Animated previsualization from

King Kong.

Although the term

production

refers to the entire process of making a film, Hollywood filmmakers also use it to refer to the

shooting phase.

Shooting is also known as

principal photography.