B0041VYHGW EBOK (11 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

During shooting, the director supervises what is called the

director’s crew,

consisting of these personnel:

- The

script supervisor,

known in the classic studio era as a “script girl.” (Today one-fifth of Hollywood script supervisors are male.) The script supervisor is in charge of all details of

continuity

from shot to shot. The supervisor checks details of performers’ appearances (in the last scene, was the carnation in the left or right buttonhole?), props, lighting, movement, camera position, and the running time of each shot. - The

first assistant director (AD),

a jack-of-all-trades who, with the director, plans each day’s shooting schedule. The AD sets up each shot for the director’s approval while keeping track of the actors, monitoring safety conditions, and keeping the energy level high. - The

second assistant director,

who is the liaison among the first AD, the camera crew, and the electricians’ crew. - The

third assistant director,

who serves as messenger for director and staff. - The

dialogue coach,

who feeds performers their lines and speaks the lines of offscreen characters during shots of other performers. - The

second unit director,

who films stunts, location footage, action scenes, and the like, at a distance from where principal shooting is taking place.

The most visible group of workers is the

cast.

The cast may include

stars

—well-known players assigned to major roles and likely to attract audiences. The cast also includes

supporting players,

or performers in secondary roles;

minor players;

and

extras,

those anonymous persons who pass by in the street, come together for crowd scenes, and occupy distant desks in large office sets. One of the director’s major jobs is to shape the performances of the cast. Most directors spend a good deal of time explaining how a line or gesture should be rendered, reminding the actor of the place of this scene in the overall film, and helping the actor create a coherent performance. The first AD usually works with the extras and takes charge of arranging crowd scenes.

“If you wander unbidden onto a set, you’ll always know the AD because he or she is the one who’ll probably throw you off. That’s the AD yelling, ‘Places!’ ‘Quiet on the set!’ ‘Lunch—one-half hour!’ and ‘That’s a wrap, people!’ It’s all very ritualistic, like reveille and taps on a military base, at once grating and oddly comforting.”

— Christine Vachon, independent producer, on assistant directors

On some productions, there are still more specialized roles.

Stunt artists

will be supervised by a

stunt coordinator;

professional dancers will work with a

choreographer.

If animals join the cast, they will be handled by a

wrangler.

There have been pig wranglers (

Mad Max Beyond Thunder Dome

), snake wranglers (

Raiders of the Lost Ark

), and spider wranglers (

Arachnophobia

).

Another unit of specialized labor is the

photography unit.

The leader is the

cinematographer,

also known as the

director of photography

(or

DP

). The cinematographer is an expert on photographic processes, lighting, and camera technique. We have already seen how important Michael Mann’s two DPs, Dion Beebe and Paul Cameron, were in achieving the desired look for

Collateral

(

pp. 4

–5). The cinematographer consults with the director on how each scene will be lit and filmed

(

1.26

).

The cinematographer supervises the following:

- The

camera operator,

who runs the machine and who may also have assistants to load the camera, adjust and follow focus, push a dolly, and so on. - The

key grip,

who supervises the

grips.

These workers carry and arrange equipment, props, and elements of the setting and lighting. - The

gaffer,

the head electrician who supervises the placement and rigging of the lights.

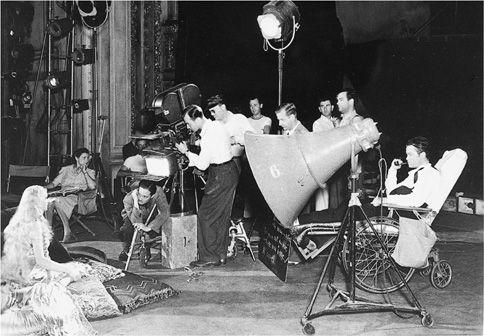

1.26 On the set of

Citizen Kane,

Orson Welles directs from his wheelchair on the far right, cinematographer Gregg Toland crouches below the camera, and actress Dorothy Comingore kneels at the left. The script supervisor is seated in the left background.

Parallel to the photography unit is the

sound unit.

This is headed by the

production recordist

(also called the

sound mixer

). The recordist’s principal responsibility is to record dialogue during shooting. Typically, the recordist uses a tape or digital recorder, several sorts of microphones, and a console to balance and combine the inputs. The recordist also tries to capture some ambient sound when no actors are speaking. These bits of room tone are later inserted to fill pauses in the dialogue. The recordist’s staff includes the following:

- The

boom operator,

who manipulates the boom microphone and conceals radio microphones on the actors. - The

third man,

who places other microphones, lays sound cables, and is in charge of controlling ambient sound.

Some productions also have a

sound designer,

who enters the process during the preparation phase and who plans a sonic style appropriate for the entire film.

A

visual-effects unit,

overseen by the

visual-effects supervisor,

is charged with preparing and executing process shots, miniatures, matte work, computer-generated graphics, and other technical shots

(

1.27

).

During the planning phase, the director and the production designer will have determined what effects are needed, and the supervisor consults with the director and the cinematographer on an ongoing basis. The visual-effects unit can number hundreds of workers, from puppetand modelmakers to specialists in digital compositing.

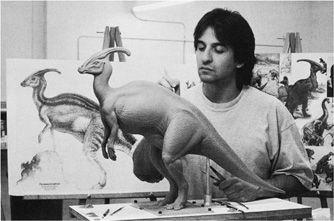

1.27 Sculpting a model dinosaur for

Jurassic Park: The Lost World.

The model was scanned into a computer for digital manipulation.

A miscellaneous unit includes a

makeup staff,

a

costume staff, hairdressers,

and

drivers

who transport cast and crew. During shooting, the producer is represented by a unit called the

producer’s crew.

Central here is the

line producer,

who manages daily organizational business, such as arranging for meals and accommodations. A

production accountant

(or

production auditor

) monitors expenditures, a

production secretary

coordinates telephone communications among units and with the producer, and

production assistants

(or

PAs

) run errands. Newcomers to the film industry often start out working as production assistants.

All this coordinated effort, involving perhaps hundreds of workers, results in many thousands of feet of exposed film and recorded sound-on-tape. For every shot called for in the script or storyboard, the director usually does several takes, or versions. For instance, if the finished film requires one shot of an actor saying a line, the director may do several takes of that speech, each time asking the actor to vary the delivery. Not all takes are printed, and only one of those becomes the shot included in the finished film. Extra footage can be used in coming-attractions trailers and electronic press kits.

Because scenes seldom are filmed in story order, the director and crew must have some way of labeling each take. As soon as the camera starts, one of the cinematographer’s staff holds up a

slate

before the lens. On the slate is written the production, scene, shot, and take. A hinged arm at the top, the clapboard, makes a sharp smack that allows the recordist to synchronize the sound track with the footage in the assembly phase

(

1.28

).

Thus every take is identified for future reference. There are also electronic slates that keep track of each take automatically and provide digital readouts.

1.28 A slate shown at the beginning of a shot in Jean-Luc Godard’s

La Chinoise.

In filming a scene, most directors and technicians follow an organized procedure. While crews set up the lighting and test the sound recording, the director rehearses the actors and instructs the cinematographer. The director then supervises the filming of a

master shot.

The master shot typically records the entire action and dialogue of the scene. There may be several takes of the master shot. Then portions of the scene are restaged and shot in closer views or from different angles. These shots are called

coverage,

and each one may require many takes. Today most directors shoot a great deal of coverage, often by using two or more cameras filming at the same time. The script supervisor checks to ensure that details are consistent within all these shots.

For most of film history, scenes were filmed with a single camera, which was moved to different points for different setups. More recently, under pressure to finish principal photography as quickly as possible, the director and the camera unit might use two or more cameras. Action scenes are often shot from several angles simultaneously because chases, crashes, and explosions are difficult to repeat for retakes. The battle scenes in

Gladiator

were filmed by 7 cameras, whereas 13 cameras were used for stunts in

XXX.

For dialogue scenes, a common tactic is to film with an A camera and a B camera, an arrangement that can capture two actors in alternating shots. The lower cost of digital video cameras has allowed some directors to experiment with shooting conversations from many angles at once, hoping to capture unexpected spontaneity in the performance. Some scenes in Lars von Trier’s

Dancer in the Dark

employed a hundred digital cameras.

When special effects are to be included, the shooting phase must carefully plan for them. In many cases, actors will be filmed against blue or green backgrounds so that their figures can be inserted into computer-created settings. Or the director may film performers with the understanding that other material will be composited into the frame

(

1.29

).

If a moving person or animal needs to be created by computer, a specialized unit will use

motion capture.

Here small sensors are attached all over the body of the subject, and as that subject moves against a blank background or a set, a special camera records the movement

(

1.30

,

1.31

).

Each sensor provides a point in a wire-frame figure on a computer. That image can then be animated and built up to a completely rendered person or animal to be inserted digitally into the film.