B0041VYHGW EBOK (12 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

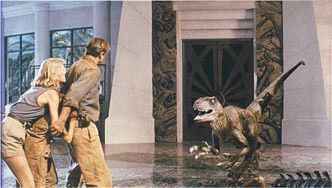

1.29 For the climax of

Jurassic Park,

the actors were shot in the set of the visitor’s center, but the velociraptors and the

Tyrannosaurus rex

were computer-generated images added later.

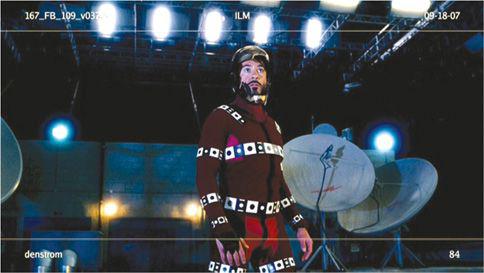

1.30 For

Iron Man,

Robert Downey Jr. performed in a motion-capture suit covered with sensors.

1.31 The same scene with computer animation partially added over his figure.

Filmmakers call the assembly phase

post-production.

(If something goes wrong, someone may promise to “fix it in post.”) Yet this phase does not begin after the shooting is finished. Rather, post-production staff members work behind the scenes throughout shooting.

Before the shooting begins, the director or producer probably hires an

editor

(also known as the

supervising editor

). This person catalogues and assembles the takes produced during shooting. The editor also works with the director to make creative decisions about how the footage can best be cut together.

Because each shot usually exists in several takes, because the film is shot out of story order, and because the master-shot/coverage approach yields so much footage, the editor’s job can be a huge one. A 100-minute feature, which amounts to about 9000 feet of 35mm film, may have been carved out of 500,000 feet of film. For this reason, postproduction on major Hollywood pictures often takes up to seven months. Sometimes several editors and assistants are brought in.

“A couple of guys in a coffee shop set out to write a gag; a couple of guys with a camera set out to film a gag; a couple of guys in an editing room set out to make sense of the trash that’s been dumped on their desks.”

— David Mamet, director,

The Spanish Prisoner

and

Redbelt

Typically, the editor receives the processed footage from the laboratory as quickly as possible. This footage is known as the

dailies

or the

rushes.

The editor inspects the dailies, leaving it to the

assistant editor

to synchronize image and sound and to sort the takes by scene. The editor meets with the director to examine the dailies, or if the production is filming far away, the editor informs the director of how the footage looks. Since retaking shots is costly and troublesome, constant checking of the dailies is important for spotting any problems with focus, exposure, framing, or other visual factors. From the dailies, the director selects the best takes, and the editor records the choices. To save money, “digital dailies” are often shown to the producer and director, but since video can conceal defects in the original footage, editors check the original shots before cutting the film.

A CLOSER LOOK

SOME TERMS AND ROLES IN FILM PRODUCTION

The rise of packaged productions, pressures from unionized workers, and other factors have led producers to credit everyone who worked on a film. Mean-while, the specialization of large-scale filmmaking has created its own jargon. Some of the most colorful terms are explained in the text. Here are some other terms that you may see in a film’s credits.

ACE:

After the name of the editor; abbreviation for the American Cinema Editors, a professional association.

ASC:

After the name of the director of photography; abbreviation for the American Society of Cinematographers, a professional association. The British equivalent is the BSC.

Additional photography:

Crew shooting footage apart from the

principal photography,

supervised by the director of photography.

Best boy:

Term from the classic studio years, originally applied to the gaffer’s assistant. Today film credits may list both a

best boy electric

and a

best boy grip

, the assistant to the key grip.

Casting director:

Member who searches for and auditions performers for the film, and suggests actors for

leading roles

(principal characters) and

character parts

(fairly standardized or stereotyped roles). She or he may also cast

extras

(background or nonspeaking roles).

Clapper boy:

Crew member who operates the clapboard (slate) that identifies each take.

Concept artist:

Designer who creates illustrations of the settings and costumes that the director has in mind for the film.

Dialogue editor:

Sound editor specializing in making sure recorded speech is audible.

Dolly grip:

Crew member who pushes the dolly that carries the camera, either from one setup to another or during a take for moving camera shots.

Foley artist:

Sound-effects specialist who creates sounds of body movement by walking or by moving materials across large trays of different substances (sand, earth, glass, and so on). Named for Jack Foley, a pioneer in postproduction sound.

Greenery man:

Crew member who chooses and maintains trees, shrubs, and grass in settings.

Lead man:

Member of set crew responsible for tracking down various props and items of decor for the set.

Loader:

Member of photography unit who loads and unloads camera magazines, as well as logging the shots taken and sending the film to the laboratory.

Matte artist:

Member of special-effects unit who paints backdrops that are then photographically or digitally incorporated into a shot in order to suggest a particular setting.

Model maker:

(1) Member of production design unit who prepares architectural models for sets to be built. (2) Member of the special-effects unit who fabricates scale models of locales, vehicles, or characters to be filmed as substitutes for full-size ones.

Property master:

Member of set crew who supervises the use of all

props,

or movable objects in the film.

Publicist, unit publicist:

Member of producer’s crew who creates promotional material regarding the production. The publicist may arrange for press and television interviews with the director and stars and for coverage of the production in the mass media.

Scenic artist:

Member of set crew responsible for painting surfaces of set.

Still photographer:

Member of crew who takes photographs of scenes and behind-the-scenes shots of cast members and others. These photographs may be used to check lighting or set design or color, and many will be used in promoting and publicizing the film.

Timer, color timer:

Laboratory worker who inspects the negative film and adjusts the printer light to achieve consistency of color across the finished product.

Video assist:

The use of a video camera mounted alongside the motion picture camera to check lighting, framing, or performances. In this way, the director and the cinematographer can try out a shot or scene on tape before committing it to film.

As the footage accumulates, the editor assembles it into a

rough cut

—the shots loosely strung in sequence, without sound effects or music. Rough cuts tend to run long—the rough cut for

Apocalypse Now

ran 7½ hours. From the rough cut, the editor, in consultation with the director, builds toward a

fine cut

or

final cut.

The unused shots constitute the

outtakes.

While the final cut is being prepared, a

second unit

may be shooting

inserts,

footage to fill in at certain places. These are typically long shots of cities or airports or close-ups of objects. At this point, titles are prepared, and further laboratory work or special-effects work may be done.

Until the mid-1980s, editors cut and spliced the

work print,

footage printed from the camera negative. In trying out their options, editors were obliged to rearrange the shots physically. Now virtually all commercial films are edited digitally. The dailies are transferred first to tape or disc, then to a hard drive. The editor enters notes on each take directly into a computer database. Such digital editing systems, usually known as

nonlinear

systems, permit random access to the entire store of footage. The editor can call up any shot, paste it alongside any other shots, trim it, or junk it. Some systems allow special effects and music to be tried out as well. Although nonlinear systems have greatly speeded up the process of cutting, the editor usually asks for a 35mm projection print of key scenes in order to check for color, details, and pacing.

As the editing team puts the footage in order, other members of the team work to manipulate the look of the shots via computer. If the footage has been shot on film, it is scanned frame by frame into computer files to create a

digital intermediate

(DI). The DI is manipulated in many ways, including changing its look through

digital color grading.

The color grader may work alone on a low-budget film or, on a larger one, supervise a group of assistants.

For special effects, filmmakers turn to computer-generated imagery (CGI). Their tasks may be as simple as deleting distracting background elements or building a crowd out of a few spectators. George Lucas has claimed that if an actor blinked at the wrong time, he would digitally erase the blink. CGI can also create imagery that would be virtually impossible with photographic film

(

1.32

).

Computers can conjure up photorealistic characters such as Gollum in

The Lord of the Rings.

(See

p. 184

–185.) Fantasy and science fiction have fostered the development of CGI, but all genres have benefited, from the comic multiplication of a single actor in

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

to the grisly realism of the digitally enhanced Omaha Beach assault in

Saving Private Ryan.

In

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,

CGI substituted for make-up, allowing Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett to plausibly portray their characters through youth to old age.