B0041VYHGW EBOK (13 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

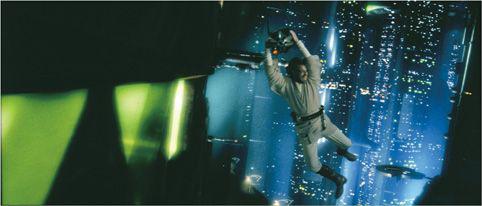

1.32 In the chase through the airways of Coruscant in

Attack of the Clones,

the actor was shot against a blue or green screen, and the backgrounds and moving vehicles were created through CGI.

Once the shots are arranged in something approaching final form, the

sound editor

takes charge of building up the sound track. The director, the composer, the picture editor, and the sound editor view the film and agree on where music and effects will be placed, a process known as

spotting.

The sound editor may have a staff whose members specialize in mixing dialogue, music, or sound effects.

Surprisingly little of the sound recorded during filming winds up in the finished movie. Often half or more of the dialogue is rerecorded in postproduction, using a process known as

automated dialogue replacement

(

ADR

). ADR usually yields better quality than location sound does. With the on-set recording serving as a

guide track,

the sound editor records actors in the studio speaking their lines (called

dubbing

or

looping

). Nonsynchronized dialogue such as the babble of a crowd (known in Hollywood as “walla”) is added by ADR as well.

Similarly, very few of the noises we hear in a film were recorded during filming. A sound editor adds sound effects, drawing on the library of stock sounds or creating particular effects for the film. Sound editors routinely manufacture footsteps, car crashes, pistol shots, and fists thudding into flesh (often produced by whacking a watermelon with an axe). In

Terminator 2,

the sound of the T-1000 cyborg passing through jail cell bars is that of dog food sliding slowly out of a can. Sound-effects technicians have sensitive hearing. One veteran noted the differences among doors: “The bathroom door has a little air as opposed to the closet door. The front door has to sound solid; you have to hear the latch sound…. Don’t just put in any door, make sure it’s right.”

Like picture editing, modern sound editing relies on computer technology. The editor can store recorded sounds in a database, classifying and rearranging them in any way desired. A sound’s qualities can be modified digitally—clipping off high or low frequencies and changing pitch, reverberation, equalization, or speed. The boom and throb of underwater action in

The Hunt for Red October

were slowed down and reprocessed from such mundane sources as a diver plunging into a swimming pool, water bubbling from a garden hose, and the hum of Disneyland’s air-conditioning plant. One technician on the film called digital sound editing “sound sculpting.”

During the spotting of the sound track, the film’s

composer

enters the assembly phase as well. The composer compiles cue sheets that list exactly where the music will go and how long it should run. The composer writes the score, although she or he will probably not orchestrate it personally. While the composer is working, the rough cut is synchronized with a

temp dub

—accompaniment pulled from recorded songs or classical pieces. Musicians record the score with the aid of a

click track,

a taped series of metronome beats synchronized with the final cut.

Dialogue, effects, and music are recorded on separate tracks, and each type of sound, however minor, will occupy a separate track. During the mixing, for each scene, the image track is run over, once for each sound, to ensure proper synchronization. The specialist who performs the task is the

rerecording mixer,

usually supervising a team of mixers. Each scene may involve dozens of tracks of individual sounds, which are all mixed together. Equalization, filtering, and other adjustment take place at this stage. The director typically oversees the final mixing session, where final adjustments to the sound result in the final mix. So many tracks are involved that the director often has the ability to change even the musical orchestration, eliminating instruments or raising the volume of certain sections of the orchestra. Once fully mixed, the master track is transferred onto 35mm soundrecording film, which encodes it as optical or digital information.

“[ADR for

Apocalypse Now

] was tremendously wearing on the actors because the entire film is looped, and of course all of the sound for everything had to be redone. So the actors were locked in a room for days and days on end shouting. Either they’re shouting over the noise of the helicopter, or they’re shouting over the noise of the boat.”— Walter Murch, sound designer

The film’s

camera negative,

which was the source of the dailies and the work print, is too precious to serve as the source for final prints. Traditionally, from the negative footage, the laboratory draws an

interpositive,

which in turn provides an

internegative.

The internegative is then assembled in accordance with the final cut, and it serves as the primary source of future prints. An alternative is to create a

digital intermediate.

Here the negative is scanned digitally, frame by frame, at high resolution. The result is then recorded back to film as an internegative. The digital intermediate allows the cinematographer to correct color, remove scratches and dust, and add special effects easily.

Once the internegative has been created, the master sound track is synchronized with it. The first positive print, complete with picture and sound, is called the

answer print.

After the director, producer, and cinematographer have approved an answer print,

release prints

are made for distribution. Using a digital intermediate makes it possible to generate additional internegatives as old ones wear out, all without any wear on the original negative or interpositive.

The work of production does not end when the final theatrical version has been assembled. In consultation with the producer and director, the postproduction staff prepares airline and broadcast television versions. For a successful film, a director’s cut or an extended edition may be released on DVD. In some cases, different versions may be prepared for different countries. Scenes in Sergio Leone’s

Once upon a Time in America

were completely rearranged for its American release. European prints of Stanley Kubrick’s

Eyes Wide Shut

featured more nudity than did American ones, in which some naked couples were blocked by digital figures added to the foreground. Once the various versions are decided upon, each is copied to a master videotape or hard drive, the source of future versions. This video transfer process often demands new judgments about color quality and sound balance.

Many fictional films have been made about the process of film production. Federico Fellini’s

8½

concerns itself with the preproduction stage of a film that is abandoned before shooting starts. François Truffaut’s

Day for Night,

David Mamet’s

State and Main,

Christopher Guest’s

For Your Consideration,

and Tom DiCillo’s

Living in Oblivion

all center on the shooting phase. The action of Brian De Palma’s

Blow Out

occurs while a low-budget thriller is in sound editing.

Singin’ in the Rain

follows a single film through the entire process, with a gigantic publicity billboard filling the final shot.

Every artist works within constraints of time, money, and opportunity. Of all the arts, filmmaking is one of the most constraining. Budgets must be maintained, deadlines must be met, weather and locations are unpredictable, and the coordination of any group of people involves unforeseeable twists and turns. Even a Hollywood blockbuster, which might seem to offer unlimited freedom, is actually confining on many levels. Big-budget filmmakers sometimes get tired of coordinating hundreds of staff and wrestling with million-dollar decisions, and they start to long for smaller projects that offer more time to reflect on what might work best.

We appreciate films more when we realize that in production, every film is a compromise made within constraints. When Mark and Michael Polish conceived their independent film

Twin Falls Idaho,

they had planned for the story to unfold in several countries. But the cost of travel and location shooting forced them to rethink the film’s plot: “We had to decide whether the film was about twins or travel.” Similarly, the involvement of a powerful director can reshape the film at the screenplay stage. In the original screenplay of

Witness,

the protagonist was Rachel, the Amish widow with whom John Book falls in love. The romance and Rachel’s confused feelings about Book formed the central plot line. But the director, Peter Weir, wanted to emphasize the clash between pacifism and violence. So William Kelley and Earl Wallace revised their screenplay to stress the mystery plot line and to center the action on Book and the introduction of urban crime into the peaceful Amish community. Given the new constraints, the screenwriters found a new form for

Witness.

Some filmmakers struggle against their constraints, pushing the limits of what’s considered doable. The production of a film we’ll study in upcoming chapters,

Citizen Kane,

was highly innovative on many fronts. Yet even this project had to accept studio routines and the limits of current technology. More commonly, a filmmaker works with the same menu of choices available to others. In directing

Collateral,

Michael Mann made creative choices about how to use digital cameras, low lighting levels, and script structure that other filmmakers working in 2004 could have made—except that Mann saw new ways of employing such techniques. His choices even led to experimentation with a new type of lighting device, the ELD panels for the cab interior. The overall result was a visual style that no other film had ever achieved, though others soon imitated it.

Everything we notice on the screen in the finished movie springs from decisions made by filmmakers during the production process. Starting our study of film art with a survey of production allows us to understand some of the possibilities offered by images and sounds. Later chapters will discuss the artistic consequences of decisions made in production—everything from storytelling strategies to techniques of staging, shooting, editing, and sound work. By choosing within production constraints, filmmakers create film form and style.

Large-Scale Production

The fine-grained division of labor we’ve been describing is characteristic of

studio

filmmaking. A studio is a company in the business of manufacturing films. The most famous studios flourished in Hollywood from the 1920s to the 1960s—Paramount, Warner Bros., Columbia, and so on. These companies owned equipment and extensive physical plants, and they retained most of their workers on long-term contracts. Each studio’s central management planned all projects, then delegated authority to individual supervisors, who in turn assembled casts and crews from the studio’s pool of workers.

Organized as efficient businesses, the studios created a tradition of carefully tracking the entire process through paper records. At the start, there were versions of the script; during shooting, reports were written about camera footage, sound recording, special-effects work, and laboratory results; in the assembly phase, there were logs of shots catalogued in editing and a variety of cue sheets for music, mixing, looping, and title layout. This sort of record keeping has remained a part of large-scale filmmaking, though now it is done mostly on computer.

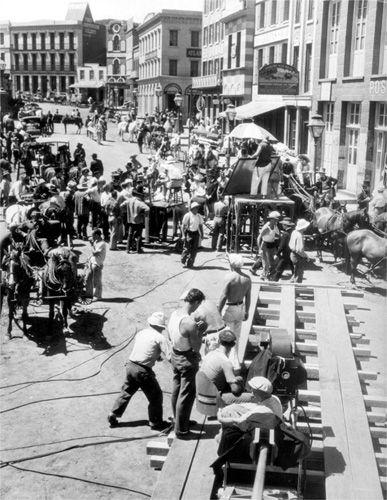

Although studio production might seem to resemble a factory’s assembly line, it was always more creative, collaborative, and chaotic than turning out cars or TV sets is. Each film is a unique product, not a replica of a prototype. In studio filmmaking, skilled specialists collaborated to create such a product while still adhering to a “blueprint” prepared by management

(

1.33

).

1.33 Studio production was characterized by a large number of highly specialized production roles. Here several units prepare a moving-camera shot for

Wells Fargo

(1937).