B0041VYHGW EBOK (45 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

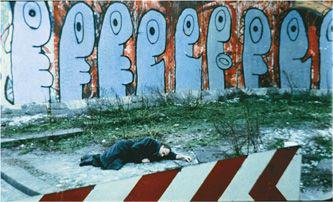

Setting can overwhelm the actors, as in Wim Wender’s

Wings of Desire

(

4.14

),

or it can be reduced to almost nothing, as in Francis Ford Coppola’s

Bram Stoker’s Dracula

(

4.15

).

4.14 In

Wings of Desire,

busy, colorful graffiti on a wall draw attention away from the man lying on the ground.

4.15 In

Bram Stoker’s Dracula,

apart from the candles, the setting of this scene has been obliterated by darkness.

The overall design of a setting can shape how we understand story action. In Louis Feuillade’s silent crime serial

The Vampires,

a criminal gang has killed a courier on his way to a bank. The gang’s confederate, Irma Vep, is also a bank employee, and just as she tells her superior that the courier has vanished, an imposter, in beard and bowler hat, strolls in behind them

(

4.16

).

They turn away from us in surprise as he comes forward

(

4.17

).

Working in a period when cutting to closer shots was rare in a French film, Feuillade draws our attention to the man by centering him in the doorway.

4.16 In

Les Vampires,

a background frame created by a large doorway …

4.17 … emphasizes the importance of an entering character.

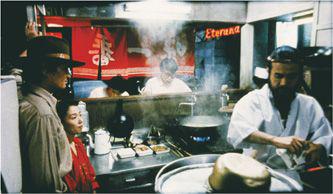

Something similar happens in a more crowded setting in Juzo Itami’s

Tampopo.

The plot revolves around a widow who is trying to improve the food and service she offers in her restaurant. In one scene, a truck driver (in a cowboy hat) helps her by taking her to another noodle shop to study technique. Itami has staged the scene so that the kitchen and the counter serve as two arenas for the action. At first, the widow watches the noodle-man take orders, sitting by her mentor on the edge of the kitchen

(

4.18

).

Quickly, the counter fills with customers calling out orders. The truck driver challenges her to match the orders with the customers, and she steps closer to the center of the kitchen

(

4.19

).

After she calls out the orders correctly, she turns her back to us, and our interest shifts to the customers at the counter, who applaud her

(

4.20

).

4.18 In

Tampopo,

at the start of the scene, the noodle counter, with only two customers, occupies the center of the action. The widow and her truck driver mentor stand inconspiciously at the left.

4.19 After the counter is full, the dramatic emphasis shifts to the kitchen when the widow rises and takes the challenge to name the customers’ orders. Her red dress helps draw attention to her.

4.20 When she has triumphantly matched the orders, she gets a round of applause. By turning her away from us, Itami once more emphasizes the counter area, now filled with customers.

As the

Tampopo

example shows, color can be an important component of settings. The dark colors of the kitchen surfaces make the widow’s red dress stand out. Robert Bresson’s

L’Argent

creates parallels among its various settings by the recurrence of drab green backgrounds and cold blue props and costumes

(

4.21

–

4.23

).

In contrast, Jacques Tati’s

Play Time

displays sharply changing color schemes. In the first portion of

Play Time,

the settings and costumes are mostly gray, brown, and black—cold, steely colors. Later in the film, however, beginning in the restaurant scene, the settings start to sport cheery reds, pinks, and greens. This change in the settings’ colors supports a narrative development that shows an inhuman city landscape that is transformed by vitality and spontaneity.

4.21 Color links the home in

L’Argent …

4.22 … to the prison …

4.23 … and later to the old woman’s home.