B0041VYHGW EBOK (67 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

The range of tonalities in the image is most crucially affected by the

exposure

of the image during filming. The filmmaker usually controls

exposure

by regulating how much light passes through the camera lens, though images shot with correct exposure can also be overexposed or underexposed in developing and printing. We commonly think that a photograph should be well exposed—neither underexposed (too dark, not enough light admitted through the lens) nor overexposed (too bright, too much light admitted through the lens). But even correct exposure usually offers some latitude for choice; it is not an absolute.

The filmmaker can manipulate exposure for specific effects. American film noir of the 1940s sometimes underexposed shadowy regions of the image in keeping with low-key lighting techniques. In

Vidas Secas,

Nelson Pereira dos Santos overexposed the windows of the prison cell to sharpen the contrast between the prisoner’s confinement and the world of freedom outside

(

5.13

).

In the Moria sequence,

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring

used overexposure in several shots. In

5.14

, the white glare was achieved by digital grading that simulated photographic overexposure.

5.13 Deliberate overexposure of windows in

Vidas Secas.

5.14 In

The Fellowship of the Ring,

the overexposure of the wizard’s staff makes the Fellowship a bright island threatened by countless orcs in the surrounding darkness.

Choices of exposure are particularly critical in working with color. For shots of

Kasba,

Kumar Shahani chose to emphasize tones within shaded areas, and so he exposed them and let sunlit areas bleach out somewhat

(

5.15

,

5.16

).

5.15 In

Kasbah,

the vibrant hues of the store’s wares stand out, while the countryside behind is overexposed …

5.16 … while at other moments underexposure for the shaded porches emphasizes the central outdoor area.

Exposure can in turn be affected by

filters

—slices of glass or gelatin put in front of the lens of the camera or printer to reduce certain frequencies of light reaching the film. Filters thus alter the range of tonalities in quite radical ways. Before modern improvements in film stocks and lighting made it practical to shoot most outdoor night scenes at night, filmmakers routinely made such scenes by using blue filters in sunlight—a technique called

day for night

(

5.17

).

Hollywood cinematographers since the 1920s have sought to add glamour to close-ups, especially of women, by means of diffusion filters and silks placed over light sources.

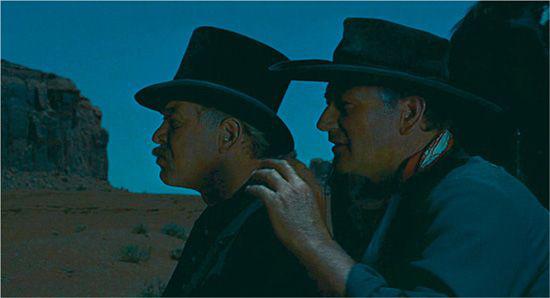

5.17 In

The Searchers,

this scene of the protagonists spying on an Indian camp from a bluff was shot in sunlight using day-for-night filters.

A gymnast’s performance seen in slow motion, ordinary action accelerated to comic speed, a tennis serve stopped in a freeze-frame—we are all familiar with the effects of the control of the speed of motion. Of course, the filmmaker who stages the event to be filmed can (within limits) dictate the pace of the action. But that pace can also be controlled by a photographic power unique to cinema: the control of the speed of movement seen on the screen.

The speed of the motion we see on the screen depends on the relation between the rate at which the film was shot and the rate of projection. Both

rates

are calculated in frames per second. The standard rate, established when synchronized-sound cinema came in at the end of the 1920s, was 24 frames per second (fps). Today’s 35mm cameras commonly offer the filmmaker a choice of anything between 8 and 64 fps, with specialized cameras offering still wider range of choice.

If the movement is to look accurate on the screen, the rate of shooting should correspond to the rate of projection. That’s why silent films sometimes look jerky today: films shot at anywhere from 16 to 20 fps are speeded up when shown at 24 fps. Projected at the correct speed, silent films can look as smooth as movies made today.

As the silent films indicate, if a film is exposed at fewer frames per second than the projection, the screen action will look speeded up. This is the

fast-motion

effect sometimes seen in comedies. But fast motion has long been used for other purposes. In F. W. Murnau’s

Nosferatu,

the vampire’s coach rushes skittishly across the landscape, suggesting his supernatural power. In Godfrey Reggio’s

Koyaanisqatsi,

delirious fast motion renders the hectic rhythms of urban life

(

5.18

).

More recent films have used fast motion to grab our attention and accelerate the pace, whisking us through a setting to the heart of the action.

5.18 Cars become blurs of light when shot in fast motion for

Koyaanisqatsi.

The more frames per second shot, the slower the screen action will appear. The resulting

slow-motion

effect is used notably in Dziga Vertov’s

Man with a Movie Camera

to render sports events in detail, a function that continues to be important today. The technique can also be used for expressive purposes. In Rouben Mamoulian’s

Love Me Tonight,

the members of a hunt decide to ride quietly home to avoid waking the sleeping deer; their ride is filmed in slow motion to create a comic depiction of noiseless movement. Today slow-motion footage often functions to suggest that the action takes place in a dream or fantasy or to convey enormous power, as in a martial-arts film. Slow-motion scenes of lovers walking add a lyrical rhythm to Wong Kar-wai’s

In the Mood for Love.

Slow motion is also used for emphasis, becoming a way of dwelling on a moment of spectacle or high drama.

To enhance expressive effects, filmmakers can change the speed of motion in the course of a shot. Often the change of speed helps create special effects. In

Die Hard

a fireball bursts up an elevator shaft toward the camera. During the filming, the fire at the bottom of the shaft was filmed at 100 fps, slowing down its progress, and then shot at faster speeds as it erupted upward, giving the impression of an explosive acceleration. For

Bram Stoker’s Dracula,

director Francis Ford Coppola wanted his vampire to glide toward his prey with supernatural suddenness. Cinematographer Michael Ballhaus used a computer program to control the shutter and the speed of filming, allowing smooth and instantaneous changes from 24 fps to 8 fps and back again.

Digital postproduction allows filmmakers to create the effect of variable shooting speeds through

ramping,

shifting speed of movement very smoothly and rapidly. In an early scene of Michael Mann’s

The Insider,

researcher Jeffrey Wigand leaves the tobacco company that has just fired him. As he crosses the lobby toward a revolving door, his brisk walk suddenly slows to a dreamlike drifting. The point of this very noticeable stylistic choice becomes apparent only in the film’s last shot. Lowell Bergman, the TV producer who has helped Wigand reveal that addictive substances are added to cigarettes, has been dismissed from CBS. Bergman strides across the lobby, and as he passes through the revolving door, his movement glides into extreme slow motion. The repetition of the technique points out the parallels between two men who have lost their livelihoods as a result of telling the truth—two insiders who have become outsiders.

Extreme forms of fast and slow motion alter the speed of the depicted material even more radically.

Time-lapse

cinematography permits us to see the sun set in seconds or a flower sprout, bud, and bloom in a minute. For this, a very low shooting speed is required—perhaps one frame per minute, hour, or even day. For

high-speed

cinematography, which may seek to record a bullet shattering glass, the camera may expose hundreds, or even thousands, of frames per second. Most cameras can be used for time-lapse shooting, but high-speed cinematography requires specially designed cameras.