B0041VYHGW EBOK (71 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

The filmmaker may also have the option of adjusting perspective while filming by

racking focus

, or

pulling focus.

A shot may begin with an object in the foreground sharply visible and the rear plane fuzzy, then rack focus so that the background elements come into crisp focus and the foreground becomes blurred. Alternatively, the focus can rack from background to foreground, as in

5.43

and

5.44

, from Bernardo Bertolucci’s

Last Tango in Paris.

5.43 In this shot from

Last Tango in Paris,

the woman, bench, and wall in the distance are in focus, while the man in the foreground is not …

5.44 … but after the camera racks focus, the man in the foreground becomes sharp and the background fuzzy.

“If I made big-budget films, I would do what the filmmakers of twenty years ago did: use 35, 40, and 50mm [lenses] with lots of light so I could have that depth of field, because it plays upon the effect of surprise. It can give you a whole series of little tricks, little hiding places, little hooks in the image where you can hang surprises, places where they can suddenly appear, just like that, within the frame itself. You can create the off-frame within the frame.”

— Benoit Jacquot, director

The image’s perspective relations may also be created by means of

special effects

. We have already seen (

p. 123

) that the filmmaker can create setting by use of models and computer-generated images. Alternatively, separately photographed planes of action may be combined on the same strip of film to create the illusion that the two planes are adjacent. The simplest way to do this is through

superimposition

. By double exposure either in the camera or in laboratory printing, one image is laid over another. Superimpositions have been used since the earliest years of the cinema. One common function is to render ghosts, which appear as translucent figures. Superimpositions also frequently provide a way of conveying dreams, visions, or memories. Typically, these mental images are shown against a close view of a face

(

5.45

).

5.45 In the opening of Quentin Tarantino’s

Kill Bill, Vol. 1,

the Bride sees the first victim of her revenge, and her memory of a violent struggle is superimposed over a tight framing of her eyes.

More complex techniques for combining strips of film to create a single shot are usually called

process

, or

composite,

shots

. These techniques can be divided into

projection process work

and

matte process work.

In projection process work, the filmmaker projects footage of a setting onto a screen, then films actors performing in front of the screen. Classical Hollywood filmmaking began this process in the late 1920s, as a way to avoid taking cast and crew on location. The Hollywood technique involved placing the actors against a translucent screen and projecting a film of the setting from behind the screen. The whole ensemble could then be filmed from the front

(

5.46

).

5.46

Boom Town.

Rear projection

, as this system was known, seldom creates very convincing depth cues. Foreground and background tend to look starkly separate, partly because of the absence of cast shadows from foreground to background and partly because all background planes tend to seem equally diffuse

(

5.47

).

5.47 In Hitchcock’s

Vertigo,

the seascape in the rear plane was shot separately and used as a back-projected setting for an embrace filmed under studio lighting.

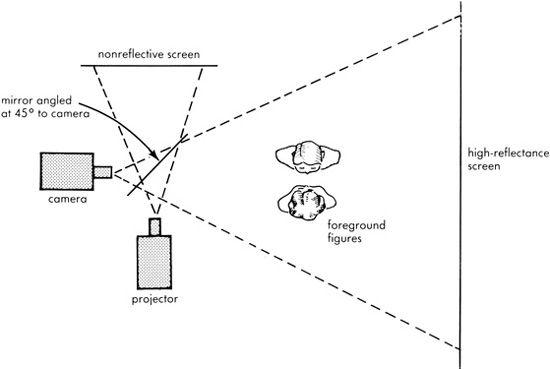

Front projection

, which came into use in the late 1960s, projects the setting onto a two-way mirror, angled to throw the image onto a high-reflectance screen. The camera photographs the actors against the screen by shooting through the mirror

(

5.48

).

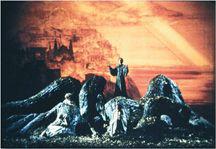

The results of front projection can be clearly seen in the “Dawn of Man” sequence of

2001: A Space Odyssey,

the first film to use front projection extensively. (At one moment, a saber-toothed tiger’s eyes glow, reflecting the projector’s light.) Because of the sharp focus of the projected footage, front projection blends foreground and background planes fairly smoothly. The nonrealistic possibilities of front projection have been explored by Hans-Jürgen Syberberg. In his film of Wagner’s opera

Parsifal,

front projection conjures up colossal, phantasmagoric landscapes

(

5.49

).

Front and rear projection have largely been replaced by digital techniques. Here action is filmed in front of a large blue or green screen rather than a film image, with the background later added by digital manipulation.

5.48 A front-projection system.

5.49 In Syberberg’s film of Wagner’s

Parsifal,

front projection conjures up colossal, phantasmagoric landscapes.

Composite filming can also be accomplished by

matte work.

A

matte

is a portion of the setting photographed on a strip of film, usually with a part of the frame empty. Through laboratory printing, the matte is joined with another strip of film containing the actors. One sort of matte involves a painting of the desired areas of setting, which is then filmed. The footage is combined with footage of action, segregated in the blank portions of the painted scenery. In this way, a matte can create an entire imaginary setting for the film. Stationary mattes of this sort have made glass shots virtually obsolete and were so widely used in commercial cinema that until the late 1990s the matte painter was a mainstay of production. In recent years, matte paintings have been made using computer programs, but they are used in the same way to create scenery

(

5.50

).

5.50 In this shot from

The Fellowship of the Ring,

the distant part of the building, the cliffs, and the sky are all on a matte painting created by computer.