B0041VYHGW EBOK (73 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

In any image, the frame is not simply a neutral border; it imposes a

certain vantage point

onto the material within the image. In cinema, the frame is important because it actively

defines

the image for us.

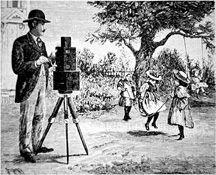

To obtain proof of the power of

framing

, we need only turn to the first major filmmaker in history, Louis Lumière. An inventor and businessman, Lumière and his brother Auguste devised one of the first practical cinema cameras

(

5.59

).

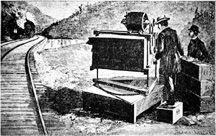

The Lumière camera, the most flexible of its day, also doubled as a projector. Whereas the bulky American camera invented by W.K.L. Dickson was about the size of an office desk

(

5.60

),

the Lumière camera weighed only 12 pounds and was small and portable. As a result of its lightness, the Lumière camera could be taken outside and could be set up quickly. Louis Lumière’s earliest films presented simple events—workers leaving his father’s factory, a game of cards, a family meal. But even at so early a stage of film history, Lumière was able to use framing to transform everyday reality into cinematic events.

5.59 The Lumière camera provided flexibility in framing.

5.60 The bulky camera of W.K.L. Dickson.

Consider one of the most famous Lumière films,

The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat

(1897). Had Lumière followed theatrical practice, he might have framed the shot by setting the camera perpendicular to the platform, letting the train enter the frame from the right side, broadside to the spectator. Instead, Lumière positioned the camera at an oblique angle. The result is a dynamic composition, with the train arriving from the distance on a diagonal

(

5.61

).

If the scene had been shot perpendicularly, we would have seen only a string of passengers’ backs climbing aboard. Here, however, Lumière’s oblique angle brings out many aspects of the passengers’ bodies and several planes of action. We see some figures in the foreground and some in the distance. Simple as it is, this single-shot film, less than a minute long, aptly illustrates how choosing a position for the camera makes a drastic difference in the framing of the image and how we perceive the filmed event.

5.61 Louis Lumière’s diagonal framing in

The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat.

Consider another Lumière short,

Baby’s Meal

(1895). Lumière selected a camera position that would emphasize certain aspects of the event. A long shot would have situated the family in its garden, but Lumière framed the figures at a medium distance, which downplays the setting but emphasizes the family’s gestures and facial expressions

(

5.62

).

The frame’s control of the scale of the event has also controlled our understanding of the event itself.

5.62

Baby’s Meal.

Framing can powerfully affect the image by means of (1) the size and shape of the frame; (2) the way the frame defines onscreen and offscreen space; (3) the way framing imposes the distance, angle, and height of a vantage point onto the image; and (4) the way framing can move in relation to the mise-en-scene.

We are so accustomed to the frame as a rectangle that we should remember that it need not be one. In painting and photography, of course, images have frames of various sizes and shapes: narrow rectangles, ovals, vertical panels, even triangles and parallelograms. In cinema, the choice has been more limited. The primary choices involve the width of the rectangular image.

The ratio of frame width to frame height is called the

aspect ratio

. The rough dimensions of the ratio were set quite early in the history of cinema by Thomas Edison, Dickson, Lumière, and other inventors. The proportions of the rectangular frame were approximately four to three, yielding an aspect ratio of 1.33:1. Nonetheless, in the silent period, some filmmakers felt that this standard was too limiting. Abel Gance shot and projected sequences of

Napoleon

(1927) in a format he called

triptychs.

This was a widescreen effect composed of three normal frames placed side by side. Gance used the effect to show a single huge expanse or to put three distinct images side by side

(

5.63

).

In contrast, the Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein argued for a square frame, which would make compositions along horizontal, vertical, and diagonal directions equally feasible.

5.63 A panoramic view from

Napoleon

joined images shot with three cameras.

The coming of sound in the late 1920s altered the frame somewhat. Adding the sound track to the filmstrip required adjusting either the shape or the size of the image. At first, some films were printed in an almost square format, usually about 1.17:1

(

5.64

).

But in the early 1930s, the Hollywood Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences established the so-called

Academy ratio

of 1.37:1, a modification of the classic 1.33:1 format to allow room for a sound track on the filmstrip

(

5.65

).

The Academy ratio was standardized throughout the world until the mid-1950s.

5.64

Public Enemy

shows the squarish aspect ratio of some early sound films.

5.65

The Rules of the Game

was shot in Academy ratio.

Since then, a variety of

widescreen

ratios has dominated 35mm filmmaking. The most common format in North America today is 1.85:1

(

5.66

).

The 1.66:1 ratio

(

5.67

)

is more frequently used in Europe than in North America. A less common ratio, also widely used in European films, is 1.75:1

(

5.68

).

This ratio is approximated by widescreen (16 × 9) television monitors and many digital-video formats.

5.66

Me and You and Everyone We Know

uses a common North American ratio.