Backstage with Julia (7 page)

Read Backstage with Julia Online

Authors: Nancy Verde Barr

In a letter Julia wrote after my first day, she acknowledged the incredible amount of work Sarah and I had accomplished, writing, "I don't see how you two did it." She should have said "how

we

did it" because she was right in there cooking and sweating with us. In fact, everyone cooked, except for Liz, who was always at the ready if we needed her. Paul did whatever we needed of him, and even Sonya helped, although her knife skills were limitedâand positively worrisome, since she was prone to gashing a finger or two. We also had two or three stagehands who willingly peeled onions, washed vegetables, trimmed herbs, and cleaned up after us. For the most part, it was the first time any of them had touched food they weren't about to eat. Later on, Julia hired another skilled assistant to help with the preparations and asked that the construction crew build a portable butcher-block work counter in the center of the room. The counter cramped our movements, but at least we had an ample work surface.

On my inaugural day of work with Julia, we left the studio at noon with the preparations for Tuesday's shows sitting on and tucked into every available space of the prep kitchen. Following Julia's instructions, we labeled everything with clearly marked Post-it notes: "DO NOT TOUCH!" The studio's night staff was notorious for hungry raids on the kitchen. My thoughts then turned to the upcoming De Gustibus demonstration and paella for three hundred in two electric woks; Julia's turned to lunch.

"Perhaps they can take us all across the street at Café des Artistes," she mused. Before we could say "roast duck and a good Chablis" we were savoring them. While the gregarious Hungarian restaurant owner, George Lang, stood by our table and talked about the current culinary scene in New York, I began inventing concerns about the De Gustibus demonstration. Had I given my friend Mary the right address? Would she remember the shrimp? Had buying the shrimp become a "pear thing" for her? Would we leave Café des Artistes in time to finish the prep for the demonstration? Julia, on the other hand, was savoring duck and trading gossip with George.

As it turned out, Mary was at the auditorium when we arrived around three o'clock, but when she handed me a plastic bag that held one small butcher-paper-wrapped package nestled in melting ice chips, I couldn't stop myself from asking, "Is that

all

the shrimp you bought?"

"That's all you asked for." God, I love people who don't worry.

The demonstration didn't exactly go off without a hitch, but the snag had nothing to do with the number of shrimp. The culprit was the sabayon dessert. While Julia attended to the twin woks, which were gurgling encouragingly with tomato saffron rice, sausage, chicken legs, and the shrimp, she asked me to make the sabayon. That meant standing in full view of the audience using a makeshift double boiler set up on a small hot plate, sitting atop a folding table and praying that I could whisk the egg yolks, sugar, and white wine into the sumptuous foam it should be and not into scrambled eggs. I had made sabayon countless times but never under such conditions. It was my first Julia-like experience in winging it.

Marshaling a positive pose and determined attitude, I spun my whisk around the bowl nonstop, like a windmill in a hurricane. Lo and behold, the ingredients uncharacteristically emulsified immediately.

Wow,

I thought, silently crediting my rather decent tennis forehand for giving me the needed arm strength. Julia looked over.

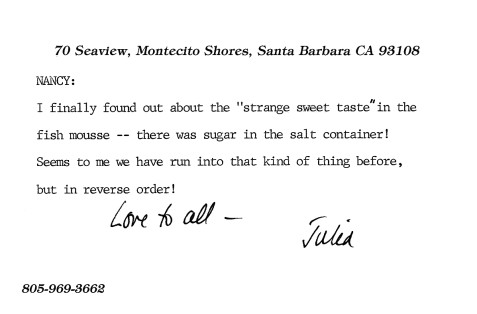

"That's amazing," she said of my record-breaking eggs-to-sabayon conversion. She stepped closer and dipped her finger into the egg foam. "It's beautiful," she said just before putting her finger in her mouth. She tasted and then, with an exaggerated grimace, boomed, "Ugh. It's salt!" In setting up for the demonstration, we had emptied all the ingredients from their original containers into several identical bowls, and I had obviously mistaken the salt for the sugar. The audience roared, and Julia gave me a conspiratorial wink as though I had staged the mistake. "You'll have to make anotherâthis time with sugar," she teasingly instructed. Never again, in all the demonstrations I did with her, did I ever put similar ingredients in unmarked bowls. One salt-for-sugar mistake is sufficient to the wise.

In the end, my second sabayon was as it should be. Let me revise that: there actually was no end. When the demonstration was over, the crowd swarmed the set to receive mouthfuls of paella, teaspoons of sabayon, autographs, and several words with Julia. It was at least ten o'clock by the time she gave her final autograph and the last vestiges of the audience left the auditorium. Then the party began. The De Gustibus owners produced several bottles of chilled champagne, and suddenly we were toasting the success of the night with several glasses of bubbly appreciation.

I distinctly recall that at the time my thoughts were running more along the lines of pillow and bed than of champagne. But the day had gone well, we were in good shape for the next morning, and Julia had arranged for me to have my own room that night near hers at the Dorset Hotel, so I didn't have to worry about getting across town on my own at that late hour. Voilà ! I indulged in the champagne, gratified that I would soon be lost in a sleep devoid of nightmares about rotten pears. I had made it through my first Julia Child workday, and I was gratified. Julia was hungry.

"Where should we go for dinner?" she asked without so much as a fleeting glance at her watch, which would have told her it was already well after ten-thirty at night.

Dinner? Who's thinking dinner?

I almost said aloud. I didn't need food; I needed rewinding.

Liz, who of course knew this was coming, was already on the phone seeking a restaurant that was still serving dinner and was near our hotel. Even Paul, ten years older than Julia and so much frailer than any of us, failed to suggest that perhaps since we had to be at the studio the next morning at five-thirty, it might be a good idea to go directly to bed.

"Doesn't Julia ever get tired?" I asked Liz.

A look of horror seized her face and she came close to slipping off her stool. "We

never

say the T-word," she warned.

The restaurant was Mercurio's, just around the corner from our hotel. It was Italian, unpretentious, and attentive without being fawning. I sat next to Paul and for the first time I had an opportunity to talk with him at some length. He fascinated me with stories of an urbane life. Of moving with his identical twin brother Charlie and his mother to Paris when he was three years old, of playing the violin and his mother singing in Parisian cafés. Of art and his own painting. Bits and pieces of his work in the diplomatic corps. He both charmed and fascinated me.

At the end of what was a copious meal, I ordered a decaffeinated espresso and Julia ordered coffee, raising her finger to emphasize that she wanted "real coffee." I felt like a wimp, having ordered decaf. The cups arrived with a plate of amaretti, and since I was in a somewhat relaxed mood thanks to the champagne and the wine at dinner, I showed Julia how to light the thin paper cookie wrappers so they floated in wisps of quickly fading color toward the ceiling. She had never seen it before, and her first several attempts at amaretti-paper arson came close to burning the tablecloth before she got the hang of it and began merrily to share her new trick with the waitstaff and several patrons.

"How do you know how to do that?" she asked me.

"I don't know. I guess it's an Italian thing."

"You're Italian?"

"Half Italian, half Irish. My maiden name is Verde."

"Verrr-de," she repeated, pronouncing it operatically, trilling the

r

in the Italian way. She had studied Italian in college and could still demand a bottle of wine

subito

while simultaneously thumping the table with her fist. "Do you teach Italian cooking classes at your school?" she asked.

My culinary training had included a smattering of Italian, but classic French cuisine was what intrigued me. Of course, I had grown up on Italian food, but it was Italian American and in my mind not worthy of study. How foolish of me!

"A few Italian classes," I responded.

"Well, you should. You have to meet Marcella Hazan. You should go to her class in Italy. I'll call her tomorrow. And you should use your full name, Nancy Verde Barr, so everyone will know you know what you're doing."

"Do you speak Italian?" Paul, who was multilingual, asked me.

"Only dialect, and most of it not suitable for company," I admitted.

"Well, I'll teach you some," he said.

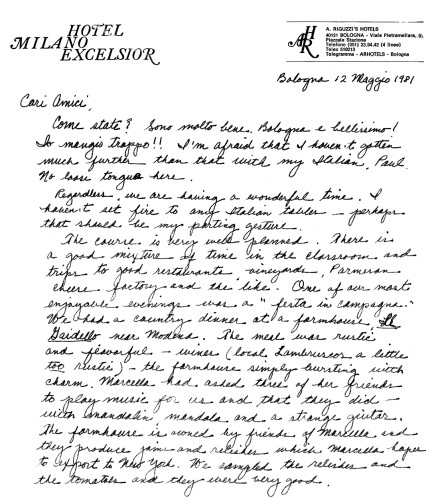

That night I began my first Italian-language lesson and professionally became Nancy Verde Barr. The next day, as promised, Julia called Marcella. A month later, with the smattering of the Italian Paul taught me, I was off to Bologna to take the first of many classes with Marcella and her husband, Victor, who expanded my knowledge and love of Italian food to the extent that it became the area of my culinary concentration. The first cookbook I published,

We Called It Macaroni,

was on Italian American food.